Hello,

The year has started with significant events for crypto. The renewed tariff war between the U.S. and the European Union has once again brought uncertainty to the forefront. This was followed by a wave of sky-high liquidations in the past week.

Tariffs weren’t the only sour note to start the year. A couple of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) in the past week also gave us enough reason to revisit the crypto community’s darling topic from almost a decade ago.

Those who remember the history might believe that crypto has outgrown the 2017 ICO era. Although a lot has changed about ICOs from that time, last week’s two ICOs raised many important questions. Some old, some new.

Both Trove and Ranger saw oversubscribed demand for their ICOs, but without the aura of 2017’s Telegram-style countdowns. Still, the way these events unfolded reminded the community of the importance of fairness in the allocation process.

In today’s story, I delved into what TROVE and RNGR’s launches tell us about how ICOs are evolving and investors’ trust mechanism in the allocation process.

On to the story,

Prathik

Trove’s ICO, the more recent of the two, ran from January 8 to January 11 and raised over $11.5 million by the end of the period. That’s over 4.5 times the original $2.5 million target. The oversubscription was a clear sign of investors’ support and belief in the project, which was pitched as a perpetual exchange.

Trove had pitched to build on Hyperliquid by benefitting from the ecosystem’s perpetual infrastructure and community. However, just days after raising the funds and before the token generation event (TGE), Trove took a U-turn and announced it would launch on Solana, not Hyperliquid. Suddenly, people who had bought into the pitch on the back of Hyperliquid’s reputation felt betrayed.

This move unsettled investors and created confusion. The chaos compounded when another detail came into investors’ scrutiny. Trove said it would retain approximately $9.4 million of the funds raised for a redesigned plan and refund only the remaining few million dollars. That came as another red flag.

Eventually, Trove responded. It had to.

“We are not taking the money and running,” it said in a statement on X.

The team insisted that the project was still focused on building, and that only how they moved forward had changed.

Even without making assumptions, one thing is crystal clear: it is difficult to imagine that the contributors were not framed in an unfair, retroactive manner. While funds were committed to one ecosystem - Hyperliquid, one technical path and one implied risk profile, the revised plan asked them to absorb a different set of assumptions without reopening the terms of participation.

It is like changing the rules of the game for one player after they have started playing.

But by then, the damage was done, and the market punished the loss of confidence. Within 24 hours of going live, the TROVE token crashed by over 75%, wiping out most of its implied valuation.

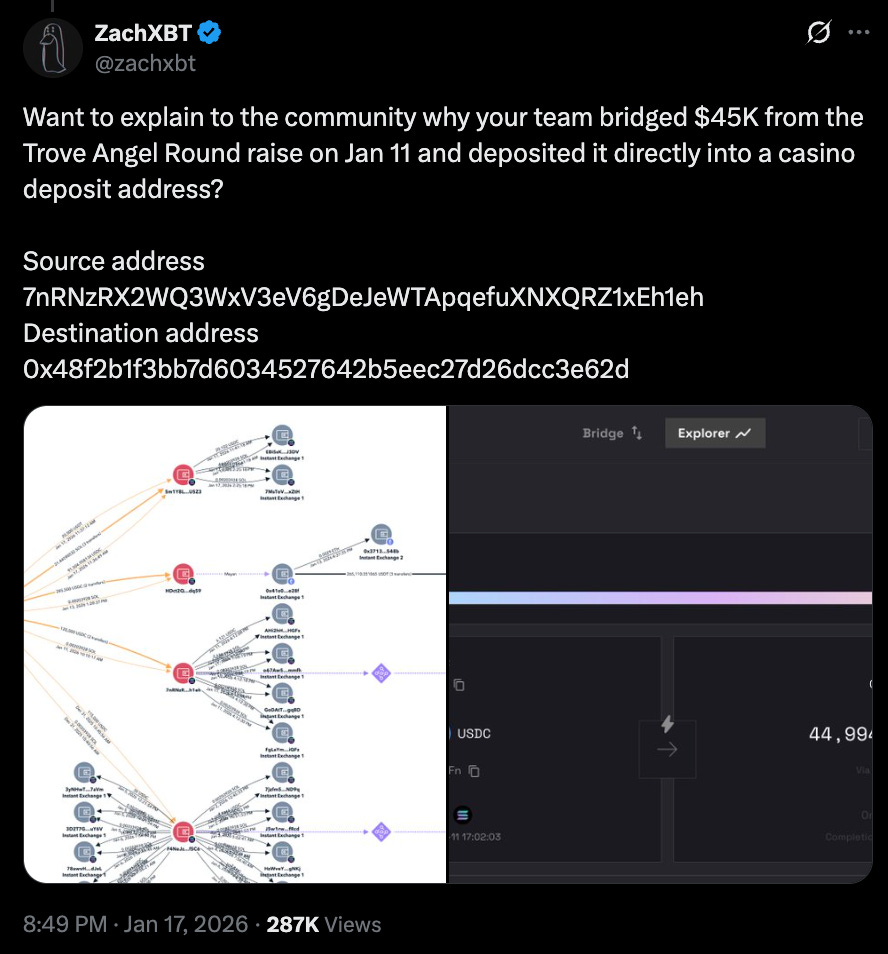

Some in the community went beyond gut feeling and began dissecting on-chain movements. Crypto sleuth ZachXBT flagged transactions where about $45,000 USDC from angel round funds ended up on platforms like prediction markets and even at a casino-linked address.

Whether it was a sloppy accounting mistake, poor fund management, or an actual red flag is still up for debate. Many users criticised the refund process, pointing out that only a fraction of those owed refunds received them on time.

Amid all this, Trove’s statement fell short of reassuring the investors who felt betrayed. While it emphasised the continuation of the project, a perpetual exchange on Solana, it did not adequately address the economic concerns raised by the pivot. It did not give a revised breakdown of how it planned to deploy and govern the retained funds. It gave no additional clarity on the refund roadmap.

Although no conclusive evidence linked the pivot to the team’s misconduct, the episode shows that once trust in the fundraising process weakens, every data point is more likely to be interpreted sceptically.

What makes this episode seem shakier is the way the team handled its discretion after the fundraiser concluded.

Oversubscription effectively transferred control of both capital and narrative to the builders. Once the team pivoted, contributors had little recourse beyond secondary-market exits or public pressure.

In some ways, Trove’s ICO resembled many from earlier cycles. While the mechanics were cleaner, and the infrastructure seemed more mature. The problem that persisted across both cycles was the trust factor, and the fact that investors still had to trust the team’s judgment, rather than having a clear procedure to fall back on.

Ranger’s ICO, which took place just days earlier, provides an important contrast.

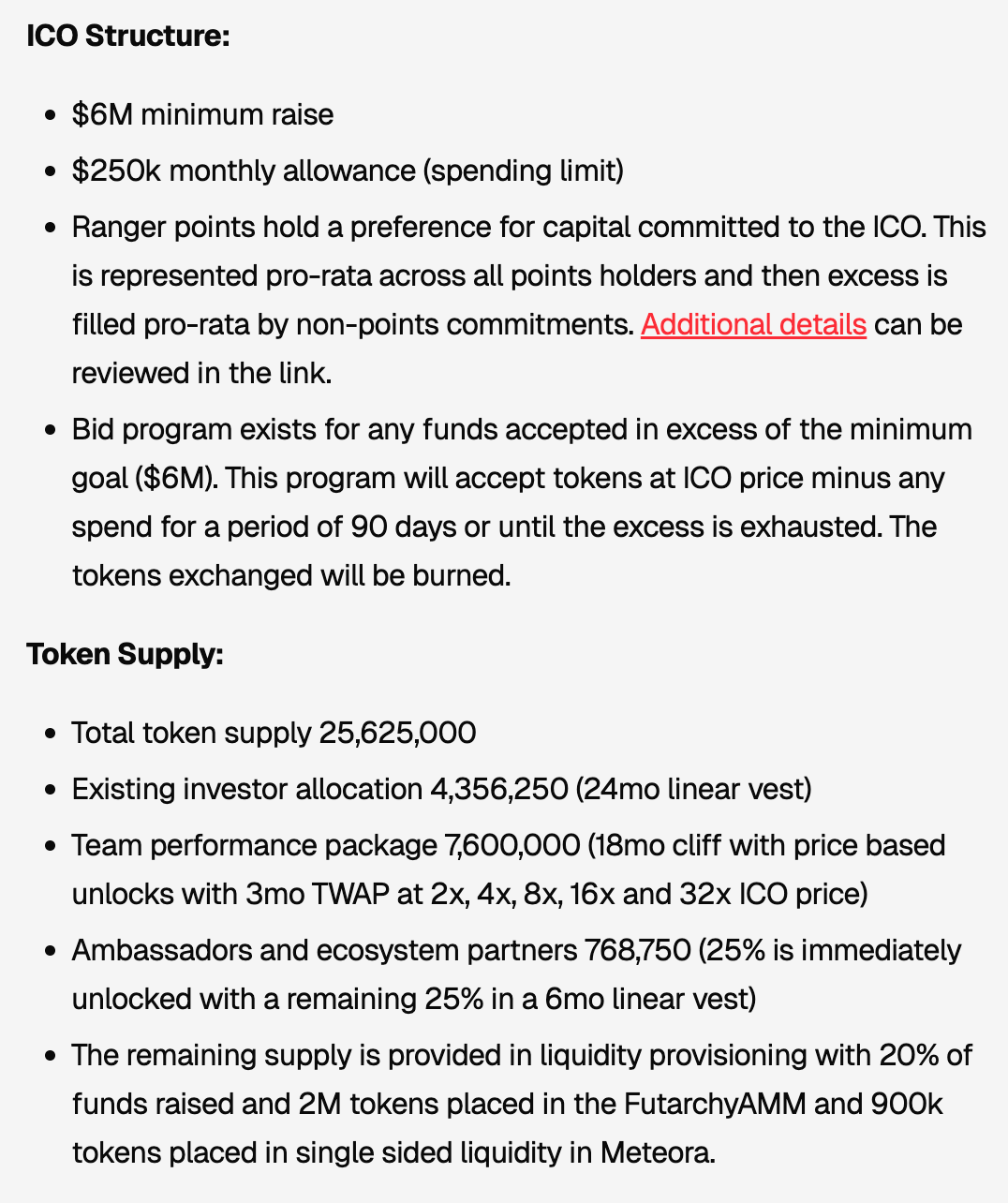

Ranger’s coin offering ran from January 6 to 10 on MetaDAO, a platform that requires teams to predefine key fundraising and allocation rules before the sale begins. Once live, those rules cannot be altered by the team.

Ranger sought a minimum raise of $6 million and sold roughly 39% of its total token supply through a public offering. Like Trove, the offer was oversubscribed. But MetaDAO’s constraints meant that the team preempted an oversubscription and accounted for it upfront, unlike in Trove’s case.

When the offering was oversubscribed, the proceeds from the sale were placed in a treasury governed by token holders. MetaDAO’s rules also cap the team’s access to the treasury at a fixed monthly stipend of $250,000.

Even the allocation structure was more clearly defined. Public ICO participants received full liquidity at the token generation event, while pre-ICO investors faced a 24-month linear vesting period. A large portion of tokens allocated to the team would only unlock if the RNGR token achieved specific price milestones. These milestones, such as 2x, 4x, 8x, 16x, and 32x the ICO price, would be measured using a three-month time-weighted average, with a minimum 18-month cliff before any unlocks could occur.

These measures show that the team embedded constraints into the fundraising structure itself, rather than expecting contributors to rely on post-raise discretion. Control over capital was partially deferred to governance rules, while any upside for the team was tied to long-term market performance, protecting contributors from launch-day rug pulls.

Still, there are concerns about fairness.

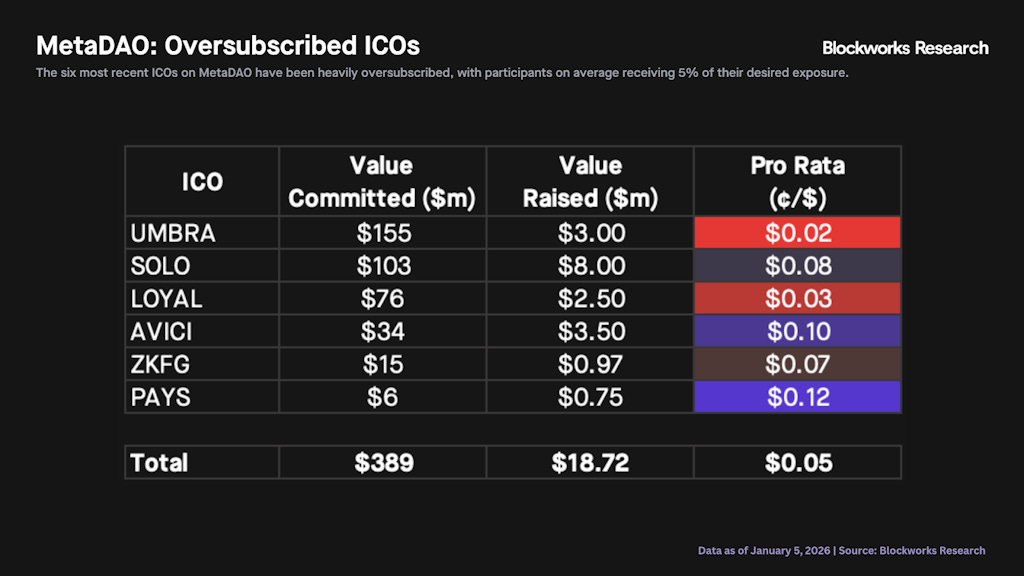

Like many modern ICOs, Ranger used a pro-rata allocation model to distribute tokens in an oversubscribed sale. This means everyone should be allotted tokens proportionate to their capital commitment. At least, in theory. However, Blockworks Research shows that this model often favours participants who can afford to overcommit capital. Smaller contributors often receive a disproportionate allotment.

But there’s no easy way out of this.

Ranger tried to address this by reserving a separate allocation bucket for those who had engaged with the ecosystem prior to the sale. This softens the impact but doesn’t completely eliminate the dilemma of choosing between broad access to tokens and material ownership.

Trove and Ranger together show that ICOs have remained constrained almost a decade after they first blew up. The old ICO model relied heavily on Telegram announcements, narrative, and momentum.

The newer model relies on structure, including vesting schedules, a governance framework, treasury rules, and an allocation formula, to demonstrate its restraint. These tools are often mandated by platforms such as MetaDAO and help limit the launching team’s discretion. However, these tools only reduce risks, but don’t remove them altogether.

These episodes raise crucial questions that teams need to address in every ICO moving forward: ‘Who decides when teams can change plans?’ ‘Who controls the capital once it is raised?’ ‘What mechanisms exist for contributors when expectations are not met?’

What happened in Trove’s case needs corrections, nevertheless. Swapping the chain on which it planned to launch its project cannot be an overnight decision. The best way to undo the damage here is for Trove to do right by its contributors. In this case, it could mean returning the funds in full and re-running the sale under revised assumptions.

Despite it being the best way forward, Trove will have its work cut out to achieve that. Capital may already have been deployed, operational costs may have been incurred, and partial refunds may have been issued. Reversing at this stage could introduce legal, logistical and reputational complications. But these are the costs of undoing the messy part that led to this.

How Trove decides to move here could set a precedent for this year’s upcoming ICOs. The offerings are returning to a much more cautious market, where contributors no longer misinterpret oversubscription as alignment or confuse participation with protection from fundraisers. Only a well-rounded system can provide a trustworthy, if not foolproof, fundraising experience.

That’s all for this week’s deep dive. I will be back with the next one.

Until then, stay curious,

Prathik

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.