Hello,

Last week, we were still in the “museum tour” part of The Bitcoin Standard. Rai stones, shells, gold, and governments finding the print button. It was mostly about what money had been and who got wrecked when the supply suddenly became cheap.

The section I’m reading now feels different. It’s less about history and more about what your money does to your brain.

Saifedean’s main point in this middle part is that the money under your feet quietly messes with your sense of time.

If the thing you save holds its value, it’s easier to think in decades. If it leaks, you’re constantly nudged back toward the next few months. From there, he stretches that story into everything else—savings, investment, interest rates, and even your relationship with the state.

You don’t have to buy into every leap to feel its shape. And I’ll be honest, some of it hit harder than I expected.

Your money is a time machine

He keeps coming back to time preference, a term that might sound like something from an economics textbook, but it’s actually one of the most useful mental models I have encountered in a while.

Some people are okay waiting. They save, invest, and defer gratification. Others want everything now. We usually file this under “self-control,” “culture,” or “whether your parents made you do chores.”

Saifadean takes it more literally and thinks that if money behaves like decent storage technology (if a dollar saved today buys roughly a dollar’s worth of stuff in ten years), patience becomes less about heroics. It becomes the default, the rational thing to do. But if your money keeps slipping away, patience starts to look like a bad trade.

Here’s where it stopped being abstract for me. I’m going to throw a lot of numbers at you here.

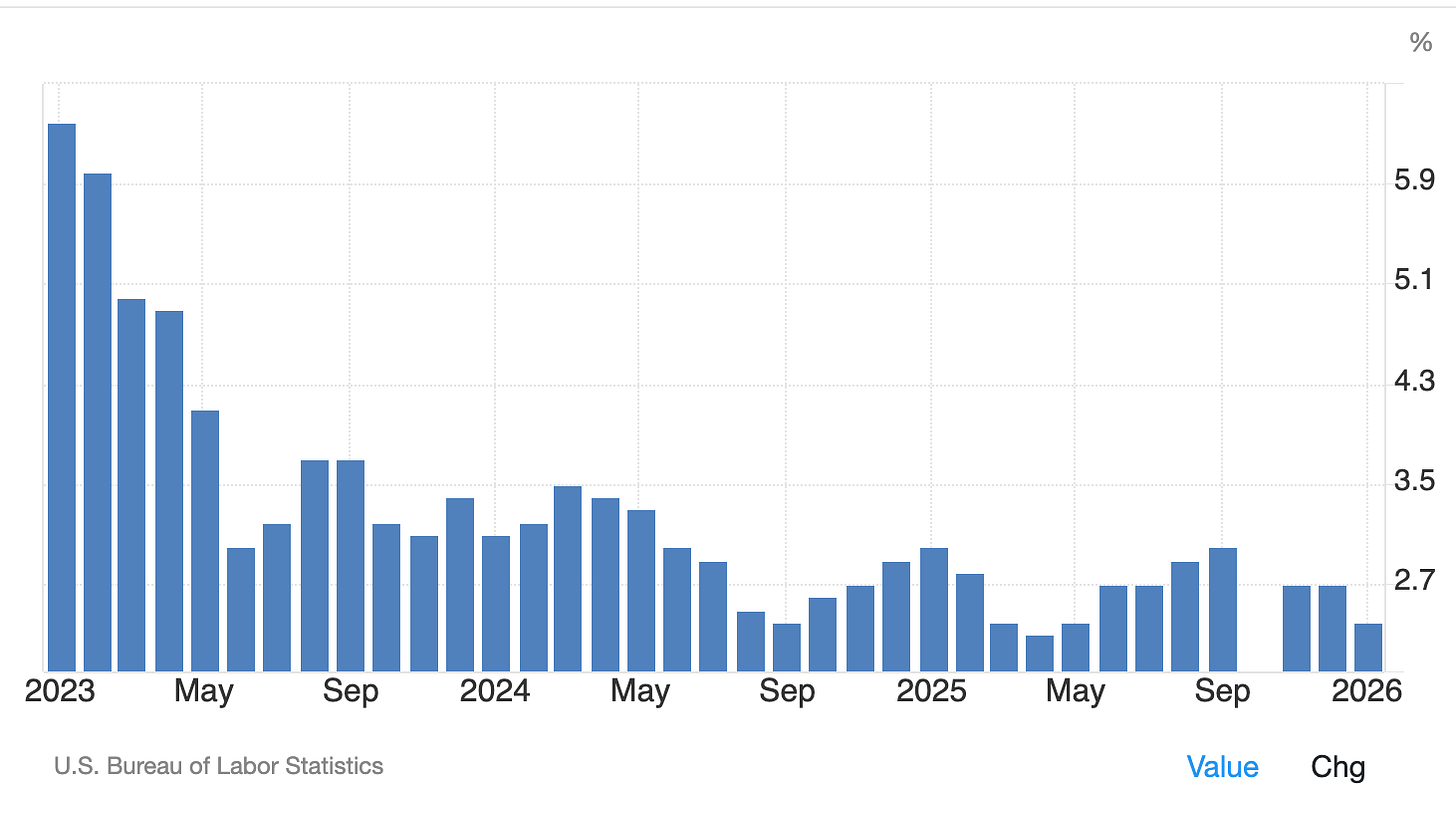

US inflation just came in at 2.4% for January 2026, the lowest since May, and a genuine improvement from where we were two years ago. One paper sounds manageable. In practice, the Fed has been above its 2% target for nearly five years. Five years of your cash losing a race it was never designed to win. At 2.4% annual inflation, a dollar loses about 11% of its purchasing power over five years. Dramatic, but not really, it’s just persistent.

Now, compare that with what’s happening elsewhere. Turkey’s official inflation rate hit 32.87% in late 2025, down from an average of 58.5% the year before, but still the kind of number that rewires a system. Argentina was at 200% inflation when Milei took office and has brought it down to around 30%, which counts as a miracle by Buenos Aires’ standards but is still, objectively, a savings account on fire.

Now you see Saifedean’s point about time preference paying out in real time, and he is right.

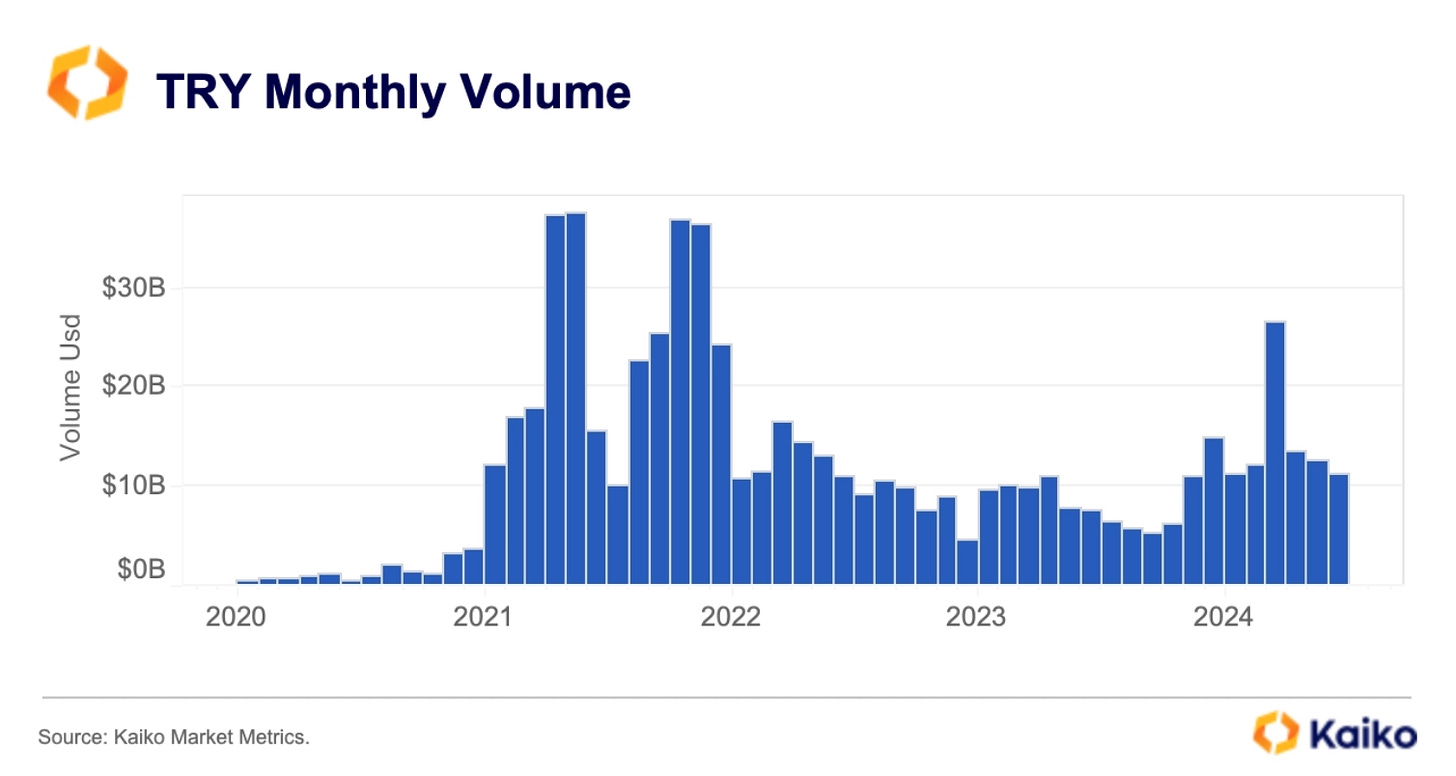

In Turkey, the USDT/TRY trading pair on Binance hit $22 billion in volume in 2024 and now accounts for more than half of all Bitcoin trades on local exchanges. Twenty-five million Turkish citizens are projected to use crypto by 2026. In Nigeria, a sudden naira devaluation in early 2025 sent on-chain crypto volume spiking while it declined in other regions. 46% of Nigerian crypto users now say they’re doing so specifically to hedge against inflation—to keep the things they earned from melting.

This is the “convert fast” twitch Saifedean describes, and once you see it, it’s hard to unsee. Salary hits the account, and the brain goes straight to “How do I get out of this unit into anything else? Dollars, gold, USDT, a plot of land, Bitcoin. It doesn’t matter. The instinct is the same. It’s not greed. It’s not “investment mindset.”

Once you notice that, it’s harder to treat time preference as purely “good habits” or “bad habits”. The unit is nudging you.

From there, the book moves from individual brains to the whole machine.

If people can trust their savings, they’re more willing to actually save. Not just chasing yield, but postponing consumption. That pool of postponed consumption is what we grandly call “capital”. It’s what lets you build things that you don’t pay back for a long time. Like factories, ports, education, R&D—all the unsexy stuff you can’t flip next week.

If saving is punished, you can fake that pool with credit. You don’t need a society that has genuinely put resources aside; you just need a banking system and a central bank willing to blow air into the pipes. You get the same surface-level phenomena (building, investing, hiring), but it’s balanced on a taller, shakier stack of IOUs.

In Saifedean’s telling, honest money gives you patient capital and more grounded growth; easy money gives you bubbles, zombie companies, and constant cycles of “this time is different” right before it isn’t.

I don’t think the line is clean, but the intuition isn’t crazy. If you keep rates unnaturally low and keep pumping liquidity into the system, you can make a lot of projects look viable on a spreadsheet that only works in a permanent zero-rate fantasy. You keep bad companies alive because rolling their debt is cheap. You can make “owning assets” look genius, even if nothing real has improved under the hood.

The book basically treats interest rates as the gossip of the whole economy. In a world where nobody’s fiddling too much, that gossip tells you something true about how patient people are. In a world where central banks are constantly leaning on a scale, the gossip gets distorted. Everyone is still making decisions based on those numbers, but the numbers are half politics, half preference.

You don’t have to hate central banks to admit they can turn that distortion dial a long way before they stop.

And again, if you look at crypto with that lens, it’s not like we’re much better. We love to talk about “free markets” and “sound money,” then spin up protocol-level money printers, yield scams, perpetual leverage. All the same short-term games just with different names and 24/7 trading.

The third stretch in this book is about freedom, but in a very unglamorous sense.

If money design shapes how far into the future you can see, and if distorted interest rates determine how honest your capital formation is, then it’s a small step to ask: How much control do you actually have if the money you save is fully managed by the same entity you are supposed to hold accountable?

Ammous argues that the ability to keep a portion of your wealth in something your government cannot easily dilute is a real, practical kind of freedom.

There’s something to this. Historically, governments have used exactly that lever. Reinhart and Sbrancia’s classic research on financial repression found that real interest rates in the United States and the United Kingdom were negative roughly half the time between 19445 and 1980. This was a policy. The government kept rates below inflation to quietly erode their wartime debt. The financial repression tax amounted to three to four percent of GDP annually. In Mexico, it reached six percent of GDP, equivalent to 40% of total tax revenue.

In other words, the patience tax is not a metaphor. For much of the twentieth century, it was a measurable transfer from savers to the state. You were taxed for your willingness to defer consumption, and the tax had no name voters could point to. A CEPR column from just a month ago calls it “a stealth tax that rewards debtors and punishes savers – especially retirees”.

But here is where the book’s argument starts to thin. Ammous frames “money outside the state” as almost a sufficient condition for freedom.

Where I start to push back is when he makes that the main axis for everything. It is not. States are not just the thing that prints. They also build legal systems, enforce property rights, and coordinate some non-trivial bits of civilisation. You can complain about how they fund themselves (and you should), but opting out of the monetary system is not a magical replacement for politics.

It also matters who actually gets to hold the “good” asset and when. It’s one thing to say anyone can buy Bitcoin. It’s another to look at how access, regulation, education, and simple disposable income actually play out. The ability to step outside a bad currency is not evenly distributed, and the book mostly glides over that.

So, what did this middle stretch of The Bitcoin Standard actually leave me with?

Not “fiat is the root of evil”. But the book definitely leans in that direction more than I’m comfortable with.

What it did do was make it harder to pretend the unit doesn’t matter.

The rupees or dollars or stablecoins you sit in are not just a neutral backdrop to the real action. They’re part of the script. They set how hard it is to be patient, how honest your interest rates are, how real your returns actually are once you measure them in something sturdier, and how exposed you are to other people’s decisions.

You can still decide you prefer the tradeoff. You can still say: I will take soft-ish money paired with social safety nets over hard money and pure markets. That is a valid preference. But at least then you are treating it as a choice and not something that came with the scenery.

Next week, the book finally stops hinting and says the quiet part out loud: all of this is a setup for Bitcoin to walk in as the hard money we forgot we needed. I’m curious to see, reading it now, how the 2018 vision holds up in a world of ETFs, stablecoins, and governments that are very awake to crypto.

See you next week. Until then, keep reading.

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.