Ownership Coins 🪙

Corporate law took decades to protect shareholders. DeFi is trying to compress that timeline.

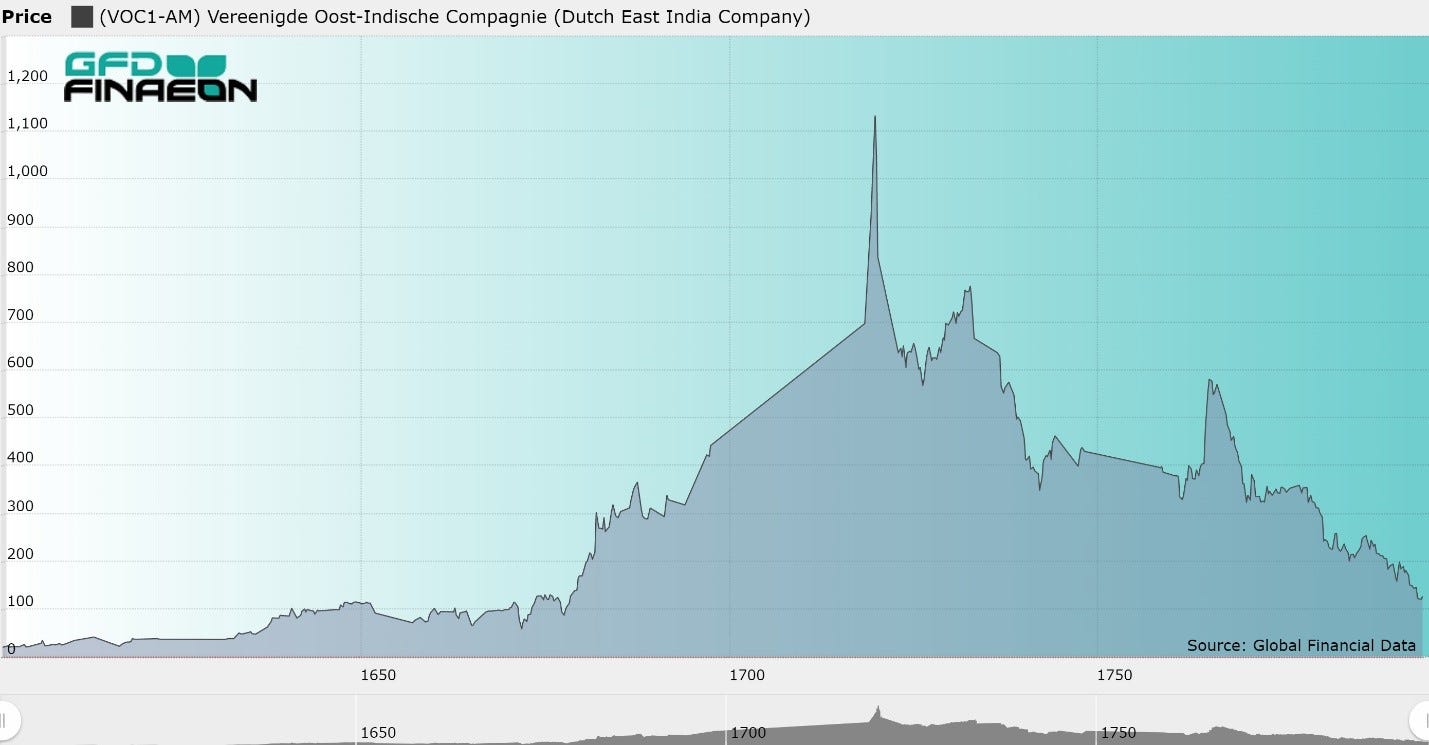

The Dutch East India Company changed everything in 1602 after it introduced limited liability companies. It invented a way to finance companies and earn from their profits by just holding its shares. This enabled a division between company ownership and execution.

Today, we can clearly see the division of power in big public corporations like Microsoft or Apple. The shareholders are entitled to a share of the company’s properties and its profits; the board members pass budget approvals on behalf of the shareholders, while the CEO runs the company.

However, this structure took decades to form. Before corporations, if you wanted to trade spices in India, you had to fund the entire ship yourself. If the ship sank, you were personally bankrupt. Creditors could even take your house or throw you in prison.

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company changed the dynamics. Instead of funding one voyage, investors bought “shares” in the company itself. This created Limited Liability: if the company went bust, you only lost the money you put in. Your house and bed were safe.

There was no written law to ensure the interests of the investors. So naturally, as railroads spanned the globe and companies became massive, “Corporate Raiders” and “Robber Barons” were born. They would often lie to investors, print fake shares, or use company money as their personal piggy bank. Shareholders were left holding the bag while the owners lived in gold-plated mansions.

This led to distrust among shareholders, and stock markets tanked. The 1929 Stock Market Crash was the turning point. Governments realised that if people do not trust the “game,” the economy dies. This led to the creation of the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) and modern Fiduciary Duty.

Today, rules protect you.

Transparency: public companies must release audited financial statements (10-Ks) every year.

Anti-Fraud: It is a federal crime to lie to shareholders to pump a stock.

Appraisal Right: If a company is sold for a suspiciously low price, shareholders can sue to get the “fair value” of their shares.

Did Aave Just Hide $10 Million?

Onchain governance currently sits somewhere between the 1800s corporate frauds and the events that led to shareholder protection by law.

At Aave DAO, in particular, participants are in the process of continuous discussions and making proposals to arrive at the answers that on-chain DAOs have never been able to answer: who owns the protocol, and who controls it?

A simple question in theory, but coordinating people with different interests tends to complicate simple things.

The spark that led to the Aave governance debates was worth $10 million. For years, the Aave DAO and Aave Labs coexisted in a state of mutual understanding. The DAO funded the protocol, and Labs built the interface.

However, that peace was shattered in December when members of the DAO realised that, suddenly, $10 million in annual swap fees that should be flowing to the DAO treasury were now being redirected to a private Aave Labs wallet.

This happened after Labs swapped ParaSwap for CoW Swap on the official Aave frontend, which changed the value accrual mechanism from ParaSwap referral fees to CoW Swap frontend fees.

At its core, interface fees have been the most obvious monetisation choice for teams leveraging the underlying protocol - we can see it with Uniswap Labs and now Aave labs.

If team is perceived to be profiting off a public commodity (user liquidity) without passing rewards, it could hurt how token holders perceive the firm. The token’s price could collapse overnight, as users will have no reason to keep holding onto them.

Conversely, a team that continuously sells its governance token to incentivise developers and manage its operational expenses is signalling that it is willing to give up protocol control in exchange for an extended runway.

This disconnect between governance rights and incentives is why interface fees has been trendy among protocols that have scaled meaningfully.

The technical justification from Labs was that since they built the frontend, they should keep the frontend revenue. But nobody had formally established that boundary. Tokenholders had assumed the whole Aave IP and brand value, and by extension, the interface revenue, belonged to the DAO. Labs had assumed interface operations were their domain. Both assumptions had surprisingly coexisted for years.

By the end of December, two proposals emerged from DAO members. One of them from Ernesto Boado, former Aave Labs CTO. He proposed the transfer of IP and brand ownership to the DAO, along with the full pass-through of the revenue it earns, while Stani responded with an Aave vision roadmap that implicitly required maintaining the current power structure.

Five days after Boado’s proposal, Aave Labs escalated it to Snapshot without his knowledge or consent, with voting scheduled December 22-25, ending Christmas Day. Boado publicly condemned the move, urging supporters to abstain. The vote failed with 55% opposed and 41% abstaining in protest - just 4% voted in favour, but by then, AAVE had dropped 25% and roughly $500 million in market cap had evaporated.

The price action was a result of the uncertainty in the value of the underlying token. If Stani and team can exert influence on the DAO, then what value does the token really hold?

Aave had grown into a $2 billion protocol without answering basic questions. Does the DAO own the Aave brand? Does Labs work for tokenholders or alongside them?

Both sides made reasonable arguments. Labs built the interface, defended it against an SEC investigation for four years, and bears ongoing operational costs. Tokenholders funded development, paid for the rebrand, and provided the liquidity that makes the brand valuable. The protocol is open-source; anyone can build competing interfaces. But users choose aave.com because of the brand recognition the DAO helped create.

The problem is that both positions are internally consistent. Traditional corporate law spent decades developing frameworks to resolve ownership and control dilemmas. DeFi skipped that process, and the governance breakdowns we see happening are a price we are paying to get there.

Different protocols are attempting different solutions to the same underlying problem.

The DeFi Governance Question

Hyperliquid eliminated the governance question. Ninety-seven per cent of trading fees flow directly into HYPE buybacks through the Assistance Fund. In over a year, the protocol has done over $700 millions+ in buybacks. Meanwhile, the team maintains complete operational authority. The codebase is closed-source. There’s no DAO oversight of the buyback mechanism.

But tokenholders do not need to trust management’s intentions because value sharing is encoded in the protocol itself. While tokenholders do not govern strategy or own the underlying protocol as such, they profit automatically from platform growth, and that arrangement seems to be working so far.

Uniswap went through its share of struggles, too. The team spent five years avoiding the question of tokenholder alignment. While the fee switch existed in the codebase since 2020, it was never activated.

The December 2025 “UNIfication” proposal resolved the ambiguity: 100% of protocol fees now flow to UNI burns, Labs eliminated its interface fees, and 100 million UNI were retroactively burned to compensate for years of missed value accrual.

Uniswap Labs owns the brand and IP and handles product development; meanwhile, DAO owns the smart contract and has control over the revenue and the underlying treasury.

Jupiter tried community governance from 2024 to mid 2025, until the team decided to pause it. Months of debates over airdrop allocations and team allocations led the team to pause DAO voting in mid-2025, citing “breakdown in trust” and “perpetual FUD cycles,” which were hindering product development.

Their 2026 “Going Green” framework reduced community decision-making scope while implementing tokenholder-friendly economics through zero net emissions and reduced dilution. This is similar to Hyperliquid’s direction, where tokenholders benefit from the protocol’s revenue, but the protocol’s brand ownership and control remain with the team.

Most of the teams mentioned are chasing economic alignment with the tokenholders, while the ownership of the interface and its control remains with the protocol team.

Will Aave (Labs) Win?

Aave’s February 2026 “Aave Will Win“ framework attempts a more forward path - providing economic alignment along with the brand IP. The protocol promises all revenue - product revenue, swap fees, interface income, and institutional services to flow to the DAO treasury.

In exchange, Labs receives $42.5 million in stablecoins ($25 million primary + $17.5 million in milestone grants), 75,000 AAVE tokens, and a mandate to build V4. Meanwhile, an Aave Foundation would hold brand IP with DAO oversight.

DAO members see it as an expensive pursuit, and rightly so, the stablecoin ask alone is 42% of the DAO’s non-AAVE reserves. The total ask of roughly $50.7M is 31.5% of the entire treasury. Additionally, the 75K AAVE token would increase Labs’ voting power, while the overall share remains unknown.

Other than funding, the proposal is also a bit vague on the ownership structure of the Aave Foundation and whether it will have independent decision-making from Labs. Even the 100% revenue distribution remains vague and assumes trust in Labs for an honest and full revenue picture.

All in all, the proposal places a lot of trust in Aave Labs. With the various events that led to this proposal, trust is a commodity that is running short in the DAO - Labs relationship.

Whether the proposal is reasonable depends on what governance tokens were supposed to provide. If the value proposition was ‘equity with trust-based alignment,’ Aave’s framework delivers that.

If the value proposition was ‘equity with law-enforced community control over protocol IP,’ the framework falls short.

Looking Ahead

The pattern emerging across DeFi protocols is towards economic alignment rather than governance rights as the primary tokenholder benefit.

Hyperliquid’s buybacks, Uniswap’s fee-to-burn mechanism, Jupiter’s pause on governance while maintaining economic alignment, and Aave’s proposed revenue redirect, with trust-based brand ownership - each represents movement away from active governance toward passive value accrual.

This resembles traditional corporate governance. Shareholders do not run companies but elect boards to vote on major transactions. Meanwhile, they receive dividends and sell their shares if they disagree with management. The operational authority always rests with executives.

Corporate law evolved toward that separation because the alternative of shareholders making operational decisions doesn’t scale beyond small partnerships.

DeFi is compressing the traditional timeline.

The question is whether the DAO model can survive the moment when it has to answer the ownership questions it has been avoiding since its inception. Aave is writing the first draft of that answer.

(Re)thinking about governance tokens,

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.