Gavin Wood: Building, Breaking, Rebuilding

"The role of CEO has never been one which I have coveted"

There’s a particular type of person who looks at a functioning system and thinks “yes, but what if we rebuilt the entire thing from scratch, properly this time?” Gavin Wood is that person. He’s done it at least three times now, and he’s currently doing it again.

In 2013, Wood met a young programmer named Vitalik Buterin who had an interesting idea about putting a computer on a blockchain. Wood thought this was neat, wrote the first working version of it in a month, invented a programming language for it, and then wrote the first formal specification of any blockchain protocol in history. That computer is now worth about $300 billion and runs most of the decentralised finance industry. Then Wood left, said the architecture was fundamentally limited, and built a different computer-on-blockchain that could run multiple blockchains at once.

That one is worth about $5 billion. Now he’s doing it again, because apparently the second one also has limitations.

This is a profile about that guy. But first, we need to talk about music visualisation.

The Suit-and-Tie Way to Buy Bitcoin.

If you want exposure to crypto but don’t want to touch a wallet, remember 12 words, or worry about rug pulls, Grayscale’s got you.

No private keys to manage

No unregulated exchanges

No steep learning curve

It’s the easiest way for individuals and institutions alike.

The Moodbar Years

Before Gavin Wood was reinventing the internet, he was trying to help people navigate their music collections. His 2005 PhD thesis at the University of York was titled “Content-based visualisation to aid common navigation of musical audio.”

What if you could look at a song and know what it sounded like? What if complex data structures could be transformed into intuitive visual representations?

He built something called Moodbar, which graphically represented audio files. It’s still used in some Linux music applications today. This seems almost embarrassingly quaint now, like mentioning that Steve Jobs once designed a nice font. But the skill was the thing: taking something abstract and computational and making it visible, understandable, usable.

Wood was born in Lancaster, England in April 1980 and was raised by his mother in a single-parent household. He attended Lancaster Royal Grammar School, where he was apparently very good at mathematics and programming. He did a master’s degree, then a PhD, then worked as a researcher at Microsoft Research Cambridge. He consulted for tech companies. He was interested in programming languages and formal verification and game theory.

In 2011, someone told him about Bitcoin. He was unimpressed. The monetary focus didn’t interest him. But the underlying technology did, eventually. What could you do with a blockchain beyond just moving money around?

This is where the story really starts, because in 2013 someone introduced him to Vitalik Buterin.

Ethereum, Or: The First Computer For The Entire Planet

Buterin had been thinking about a blockchain that could run programs, not just track who owned what. Smart contracts, he called them. But thinking about something and actually building it are different problems.

Wood joined what would become the core Ethereum team in early 2014. By January, he had coded the first functional Ethereum client, nicknamed “PoC-1.” Then he wrote the Ethereum Yellow Paper, the first formal specification of any blockchain protocol. Then he invented Solidity, the programming language that people use to write smart contracts. Then he wrote much of Ethereum’s first client implementation.

His guiding vision, which he talked about constantly, was making Ethereum “a computer for the entire planet.” A decentralised platform for applications beyond finance. Games. Voting. Social networks. Whatever people wanted to build.

Wood became Ethereum’s first Chief Technology Officer. Ethereum launched in 2015 and by most measures it worked. It still works. At this point, there are probably several thousand people whose job titles are some variation of “Solidity developer,” and they’re all using a language that Wood invented in 2014.

But by 2016, Wood was restless. He later described Ethereum’s governance as a “technocracy” lacking community-led evolution. There were technical limitations he thought were fundamental. Scalability problems. Interoperability issues. The whole single-chain paradigm seemed wrong to him.

In January 2016, he left the Ethereum Foundation to pursue new ambitions.

Parity And The Wallet Incidents

Right after leaving Ethereum, Wood co-founded Parity Technologies with Jutta Steiner. They built infrastructure: a faster Rust-based Ethereum client called Parity Ethereum, a framework called Substrate for creating custom blockchains.

But 2017 brought two incidents that would become cautionary tales in blockchain security history.

In July 2017, a critical bug in Parity’s multi-signature wallet code allowed a hacker to steal over 150,000 ETH, worth about $30 million at the time. The vulnerability was in a smart contract called wallet.sol. A programmer-introduced flaw allowed the attacker to re-initialise the wallet contract and gain control with a single transaction. This was bad, but at least it was a straightforward hack that could be understood and fixed.

Then in November 2017, an anonymous user accidentally triggered a bug in the Parity wallet smart contract library by calling a self-destruct function. This erased the underlying code that all multi-sig wallets deployed after July 20 relied on. The result: approximately 513,774 ETH (valued around $150-280 million at the time) became permanently frozen in over 500 wallets. The funds weren’t stolen. They were just locked forever, because the code that governed them had been deleted.

The Ethereum community debated solutions, including a controversial hard fork to reverse the effects, but no full remedy was implemented. The frozen funds remained frozen. Parity issued warnings, worked with affected users where possible, and publicly acknowledged both incidents as painful learning experiences.

These events were significant setbacks. They also illustrated a fundamental tension in blockchain development: immutability is a feature until it becomes a problem, and smart contract code that can’t be changed is secure until it has a bug you can’t fix. Wood and Parity Technologies used these incidents to inform better coding practices and security audits going forward, but the November incident in particular remains unresolved to this day.

It’s worth noting that these disasters didn’t derail Parity’s long-term work. The company continued building infrastructure that would eventually underpin Polkadot. But they serve as a reminder that even the people writing the formal specifications of blockchain protocols can ship code with catastrophic vulnerabilities.

Polkadot, Or: The Internet Of Blockchains

Right after leaving Ethereum, Wood co-founded Parity Technologies with Jutta Steiner. They built infrastructure: a faster Rust-based Ethereum client, a framework called Substrate for creating custom blockchains.

But Wood was also working on something bigger. In 2016, he authored what would become the Polkadot White Paper. The idea was a “heterogeneous multi-chain” protocol. Instead of one blockchain doing everything, you could have multiple specialised blockchains that all shared security and could communicate with each other. An “Internet of Blockchains.”

How do you let different blockchains talk to each other securely, when they have different rules and different consensus mechanisms? Wood’s answer involved a relay chain (the backbone) and parachains (specialised chains that connect to it). The relay chain handles security and consensus. The parachains do whatever they need to do.

In 2017, Wood founded the Web3 Foundation to support this vision. Polkadot launched in May 2020. It raised about $144 million in its initial token sale. By late 2021, it had working parachains and a market cap in the tens of billions of dollars.

It is worth noting that Wood also coined the term “Web3” in 2014, back when he was still at Ethereum. He meant it to describe a decentralised internet controlled by users rather than corporations. Now the term means a hundred different things to a hundred different people, many of them involving cartoon apes, but Wood’s original vision was more philosophical: a user-sovereign internet where you control your data and identity.

Kusama, Or: Chaos As A Product

Before launching Polkadot, Wood and the team launched Kusama in 2019. Kusama is described as Polkadot’s “canary network,” which is blockchain-speak for “the place where we try things that might explode before we try them on the expensive network.”

But Kusama has real economic value. Real governance. Real stakes. The tagline is “Expect Chaos” and “No Promises,” which is either radical honesty or excellent marketing, possibly both.

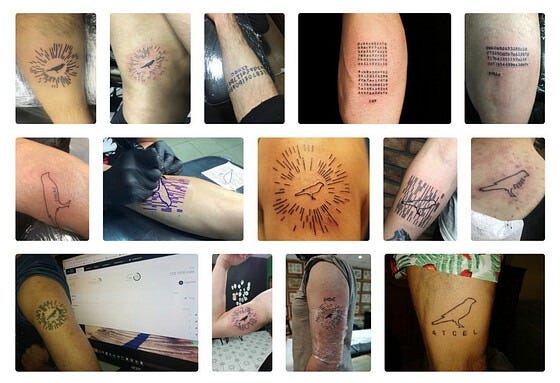

One of the more interesting experiments was the Kusama Society, where people could get KSM tokens for getting Kusama-themed tattoos. This was partly a social experiment and partly an early version of proof-of-personhood. A lot of people got the tattoos. One person who joined early made about $100,000 from his tattoo when KSM prices peaked.

The Problems With Success

By 2021-2022, Polkadot was live and working. Parachains were running. The first parachain auctions happened in December 2021, with enormous amounts of capital locked up in crowdloans. Everything was, by the standards of blockchain projects, going well.

And then Wood started saying the whole thing needed to change.

In late 2024, he announced what the community called an “ideological bombshell”. He nominated Proof-of-Stake, the consensus mechanism he had designed for Polkadot, was “dragging down” the network’s security model. He proposed eliminating traditional staking rewards and moving toward a proof-of-personhood system instead.

This was not a small pivot. The entire economic model of Polkadot was built around staking DOT tokens and earning rewards. Now Wood was saying maybe that was wrong? Maybe instead of economic-based consensus, we need identity-based consensus?

He also proposed radical changes to Polkadot’s issuance curve, essentially cutting inflation dramatically. The treasury, which had been spending about $37 million on marketing, suddenly had to become much more conservative. There were debates about governance effectiveness. About whether power was too concentrated among large token holders.

JAM, Or: The Third Computer For The Planet

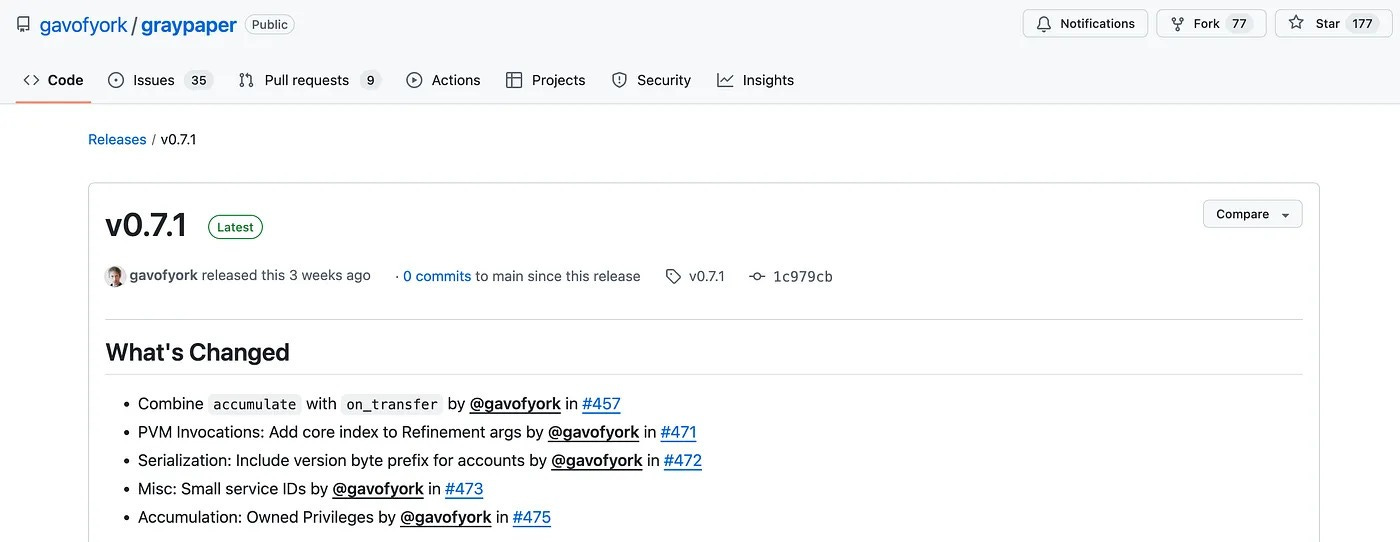

In 2024, Wood unveiled JAM (Join-Accumulate Machine), detailed in what he called the “Gray Paper.” JAM is meant to transform Polkadot from a platform for blockchain interoperability into a more general-purpose computing platform.

The technical details involve things like “core time” and “accumulation” mechanisms. The philosophical point is that Wood thinks blockchain architecture still has fundamental limitations that need solving.

JAM is an evolution of Polkadot. Wood has always preferred systematic improvement over revolutionary replacement. But it’s still the third time he’s said “the computer we built is good but we can build a better computer.”

To incentivise development, Wood and the Web3 Foundation announced a prize of 10 million DOT for additional JAM implementations. At current prices that’s about $32 million.

The CEO Who Didn’t Want To Be CEO

In October 2022, Wood stepped down as CEO of Parity Technologies. His blog post explaining the decision was remarkably candid: “The role of CEO has never been one which I have coveted. I can act at being a CEO well enough for a short while, but it’s not where I’m going to find eternal happiness. Anyone who has worked with me knows where my heart lies. I’m a thinker, coder, designer and architect.”

He said he worked best asynchronously, that a great day for him was “taking 10 hours straight to think out some problem, prototype something or collapse some disparate thoughts into an article.”

He became Parity’s Chief Architect instead, then later Chief White Space Officer, a title that perfectly captures his preference for working on things that don’t exist yet.

But then in August 2025, he came back as CEO. The announcement said “the foundations are now in place” and the market was ready for the next phase.

Wood’s blockchain projects keep trying to escape this uniformity trap. Ethereum was one computer for everyone. Polkadot was many specialised computers that could talk to each other. JAM is attempting something even more flexible. Each iteration is trying to build systems that allow for difference, for specialisation, for context.

The answer to power is transparency and verification, not trust. Build systems where trust isn’t necessary. Build tools that work regardless of the motives of the builders.

For years, Parity’s strategy was staying in the background as a tech provider. Build the platform, let others build the products. Wood concluded this wasn’t enough. If he wanted to see better products on Polkadot, Parity would have to build them. The list includes: a proper Polkadot app, a desktop application, a website that actually works, better governance tools. Also a DOT-collateralised stablecoin, though the community is currently voting that down (they like the idea, just not the specific implementation).

Looking at Wood’s career, there’s a clear pattern: Build something. Realise it has fundamental limitations. Build something better. Realise that has limitations too. Build something even better. You can view this as either admirable iterative improvement or slightly exhausting perfectionism.

But there’s a third interpretation that’s less flattering: Maybe this is just abandoning things when they get hard? Ethereum needed years of grinding work to scale and achieve product-market fit. Wood left in 2016. Polkadot needed similar grinding work to build adoption and compete with newer, faster chains. Wood stepped back in 2022, then returned in 2025 with plans to fundamentally restructure it. At what point does “iterative improvement” become “chasing the next shiny thing because making the current thing succeed at scale is boring and difficult”?

The charitable interpretation is that Wood correctly identifies architectural limitations early, before they become insurmountable, and has the courage to start over rather than optimise a fundamentally limited design. The less charitable interpretation is that he’s better at inventing new systems than at the unglamorous work of making existing systems win in the market. Probably it’s both.

His estimated net worth is around $450 million. Outside blockchain, he pursues photography, music, philosophy. He holds a black belt in Taekwondo. In 2022, he donated $5.8 million to Ukraine.

Gavin Wood keeps building computers for planets, and each time he builds one, he immediately starts thinking about how the next one should work better. At this point, it’s probably just what he does.

That’s Gavin Wood. More profiles coming.

Until then … stay curious,

Thejaswini

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.