In 1993, a 22-year-old working a $6.85-an-hour job in the basement of a university supercomputing center wrote some code that made the internet clickable. Before that, accessing the web required memorising Unix commands.

After that, anyone could do it.

Thirty-two years later, that same person is advising the U.S. government on which regulatory agencies to dismantle. The agencies in question happen to oversee some of the companies he’s invested $7.6 billion in.

This is not a coincidence.

Marc Andreessen’s career reads like a case study of what happens when someone figures out the future early and then spends decades making sure nothing stands in their way. He’s created the first mainstream web browser, taken a company public at 24, survived a startup that nearly bankrupted him, reinvented how venture capital works, and bet bigger on crypto than almost any institutional investor on Earth.

He’s also blocked critics on Twitter, fought against affordable housing near his mansion, compared India’s rejection of Facebook to economic catastrophe, and positioned himself as the intellectual architect of a movement to gut the regulatory state.

Understanding Andreessen means sitting with contradictions that don’t resolve cleanly. The same brain that made the internet accessible to non-technical users now publishes 5,000-word manifestos about why technology should be accelerated beyond all limits. The man who got crushed by Microsoft’s monopoly tactics is now helping design policies that could make it easier for new monopolies to form.

This is a story about leverage. How you get it, how you use it, and what happens when someone who’s already reshaped how we use computers decides the next thing to reshape is how we govern them.

Let me start with a letter.

GigaStar: Creator Economy Meets Investment

Creators now can offer a share of their future revenue to their fans and investors. GigaStar makes it possible!

Build your creator brand, raise funds, retain your IP

Investors gain access to “Channel Revenue Tokens (CRTs)” that represent revenue share rights

Record-breaking results: multi-million dollar channels raised, thousands of investors joined

Whether you’re a creator or an investor looking to get ahead of the creator economy boom, GigaStar is the bridge.

Discover GigaStar!

In August 2022, someone leaked a piece of correspondence that Marc Andreessen and his wife had sent to the mayor of Atherton, California. Atherton is the wealthiest zip code in America, with the median home selling for over $7 million. Marc Andreessen lives there.

The letter concerned a proposal to rezone a single property for multifamily housing. Andreessen wanted the proposal “IMMEDIATELY REMOVED.” The development would “MASSIVELY decrease the values of our homes,” create “IMMENSE” noise pollution, and dramatically increase traffic.

The capitalisation was his, not mine.

Two years earlier, Andreessen had published an essay called “It’s Time to Build,” that went viral during the COVID lockdowns. In it, he argued that America had lost its will to construct housing, infrastructure, and factories. Regulatory paralysis and cultural complacency were killing us and we needed to build our way out.

The Atherton letter became exhibit A in the case that Silicon Valley’s “build” rhetoric has limits. Specifically, the limits of their own property lines.

But dismissing Andreessen as just another hypocritical billionaire misses something important. Because whatever his personal contradictions, he’s been right about technology’s trajectory more consistently than almost anyone else over the past three decades. And right now, he’s betting that the next phase requires removing the referees entirely.

Whether that’s visionary or reckless is the question. Let’s start at the beginning.

Andreessen’s origin story is genuinely impressive. A small-town Wisconsin kid, teaching himself BASIC on a TRS-80 from the library, ends up at the University of Illinois working at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications. In 1993, at 22, he created Mosaic, the first web browser that didn’t require a PhD to operate. Sometimes simplifying solves a lot of problems. The innovation was simpleimages displayed inline with text. It changed everything. Suddenly, the web looked like a magazine instead of a Unix terminal.

Within a year, 2 million people had downloaded it. The internet went from a niche, exclusive club for computer nerds to cultural phenomenon overnight. Jim Clark, the founder of Silicon Graphics, saw what was happening and recruited Andreessen to California. They founded Netscape in 1994. By August 1995, Netscape’s IPO made Andreessen worth $58 million at age 24. The stock opened at $71, more than double its offering price, despite the company having exactly zero profits.

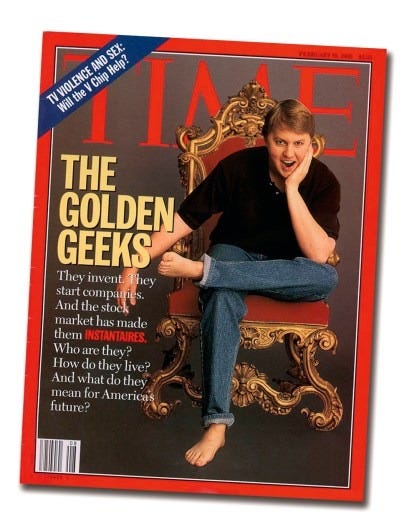

A successful IPO was also the starting gun for the dot-com bubble. Every founder with a pitch deck and a dream suddenly had a blueprint, which is to get big fast, go public, and worry about profits later. Andreessen became the face of this new economy. Time magazine put him on the cover, barefoot and sitting on a throne like a digital emperor. He famously predicted that Netscape would reduce Windows to a “poorly debugged set of device drivers,” which was less a technical forecast and more a declaration of war.

The lesson was about power. Microsoft crushed Netscape by controlling the platform. If you don’t control the platform, someone else controls your oxygen supply.

What happened next is important because it doesn’t fit the typical Silicon Valley narrative. In 1999, Andreessen and Ben Horowitz founded Loudcloud, essentially building Amazon Web Services before AWS even existed. Brilliant idea. Catastrophic timing. They launched just as the dot-com bubble was imploding. Their customers, mostly startups burning venture capital, went bankrupt en masse. Loudcloud’s stock crashed from $6 to $0.35.

This is where Andreessen’s narrative gets interesting.

Most Silicon Valley origin stories are smooth arcs from garage to IPO to billions. Andreessen’s includes a near-death experience, when Loudcloud burned through its cash in the dot‑com crash, laid off hundreds of employees, and came within inches of bankruptcy before pivoting into Opsware.

They renamed it Opsware. It was brutal. It took years. But in 2007, HP bought Opsware for $1.6 billion.

That crucible matters because it distinguishes Andreessen from the “fair-weather” founders who only know what it’s like when everything is on an upward trajectory. He knows what it’s like when the money runs out and the phone stops ringing. He’s operated a sinking ship in a hurricane. That experience hardened him, and gave him credibility as an operator, not just a visionary.

The Venture Capital Machine

In 2009, amidst the wreckage of the financial crisis, Andreessen and Horowitz launched their venture capital firm with $300 million. The timing was perfect. Valuations were depressed. Competitors were pulling back, and Andreessen had a thesis about how venture capital was broken.

Traditional VC firms were small partnerships. A few general partners, maybe some associates, portfolio companies got capital and a board seat, but not much else. Andreessen Horowitz built something different: the “Agency Model,” inspired by Hollywood talent agencies. They hired hundreds of people across various functions like recruiting, PR, business development, legal, and regulatory affairs. Portfolio companies didn’t just get money; they got a full-service support apparatus.

This model forced the entire industry to professionalise. Suddenly, every VC firm had to offer operational support or risk losing deals. Andreessen also understood media in a way most VCs didn’t. He and Horowitz blogged, tweeted, appeared on podcasts,and controlled their own narrative instead of relying on tech journalists. They positioned themselves as “founder-friendly,” promising they’d never replace a founder-CEO (a common fear after Steve Jobs was ousted from Apple).

The results were spectacular. They invested in Facebook, Twitter, Airbnb, GitHub, Pinterest, Slack, and Lyft. Their funds generated returns that made them legends. By some estimates, their internal rate of return hit 50%, making them one of the most successful VC firms in history. Andreessen published “Why Software Is Eating the World” in 2011, a manifesto arguing that software companies would devour every industry, from retail to defense to agriculture. That thesis justified the massive valuations of the 2010s Unicorn boom. It became accepted wisdom.

The Crypto Godfather

In 2013, Andreessen began investing in Bitcoin and the broader crypto ecosystem. At the time, this was genuinely contrarian. Most serious institutional investors viewed crypto as a scam, a Ponzi scheme, or digital tulips. Andreessen compared the skepticism to what he’d faced with the internet in 1993. He saw a pattern: new technology, dismissed by incumbents, poised to disrupt everything.

Andreessen Horowitz became the first blue-chip VC firm to launch dedicated crypto funds, eventually raising over $7.6 billion across multiple vehicles. They invested in Coinbase, Solana, Uniswap, OpenSea, basically the entire infrastructure layer of crypto. Andreessen’s involvement lent crucial legitimacy to the sector. When banks were debanking crypto startups and regulators threatened bans, his presence signaled to other institutions that this was real, not criminal.

The firm developed the “progressive decentralisation” playbook: start centralised to iterate quickly, then gradually hand control to token holders. This was designed to navigate SEC regulations, trying to prove tokens weren’t securities because the networks were “sufficiently decentralised.” It was regulatory arbitrage wrapped in revolutionary rhetoric.

In late 2021, Twitter founder and Bitcoin maximalist Jack Dorsey launched a public attack on the Web3 narrative. His tweet became infamous: “You don’t own ‘web3.’ The VCs and their LPs do. It will never escape their incentives. It’s ultimately a centralised entity with a different label.”

Dorsey’s argument was that Andreessen Horowitz was engaging in the very kind of centralisation they claimed to oppose. By owning massive stakes in “decentralised” protocols and using those tokens to vote in governance, they were effectively the central bank of the new internet. They were extracting rents from users, just like Web2 platforms, but masking it with liberation rhetoric.

Andreessen blocked Dorsey on Twitter. Dorsey responded with a screenshot, mocking the VC’s inability to handle dissent. The “block” became a meme, a symbol of the rift between Bitcoiners (who value immutability and zero VC influence) and Web3 VCs (who value experimentation and token-based business models).

Critics started digging into the mechanics. The allegation was that Andreessen Horowitz would invest in a protocol at the seed stage for pennies per token, hype it through their massive media machine, watch it list on Coinbase (also an a16z portfolio company) at inflated prices, and then sell to retail investors as vesting schedules unlocked. The VCs would realize 1000x returns while retail held the bag when prices crashed. Legal? Yes. But fundamentally contradicting the egalitarian ethos of crypto.

The Political Radicalisation

In October 2023, Andreesen published “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto,” a 5,000-word document that felt less like a business thesis and more like a political declaration.

The manifesto identified a “coalition of the demoralised” including tech ethicists, trust and safety teams, ESG investors, and regulators, as enemies of civilisation. He argued that technology was the only source of growth and abundance, and that any restriction on it was a restriction on human life itself. He embraced “Effective Accelerationism” (e/acc), advocating for accelerating AI and capitalism to their absolute limits to overcome scarcity.

Critics noted disturbing parallels to early 20th-century Italian Futurism, which celebrated speed, violence, and war as societal hygiene. The manifesto felt less like optimism and more like techno-feudalism. A world run by engineer-kings, unaccountable to democratic oversight, with the rest of humanity as passive consumers of their abundance.

By 2024, Andreessen’s alienation from the Democratic Party was complete. He felt the Biden administration, particularly SEC Chair Gary Gensler and FTC Chair Lina Khan, was waging war on tech through aggressive regulation and “Operation Choke Point 2.0” (debanking crypto companies). He formally endorsed Donald Trump, articulating the “Little Tech Agenda.”the thesis that Big Tech loves regulation because they can afford compliance costs, which act as moats against startups. Little Tech (crypto, AI startups) dies under regulation.

Following Trump’s victory, Andreessen became deeply involved with the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), an advisory commission led by Elon Musk. Although he called himself an “unpaid intern,” reports indicated he was a key architect of its strategy. The commission’s goal was to slash federal spending and dismantle the “administrative state.” Andreessen specifically targeted agencies that had investigated his portfolio companies- the CFPB (which had probed fintechs like Greenlight) and the SEC (which had sued Coinbase).

This is regulatory capture at its most naked: a billionaire VC advising the government to destroy the regulators overseeing his investments. The DOGE initiative aimed to cut agency workforces, ostensibly for efficiency, but functionally removing oversight of the industries Andreessen profits from. But despite the hype and brutal cuts, DOGE has fallen far short of its own promises: court rulings and political backlash stalled many of its biggest layoffs, Musk quietly exited, and the White House has now confirmed the department has been disbanded with most of its projected ‘trillions in savings’ unrealised.

The Contradictions

Here’s what I keep coming back to: Marc Andreessen is extraordinarily good at identifying where the world is going and positioning himself to profit from it. He visualised the web with Mosaic. He commercialised it with Netscape. He industrialised venture capital with a16z. He legitimised crypto for institutions. He’s now trying to deregulate everything so his portfolio companies can operate without friction.

But his blind spots are massive. His “techno-optimism” often resembles “techno-solipsism,” a belief that technology solves all problems while ignoring displacement, inequality, and community rights. He champions decentralisation while consolidating power in mega-firms. He preaches building but obstructs it when it inconveniences him personally.

For example, Andreessen’s firm a16z voted ‘no’ on the Uniswap fee switch, a proposal that would have given more control and revenue to token holders, illustrating how his ‘techno-optimism’ aligns with consolidating power in mega-firms rather than empowering decentralisation.

The Free Basics controversy in India in 2016 is revealing. Facebook tried to launch a service providing free access to a limited “walled garden” of the internet for India’s rural poor. India’s telecom regulator banned it, citing net neutrality violations. Andreessen exploded on Twitter: “Anti-colonialism has been economically catastrophic for the Indian people for decades. Why stop now?”

The implication was that India’s sovereign decision to reject a Western corporation was backward, rooted in irrational resentment. Silicon Valley knew what was best for the developing world better than the people themselves. Mark Zuckerberg publicly rebuked him. Andreessen apologised and deleted the tweet. But the mask had slipped.

Marc Andreessen is the avatar of a specific worldview that the world would be better if it were run like a software company, with engineers making decisions based on efficiency rather than messy democratic processes. He’s convinced that technology is the solution to every problem, that regulation is always captured, and that the best thing the government can do is get out of the way.

And maybe he’s right about some of it. Regulation can be captured. Government can be sclerotic. Technology has solved genuine problems and created real abundance. But the flip side is also true. Unregulated markets create monopolies. Technology displaces workers. Abundance for some often means precarity for others.

Andreessen’s current project, essentially trying to dismantle the administrative state so his crypto and AI investments can flourish without oversight, is the logical endpoint of his philosophy. Now he’s trying to rebuild the regulatory architecture of the United States to favor his portfolio.

Whether you think that’s visionary or terrifying probably depends on whether you believe the people building the future should also be the ones deciding the rules. Andreessen clearly believes they should. He’s betting billions on it. And right now, with his guys in power and the regulators on the defensive, that bet is paying off.

What happens when the thing he’s building breaks? Because things always break. The dot-com bubble burst. Netscape got crushed. Loudcloud nearly died. The crypto markets crashed. And when the next crash comes, when the thing that looked like inevitable progress turns out to be another cycle, will the people who got hurt by the lack of guardrails remember that Marc Andreessen spent years trying to remove them?

I don’t know. But I do know this. The man who got famous for making the internet easy to use has spent the last decade pushing the boundaries of innovation and regulation. His approach to complexity reflects a deep understanding of the evolving digital landscape, crafting systems that challenge traditional frameworks and encourage new forms of accountability and transparency. What some see as obfuscation, others might view as pioneering strategies to navigate and shape the future of technology and governance.

He’s envisioning a future where builders have the freedom to innovate without unnecessary barriers. For those in the building seat, this means unprecedented opportunity to create and shape the world. And while experiments inevitably face challenges, such trials drive progress and learning. Marc Andreessen’s strength is in weathering those storms and coming out stronger, continuing to lead innovation no matter what happens.

That’s Marc. See you again next week with another profile.

Until then, stay curious?

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.