Hello,

DeFi lending appears vast at first glance, but it operates inefficiently beneath the surface. The same assets are spread across multiple pools, markets, and chains. As a result, a significant amount of capital remains unused, not because there are no borrowers, but because liquidity is misallocated.

This structure came from how DeFi protocols chose to manage risk. Rather than charging different borrowers based on risk levels, protocols opted to create separate markets.

While this structure improved safety, it had unintended consequences. Each market needed its own liquidity, even when the underlying asset was the same. ETH deposited in Aave’s core market could not be used to fund loans in an isolated market, even if demand was higher there. Over time, the protocol ended up with the same assets spread across multiple pools, each partially utilised.

Aave v4 aims to fix this structural inefficiency. It keeps liquidity pooled together and moves risk management to the edges of the system. Different types of borrowing still exist, but they no longer require separate pools of capital. The idea is straightforward: use the same liquidity more efficiently while keeping risk contained.

Why DeFi Lending Became Inefficient

DeFi lending protocols managed risk by separating users into different markets rather than charging them different prices.

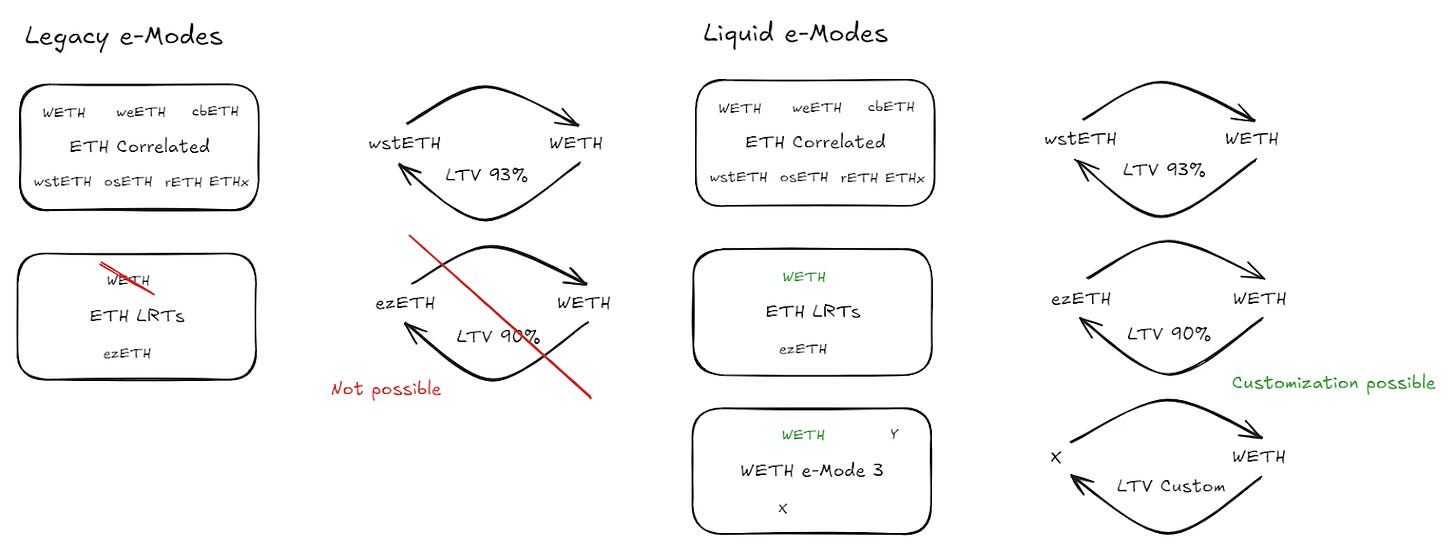

When a protocol wanted to support assets with different risk profiles, it did not adjust interest rates or collateral costs in a granular way. It created separate markets instead. Assets considered safe were grouped into one market. Newer or riskier assets were placed into isolated markets with lower limits. Higher-leverage strategies were pushed into special modes, such as E-mode. It was designed for assets that move closely together in price, such as stablecoins or liquid staking tokens. Because these assets are highly correlated, the protocol allowed users to borrow more aggressively against them.

Each market came with its own set of rules and, more importantly, its own liquidity. This made the system easier to control. If something went wrong in one market, losses stayed contained there. But it also meant liquidity could not be shared across markets, even when the underlying assets were the same.

For example, ETH supplied to Aave’s core market could only be borrowed by users operating within that market. If borrowing demand increased in an isolated market, the protocol could not automatically redirect idle ETH from the core market to meet this demand. Liquidity could only be reallocated if users manually move their funds.

As Aave expanded across assets and chains, this pattern repeated. Each new risk category required a new market, and each market required its own liquidity. This led to assets being spread thin across multiple pools, with none of them fully utilised. Though total deposits increased, the protocol’s ability to deploy capital efficiently did not keep pace.

This structure also affected pricing. Because borrowers were separated by market rather than charged differently based on risk, users inside the same market often paid similar rates regardless of how safe their collateral actually was. Risk existed, but it was expressed through access restrictions instead of prices. Safer positions indirectly subsidise riskier ones, not by design, but by limitation.

This created a large, rigid system.

Capital was available, but it was locked behind market boundaries. Supporting more assets or strategies requires more pools, more liquidity, and more fragmentation. This is exactly the problem Aave v4 is responding to.

Separating Liquidity and Risk

The core idea in Aave v4 is simple, but it required abandoning how DeFi lending had been built so far. Liquidity and risk do not need to live in the same place.

In previous versions, markets were doing two jobs at once. They were holding liquidity and enforcing risk rules. Because both things lived together, the only way to change the risk was to split the liquidity. That is what led to fragmentation. Aave v4 is trying to invert this coupling.

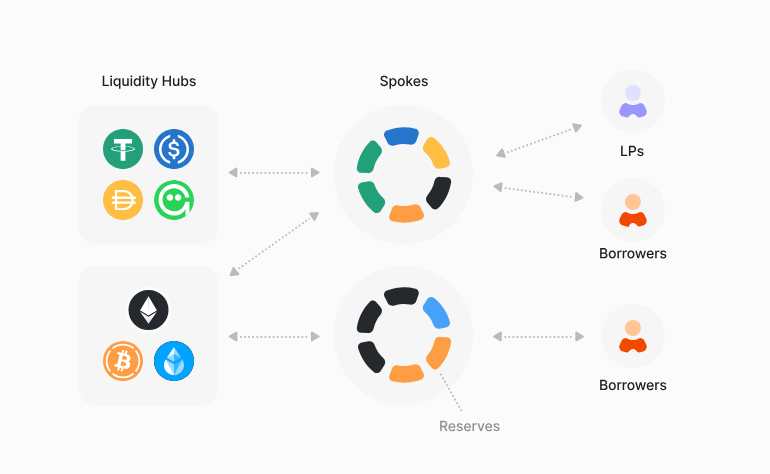

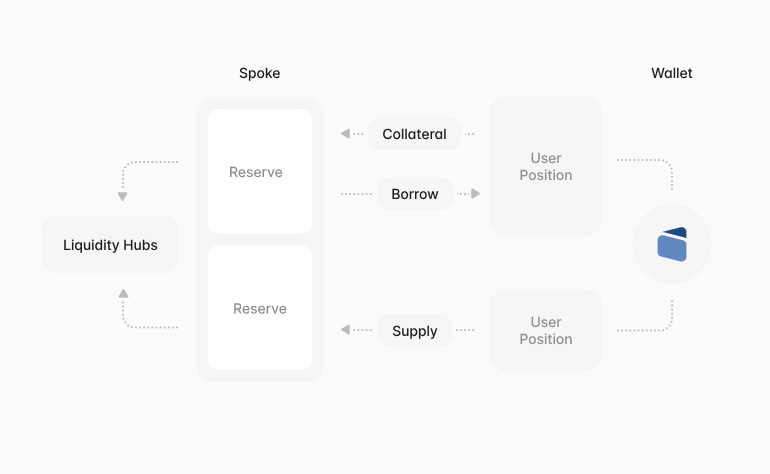

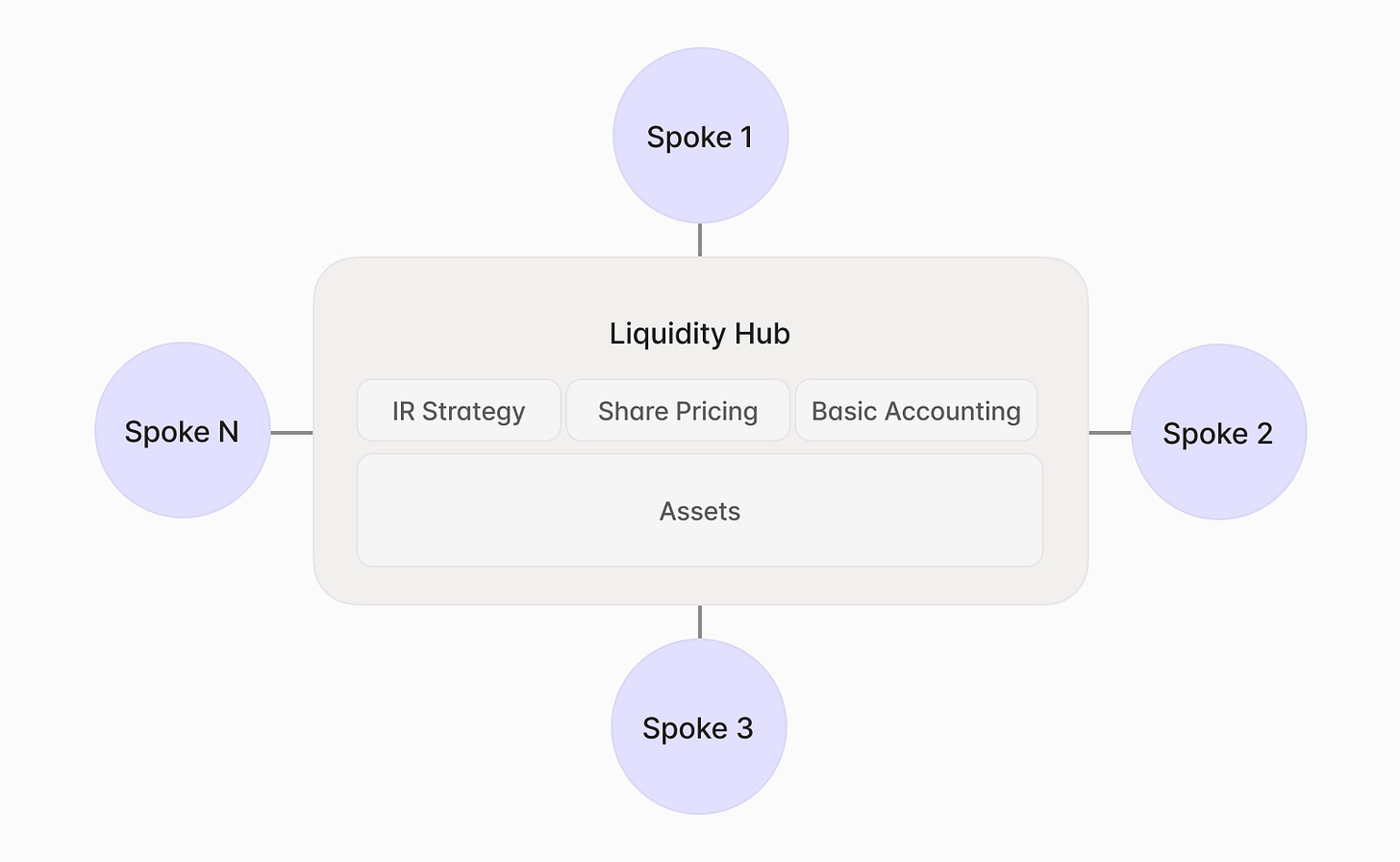

In v4, liquidity is held in a single place on each chain, called the Liquidity Hub. This Hub is not a user-facing market. It does not decide who can borrow, how much they can borrow, or against what collateral. Its job is to keep custody of assets, track supply and borrow balances, accrue interest, and ensure the system remains solvent at an aggregate level.

All user interaction happens elsewhere.

Next, instead of markets, Aave v4 introduces Spokes. A Spoke is not a pool of liquidity. It is a set of rules that determines who can access liquidity, under what conditions, and with what risk constraints. When a user borrows, they do not borrow from a Spoke. They borrow from the Hub, through a Spoke.

Because Spokes do not hold liquidity, Aave v4 no longer needs to create a new pool of capital every time it wants to support a different type of risk. All assets are consolidated into a single balance sheet. What changes from Spoke to Spoke is not where the money lives, but the rules under which that money can be used.

In earlier versions of Aave, those two things were inseparable. A market defined both the risk assumptions and the pool of funds backing them. If the protocol required stricter rules, higher leverage, or different collateral treatment, it would have to create a separate market with its own deposits. Over time, this is what caused liquidity to fragment. The only way to change the risk was to split the capital.

Aave v4 eliminates this constraint by separating accounting from access. The Hub exists solely to hold assets, track positions, and enforce system-wide solvency. It does not decide which assets are acceptable collateral, how much leverage is allowed, or which oracle is trusted. These decisions are pushed outward into Spokes. A Spoke is not a traditional market. It does not contain liquidity. It defines a borrowing context. When a user borrows through a Spoke, they are borrowing from the same underlying pool as every other user, but under specific rules. Those rules determine how collateral is valued, how much can be borrowed against it, and how quickly a position is liquidated if it becomes unsafe.

This structure enables the protocol to express very different risk profiles without duplicating capital. One Spoke can behave like today’s conservative core market. Another can impose tight caps and strict parameters on a riskier asset, or allow higher leverage for correlated assets, similar to E-Mode. All these configurations can coexist, but none requires a separate pool of funds to be pre-funded.

What keeps this from becoming dangerous is that Spokes are not allowed to draw unlimited liquidity. Each Spoke is assigned explicit limits by governance. These limits define the amount of exposure a Spoke can create and the assets it can interact with. If a Spoke starts accumulating more risk than intended, those limits can be reduced. If the risk is unacceptable, the Spoke can be disabled entirely, without touching the rest of the system or forcing users in other contexts to move their funds.

This is where capital efficiency actually improves. Liquidity is no longer parked in anticipation of a particular type of borrower or strategy. It remains available to the system as a whole and is allocated through rule sets rather than through separate pools. The protocol can support more assets and more strategies without continually splitting its balance sheet into smaller, less efficient pieces.

How Aave v4 Prices Risk

Sharing liquidity only works if a protocol can distinguish between safe and unsafe participants. In earlier versions, this distinction was mostly structural. If you wanted safer borrowing, you entered a safer market. If you wanted more leverage or used riskier collateral, you were pushed into a different pool. Pricing differences existed, but they were blunt and applied at the market level.

Aave v4 moves risk differentiation closer to the borrower rather than the market.

In v4, the interest rate for an asset still begins with a base rate determined by supply and demand in the Hub. What changes is what happens on top of that base rate. Borrowers are no longer treated as interchangeable simply because they are borrowing the same asset. The cost of borrowing now depends on how that borrowing is secured.

When a user borrows through a Spoke, the protocol evaluates the risk of that position based on the collateral used, the leverage taken, and the Spoke’s rules. If the position is considered riskier, an additional cost, known as a risk premium, is applied. Safer positions pay closer to the base rate. Riskier positions pay more. The role of Spokes here is subtle but important. They don’t just gate access to liquidity but also define how risk premiums are calculated and applied. A conservative Spoke may apply little to no premium because the positions it allows are already tightly constrained. A Spoke that allows riskier collateral or higher leverage will impose higher premiums to compensate the system for that exposure.

These premiums flow back to the shared liquidity pool. Liquidity providers are therefore compensated not only for utilisation, but for the level of risk the system is taking on. Capital is rewarded for supporting riskier activity, but only when that risk is explicitly priced.

Over time, this creates a feedback loop where, if a certain type of borrowing becomes too risky, its cost increases. If demand shifts toward safer configurations, pricing reflects that as well. The protocol does not need to create a new market to express this difference. It expresses it directly in rates. What emerges is something closer to a credit system, where borrowers are differentiated by their behaviour and collateral, not just by which market they enter. Liquidity is shared, but risk is no longer averaged out.

Unified Accounting & Liquidations

Once liquidity is shared, the obvious concern is failure modes. If everyone is borrowing from the same balance sheet, what happens when things go wrong? In earlier designs, fragmentation acted as a crude form of protection. Losses were contained because markets were isolated. The fear with unifying liquidity is that risk can spread further.

Aave v4 addresses this by changing how the protocol accounts for positions and enforces solvency.

In v3, each market effectively maintained its own accounting. Solvency was evaluated locally. Liquidations were triggered within a pool, and losses were absorbed by the pool’s liquidity. This made markets easier to reason about, but it also meant the protocol lacked a global view of how risk accumulated across the system.

In v4, accounting moves up to the Hub. The Hub maintains a single view of assets, liabilities, and interest accrual across the protocol. Every borrow, regardless of which Spoke it originates from, is recorded against the same balance sheet. This allows the protocol to reason about solvency globally rather than market by market. It always knows how much liquidity exists, how much is owed, and how much buffer remains.

When a user opens a position through a Spoke, that position is still subject to global solvency rules enforced by the Hub. If the position becomes unsafe, liquidation logic is triggered based on the rules defined by the Spoke, but settlement happens against the same underlying liquidity. The Spoke defines when and how liquidation occurs. The Hub ensures that liquidation restores the system’s solvency.

Each Spoke has explicit exposure limits. These limits cap how much risk a Spoke can introduce into the system. Even if every position in a Spoke fails simultaneously, the maximum damage is bounded. Losses cannot exceed what governance has already deemed acceptable for that Spoke. Other Spokes continue operating normally because their access to liquidity is not affected.

This represents a different failure model from earlier designs. Instead of isolating losses by isolating liquidity, v4 isolates losses by limiting exposure.

Liquidations also become more predictable. Because accounting is unified, liquidators interacte with a single liquidity source. There is no need to move assets between markets or rebalance pools mid-event. The system does not rely on users migrating capital during stress. It relies on predefined limits and consistent accounting.

This reduces the likelihood of cascading liquidations caused by liquidity shortages in specific pools. In fragmented designs, a pool could become insolvent not because the system lacked capital, but because that capital was sitting elsewhere. In v4, liquidity shortages are global signals. Unified accounting makes risk visible and bounded. The protocol always knows where losses can occur, how large they can be, and which part of the system is responsible for them. That clarity is what allows liquidity to be shared without turning stress events into protocol-wide failures.

Long-Term Unlocks

Aave v4 isn’t just a cleaner lending system. It also changes how quickly and safely new forms of risk can be introduced into DeFi.

In earlier versions, supporting something new always meant taking on structural risk. Listing a new asset, experimenting with a new collateral type, or accommodating a specialised borrower group required spinning up a new market with its own liquidity. Governance decisions were also difficult because they affected capital placement, and every experiment carried the cost of fragmentation.

In v4, experimentation becomes lighter because liquidity no longer has to move.

A new Spoke can be introduced without asking users to deposit funds into a new pool. Governance can define rules, limits, and pricing for a specific use case while keeping the balance sheet intact. If the experiment works, limits can be increased. If it does not, the Spoke can be constrained or turned off without disrupting the rest of the system.

Rather than debating whether an asset “deserves” a full market, governance can treat new assets and strategies as bounded exposures. The question shifts from should we create a market to how much risk are we willing to allocate. That is a much more precise decision, and one that can be adjusted incrementally. This is particularly important for real-world assets and institutional use cases.

RWAs often come with constraints that do not fit neatly into existing markets, like permissioning, legal wrappers, slower liquidation processes, or non-standard collateral behaviour. In previous designs, accommodating these differences required either compromising the core market or fully isolating liquidity. In v4, these constraints can live inside a Spoke, with strict limits and customised rules, while still drawing from shared liquidity.

In earlier versions, changing risk assumptions often required migrating markets or coordinating liquidity shifts. In v4, governance operates at the level of limits and rules. Adjustments can be made gradually, and risk can be dialled up or down without forcing users to act. This reduces governance overhead and lowers the cost of being wrong.

Over time, this leads to a different growth pattern for Aave as a protocol.

Aave no longer scales by launching more markets and attracting isolated liquidity. It scales by increasing the number of ways its balance sheet can be used. Capital efficiency improves because liquidity no longer needs to be pre-allocated to specific markets and left idle when demand shifts elsewhere.

What emerges is a DeFi protocol that behaves more like a financial system.

That was all for today. See you next Sunday.

Until then, stay curious!

Vaidik

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.