Hello,

Over the past year, a subtle change has started to emerge across the internet. More and more systems are beginning to focus less on how users interact with them and more on what users are trying to achieve. Instead of emphasising clicks, steps, or instructions, these systems are now starting with intent.

This shows up in different places. In finance, users specify outcomes and let software handle execution. In commerce, agents negotiate prices and timing on behalf of users. In search and productivity tools, people are increasingly describing goals instead of navigating menus or workflows.

This shift is often described as the Intent Economy. It refers to systems where intent becomes the primary input, and execution is delegated to software that competes to fulfil it under certain constraints. Until now, most of the internet has been built around interfaces. Users were expected to translate what they wanted into actions that the system could understand. That meant learning tools, making choices, and managing trade-offs manually.

What is changing now is that intent itself is starting to be captured and acted upon directly. Today, we’ll take a closer look at how intent-based systems are emerging across the internet.

What the Internet is Optimised For

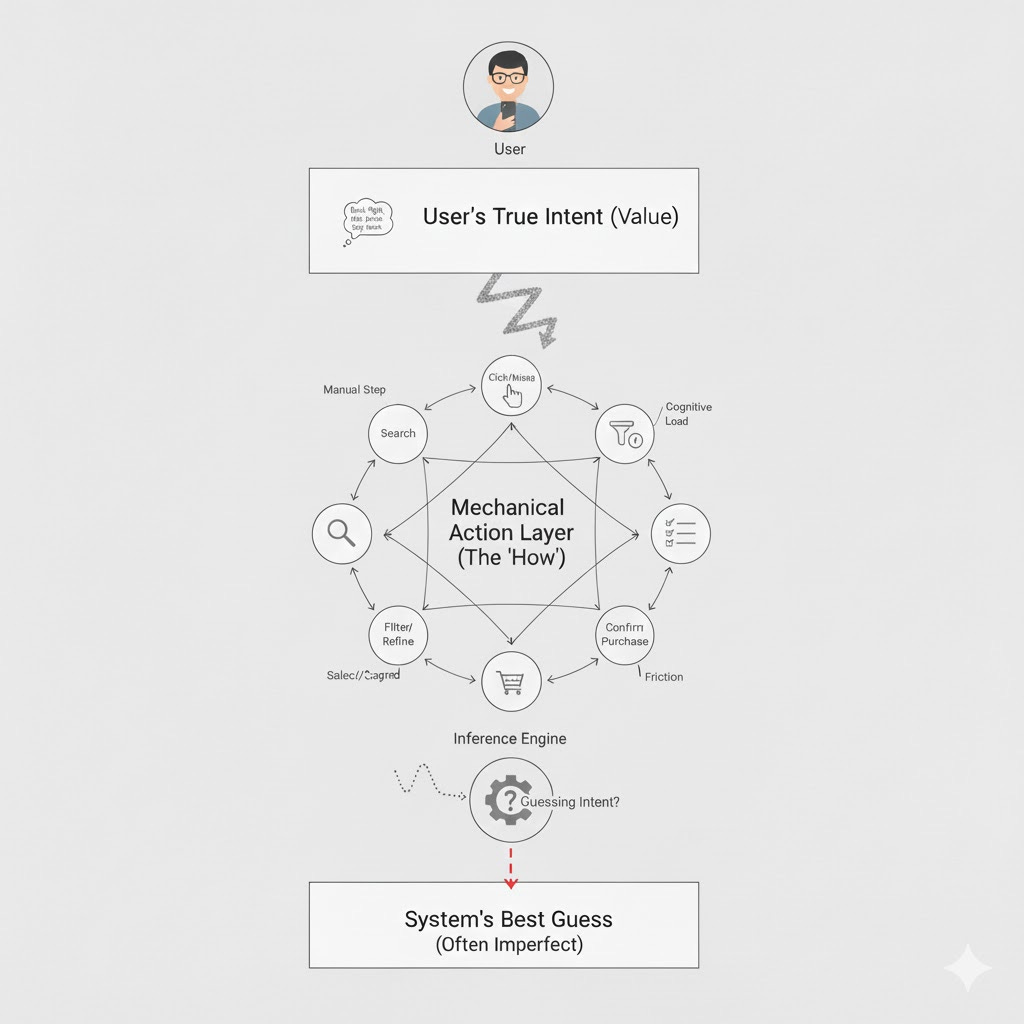

Most internet systems do not work directly with intent. They work with actions. When users want something done, they are expected to express that through a sequence of steps: searching, clicking, filtering, selecting, comparing, and confirming. The system does not receive a clear statement of what the user wants. It receives signals about what the user is doing and tries to infer intent from those signals. This approach made sense when systems were simpler. The number of options was limited, execution paths were more understandable, and users could reasonably translate what they wanted into actions with minimal effort or risk.

As the internet grew, this assumption quietly stopped holding. Markets became larger and more fragmented. A single outcome often involved multiple venues, prices, and intermediaries. Yet, the interaction model remained unchanged. Users were still required to decide how something should be done, even when they lacked the information or context to make informed decisions. Booking travel, moving money, purchasing goods, or coordinating work increasingly meant managing complexity. The control stayed with the user, but the understanding did not.

At the same time, platforms started optimising around what they could easily monetise. User actions were visible, and so clicks, engagement, time spent, funnels, and conversions became the dominant signals systems responded to, not because they reflected user success, but because they were measurable and monetizable. Over time, these proxies began to replace intent as the primary optimisation target. Systems became better at guiding users through flows, not at minimising the effort required to reach an outcome. The longer and more involved the process, the more opportunities there were to extract value along the way.

The result is an internet where users usually arrive with clear objectives, but platforms respond by pulling them into flows and processes designed to keep them engaged for longer. Instead of reducing the work needed to reach an outcome, users are asked to compare options, manage trade-offs, and move through extended paths, even though software has access to far more data and computational capacity than the user does.

Intent has always been present, but it was never treated as a direct input. Systems relied on user actions instead, leaving users to handle coordination and decision-making themselves. The friction that exists today is not accidental. It results from systems reacting to behaviour instead of acting on stated goals.

Making Intents Explicit

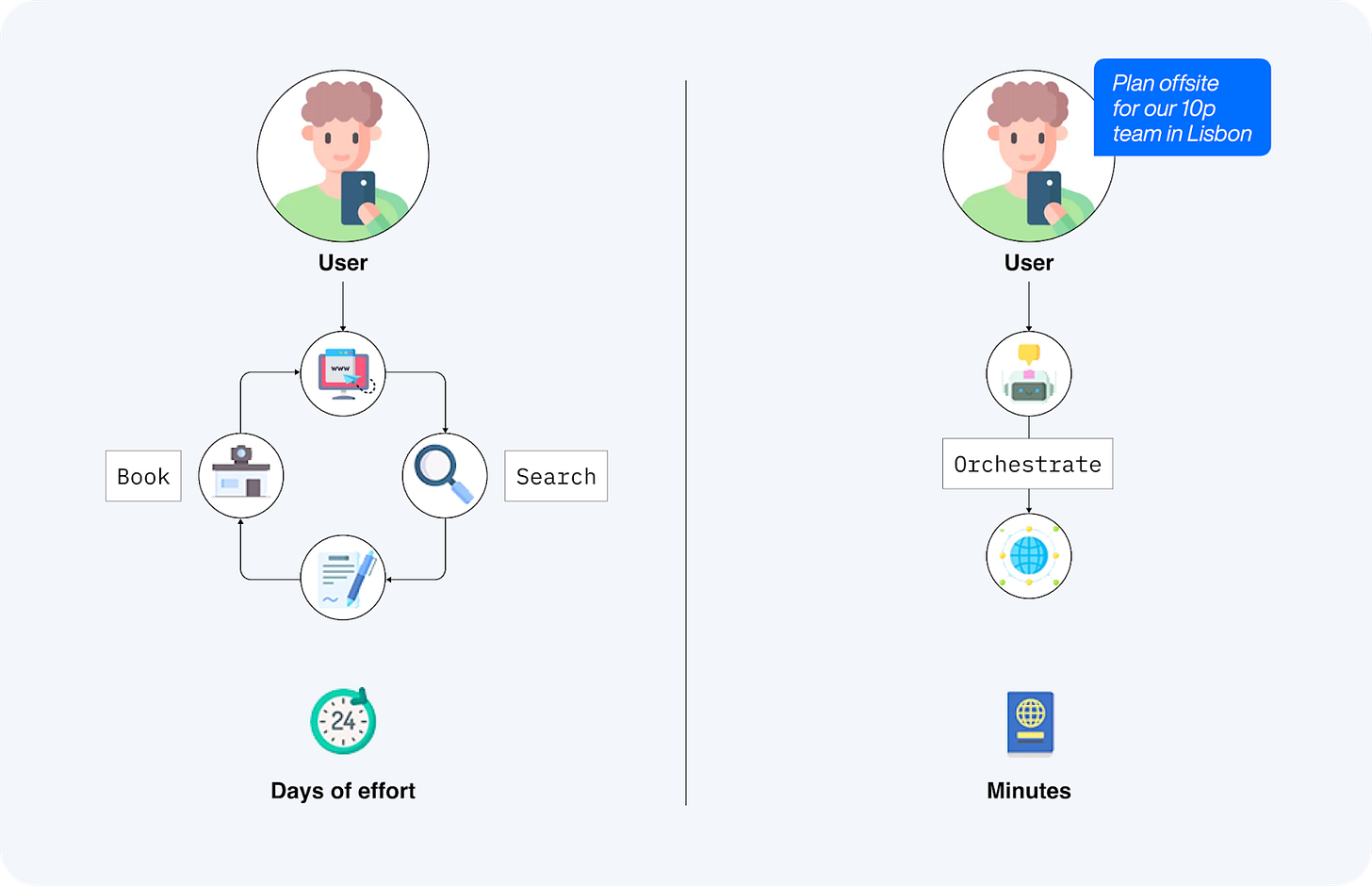

The key difference in intent-based systems is not that users want different things. It is that systems finally receive those wants directly. When intent is explicit, the user no longer has to express a goal through a sequence of actions. They simply state the outcome they want and the conditions it must satisfy. This can be as simple as a price limit, a time constraint, or a preference around risk. Once that intent is defined, the system does not wait for further instructions. It treats the intent as a problem to be solved.

This is important because explicitly defined intents also affect how the execution is carried out. Instead of a single predefined path, there are now multiple possible ways to achieve the same goal. Different routes, venues, or strategies can be evaluated without user involvement, and the system can choose the one that best fits the stated constraints. The user is no longer navigating the system. The system is navigating on the user’s behalf.

What makes this possible now is not just better interfaces but a reduction in coordination costs. Software can now cheaply evaluate many options, compare outcomes, and react in real time. Agents can operate continuously, monitor changing conditions, and adjust execution without asking for permission at every step. This was impractical when computation was expensive, systems were siloed, and execution required human intervention. Today, those limits are far lower.

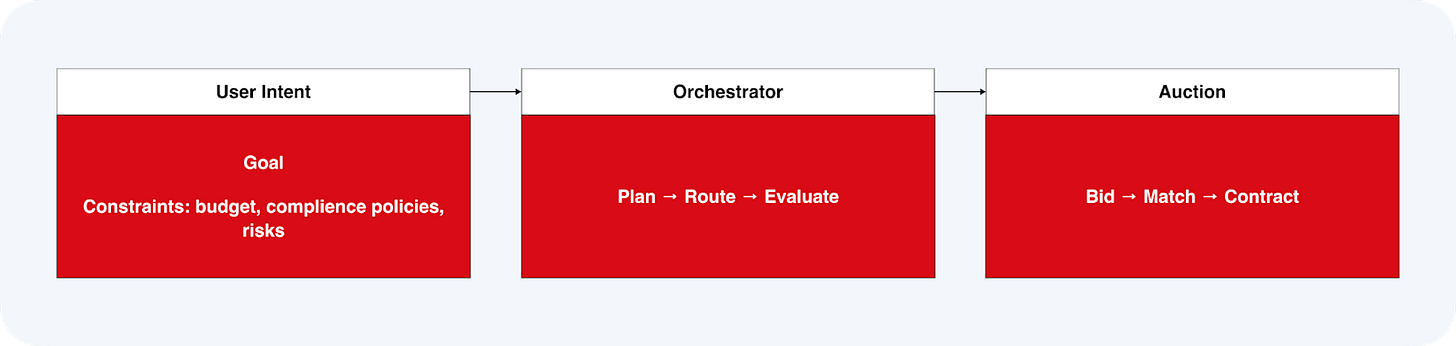

Another important change is that execution no longer needs to be owned by a single platform. Once intent is expressed in a structured way, any actor capable of fulfilling it can respond. This introduces competition at the execution layer. Different solvers, agents, or services can attempt to fulfil the same intent, and the system can select the best result based on predefined rules. The user does not need to know who executed the task, only that the outcome meets the conditions they set.

In older systems, users optimised manually by comparing options and making trade-offs themselves. In intent-based systems, optimisation moves downstream. The system compares options, absorbs complexity, and presents a result. Fragmentation stops being a problem for users and becomes an input for optimisation instead. More options improve outcomes rather than making decisions harder.

When Outcomes Become the Unit of Value

In attention-driven systems, value flows to those who control demand. Platforms compete to keep users inside their interfaces because that is where monetisation happens. In intent-based systems, value shifts toward whoever fulfils outcomes most efficiently. The scarce resource is no longer attention, but reliable execution under constraints. This is a subtle but important change. It shifts competition from surface-level engagement to backend capability.

In an intent economy, users are not browsing marketplaces or navigating platforms in the traditional sense. They are broadcasting requests. That changes who has leverage. Intermediaries that exist only to guide users through flows lose importance, while infrastructure that reduces cost, risk, or latency gains importance. Execution providers compete on speed, accuracy, price, and trustworthiness, not user lock-in. Poor execution is punished quickly because users do not need to understand why something failed, they only need to see that it did. And they can simply stop sending intent in that direction.

This also changes how markets scale. In older models, complexity increased with the number of users. More users meant more support, more interfaces, and more decision-making pushed upstream. In intent-based systems, complexity grows with infrastructure instead. Users stay simple, and the system absorbs the mess for them. This makes it easier to serve non-expert users without dumbing down the system. Power users and sophisticated infrastructure coexist, but the burden of coordination no longer sits with the person making the request.

This also lowers switching costs. When users are not locked into workflows or interfaces but simply state their intent, they are free to send that intent anywhere. Execution providers cannot rely on inertia or habit. They must compete continuously. This creates pressure to standardise intent formats, verification mechanisms, and settlement layers, as compatibility increases the size of the execution market. Over time, this pushes systems toward greater openness.

At a broader level, an intent economy changes what “using the internet” feels like. Users stop navigating systems and start issuing requests. Many interactions that previously required attention, judgment, and repeated decision-making can be collapsed into a single step. Users decide outcomes and constraints. Systems compete to do the rest. This is why the intent economy is not limited to crypto or finance. Those domains surface the mechanics clearly because execution is expensive and mistakes are visible. But the same structure applies anywhere coordination costs are high: commerce, logistics, scheduling, procurement, information retrieval, and eventually, everyday digital tasks. Wherever outcomes matter more than processes, intent-based systems outperform workflow-based ones.

That was all for today. See you next Sunday.

Until then, stay curious!

Vaidik

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.