I’ve wanted to slowly engage with The Bitcoin Standard for a while—by reading it from cover to cover and seeing how it affects my thinking. It looms in the background of many Bitcoin discussions, often cited as a foundational text. People will say “as Saifedean explains…” and then you realise their entire reference is based on a meme or a screenshot of the cover.

So, for this month’s Monday experiment, I’m reading the book properly, in three parts. This is part one.

We’re still in the early chapters, before the full “fiat ruined everything from architecture to waistlines” rant kicks in. At this point, Saifedean Ammous is laying the groundwork, trying to convince you that money is a technology, that some forms of it are “harder” than others, and that history is essentially a process of sorting in favour of the harder options. If he can get you to internalise that, Bitcoin will later appear as “the hardest money yet,” and it will feel inevitable.

I’m not fully convinced, but I have to admit, it’s a sticky framing.

The book starts by stripping money down to something very unromantic. Not “social contract”, not “creature of the state”, just a tool for moving value through time and space without thinking too much about it every day.

Ammous keeps returning to the concept of salability. A good money-like asset is one that can be sold easily, whenever you want, without a massive loss. For it to be salable, it must function in three ways: across space—so you can take it anywhere and exchange it for what you need; across time—so it doesn’t rot or collapse in value; and across scale—so it can be used it for anything from a cup of tea to a house without needing a calculator or a bag of change.

Then, comes the word that really does all the heavy lifting in this book: hardness. Hard money is money whose supply is hard to increase. Soft money is easy to print. That’s the essence. The core intuition is simple: why would you store your life’s work in something that can be created cheaply by others?

You can feel the Austrian economic influence in every sentence, but once you strip away the ideology, the book leaves you with one very useful question: If I hold my savings in X, how easy is it for someone else to make more X?

Once you look at your own life through that lens — rupees, dollars, stables, BTC, whatever the mix is for you — it’s hard to unsee.

After setting this framework, the book walks you through a small museum of broken monies.

The first exhibit is Yap Island and its Rai stones. These are giant circular limestone disks, some weighing up to four tonnes, quarried on other islands and brought to Yap at massive effort. Ammous writes that for centuries this worked surprisingly well. The stones were too big to move or steal. Everyone in the village knew who owned which stone. Payments were made by announcing the change of ownership to the community. The stones “had salability across space” because they were recognised anywhere on the island; they had salability across time because getting new stones was so costly that the existing stock “was always far larger than whatever new supply could be produced at a given period of time… Rai stones had a very high stock-to-flow ratio.”

Then, technology shows up.

In 1871, an Irish-American captain named David O’Keefe got shipwrecked on Yap. He recovers, leaves, comes back with a large boat and explosives, and realises he can quarry Rai stones in bulk with modern tools. The villagers are split. The chief bans his stones as “too easy” and insists only the traditional ones count. Others disagree and start working for the new rocks. Conflict follows. The monetary role of the stones slowly dies. Today they’re mostly ceremonial.

It’s a neat, maybe too neat, parable. But it makes the point: once a money good loses its hardness (once someone can produce a lot of it cheaply), those who saved in it end up subsidising newcomers.

The pattern repeats with beads and shells. West African aggry beads held value because they were scarce and labour-intensive to make. Then European traders began importing them in bulk from glass factories. Ammous describes how this “slowly but surely” transformed them “from hard money to easy money, destroying their salability and causing the erosion of the purchasing power of these beads over time in the hands of the Africans who owned them, impoverishing them by transferring their wealth to the Europeans, who could now acquire the beads easily.”

Seashells and wampum go through a similar arc. They start as hard money which is scarce, hard to find, with a high stock-to-flow ratio. Then industrial boats arrive, “their supply was very highly inflated, leading to a drop in their value and a loss of salability across time,” and by 1661 they’ve lost legal-tender status.

You get variations with cattle and salt and tally sticks and cigarettes in prisoner-of-war camps. Each story is doing the same thing. Training your gut to feel that if the flow of new units can suddenly ramp up cheaply, the stock held by savers is basically a donation.

You can criticise the history for being too tidy. There’s very little about violence, politics or culture in these vignettes. Everyone behaves like a rational homo economicus with a good memory. But as a way to make you suspicious of easy-to-print money, it’s effective.

Once you’re fully traumatised by shells and beads, metals enter the picture as the grown-up solution.

Metals solve many of the salability problems. They don’t rot like grain. They’re more portable than stone monoliths. They can be minted into uniform coins, which makes pricing and accounting easier. Over time, gold and silver win the competition because they are the hardest to inflate. Annual mining adds only a small percentage to the existing stock, so no individual miner can devalue everyone’s savings.

With that, you get the long age of metal money, and then gold-backed paper. The book doesn’t linger too much on the details here. Its goal is to make you feel that once humanity stumbles into gold, it has found something close to the optimum: portable, durable, divisible, and, most importantly, expensive to create.

You can see how this sets up Bitcoin later. If your brain fully buys into “gold was the best we could do given physics and metallurgy,” then “Bitcoin is digital gold with better hardness properties” feels like a natural sequel.

What’s interesting for me in this early section is that gold comes off less as a mystical object and more as a hack around physical constraints. If you think of ancient societies as constantly trying to answer the question “how do we store the output of a good harvest or a successful voyage in a form that will survive into the future”, gold is a relatively elegant, albeit imperfect, answer.

That framing also benefits Bitcoin. It stops being “magic internet rock” and becomes “the next attempt to solve the same problems with new tools.”

We’re not there yet in the book, but you can feel the runway being built.

Then, government money enters the scene, the villain.

Up until now, the collapse of money has come from external forces. New tech shows up, breaks hardness, ruins savers. Now the culprit is internal. States and central banks, with the legal right to print money unbacked by any scarce commodity.

Fiat, in this telling, is what you get when governments realise they can separate the symbol from the backing entirely. You keep the unit, scrap the restraint. You tell people their notes are worth something because the law says so, and because taxes must be paid in them, not because they’re backed by anything hard.

Under a gold or silver standard, you can devalue or debase the currency, but you can’t experience Zimbabwe-style collapses, where salaries turn into confetti within months. Under fiat, you can. And some governments do, over and over.

Ammous spends a chunk of time explaining the societal consequences of this. Production gets cannibalised as people sell off capital just to survive. Long-term contracts break down because no one trusts the unit. Political extremism feeds off the anger and chaos. Weimar Germany is the archetype. Monetary breakdown as a prelude to something worse.

It’s not wrong that most fiat currencies have drifted down against real goods over long horizons. That’s kind of the design.

Where I start arguing with the book in my head is not on the facts, but on the framing. Fiat becomes his explanation for pretty much every modern sickness. Central banking is painted almost entirely as a device for stealth-taxing savers and subsidising borrowers. Any benefit from having a flexible lender of last resort is waved away with “but they’ll abuse it,” which, yes, is partly true, and also not the only question societies have to answer.

You don’t have to love central banks to think that “the entire twentieth century was a mistake from the moment we left full metal standards” is a bit too much.

What stuck with me

So, what did this first section actually do for me, beyond adding more maxi quotes to recognise on the timeline?

Oddly, it didn’t make me more certain about Bitcoin. It just clarified a question I wasn’t asking carefully enough.

I don’t often think about my money in the way Ammous frames it. I think about risk, and return. I think about volatility. I think about how much of my life I want to park in crypto versus boring things. I don’t systematically sit down and map who can print how much of each unit I touch, and under what rules.

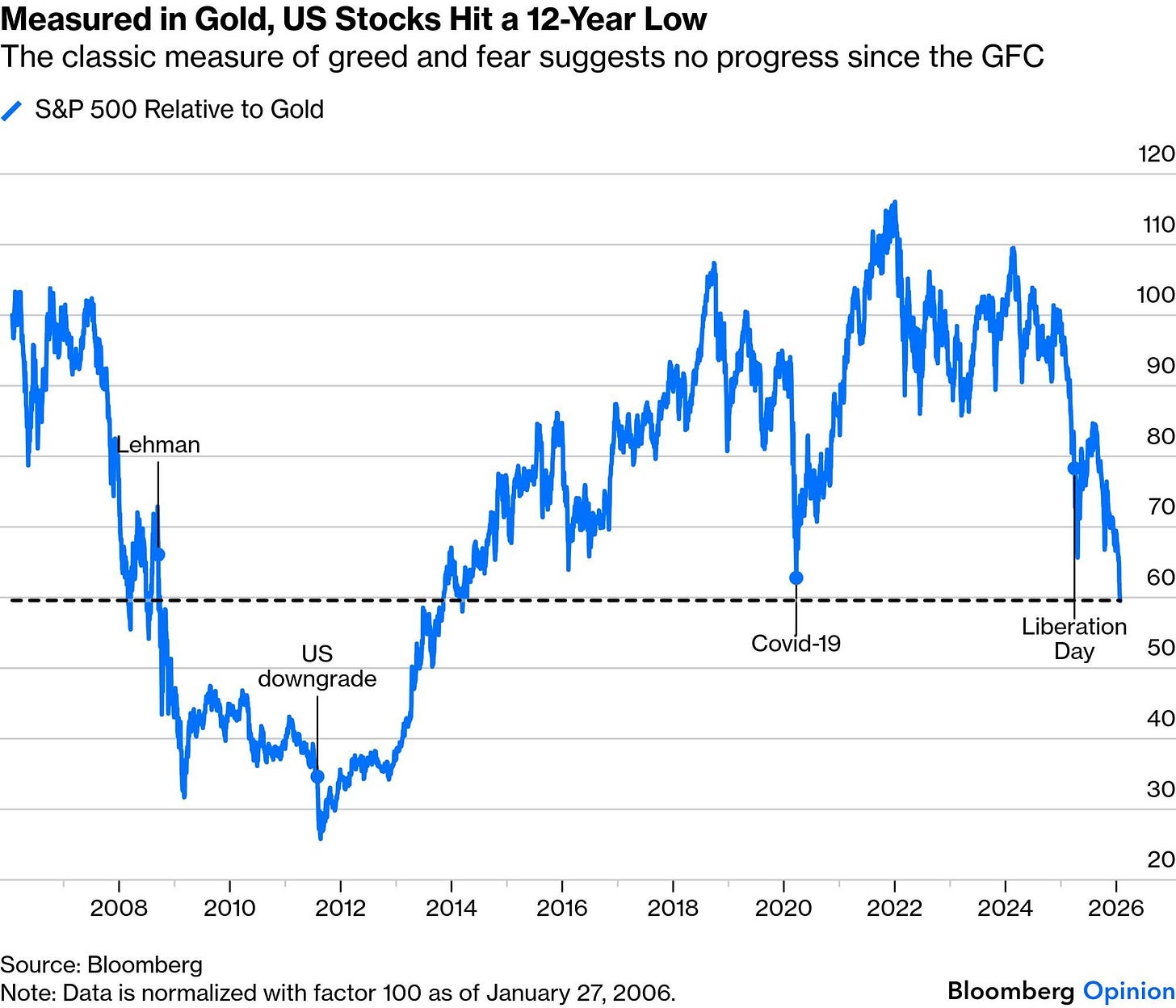

Then I saw a Bloomberg chart that plots the S&P 500 relative to gold instead of in dollars. It’s rude. In gold terms, U.S. stocks are back near levels last seen more than a decade ago, around the post-GFC era. All those dollar ATHs, all the post-Covid euphoria, collapse into a noisy bump on a flat line.

Once you see that, it’s hard to unsee the simple thing Ammous keeps banging on about. Performance is always “performance in what?”. If your base unit is slwoly debasing, your index can hit record highs, and you could still be treading water in harder terms.

I’m aware of how much the book leaves out. There’s almost no serious discussion of credit as a social tool, or of the fact that states don’t just ruin money. They also create the legal and military environment that lets markets scale in the first place. There’s no grappling with the idea that some communities might trade a bit of hardness for more room to respond to shocks. Everything is funneled through one axis: did the saver get diluted?

Maybe that’s the point. It’s a polemic, not a textbook. But I don’t want to pretend it’s the whole story.

For now, I’m happy to use it as a lens, not a religion. When I see a central bank balance sheet, or a new L2 issuance schedule, or some “stable yield” product promising 18% on dollars, I hear a small Saifedean voice asking: how hard is this money, really. And how many O’Keefes with explosives are already in the water?

For now, I’m walking away with one thought: money stores our future choices. Be picky about the unit, and wary of anyone who can print more of it than you can earn.

See you next week. Until then, keep reading.

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.

Really apreciate the honest take on not treating this as scripture. That S&P500 vs gold chart is the kinda reality check people skip when celebrating ATHs. I've been thinking about units more since noticing how stable my rent feels in coffee terms but wild in crypto terms.