In the 1960s, credit cards were a mess. Banks across America were trying to build their own payment networks, but each one was siloed. If you had a card from Bank of America, you could only use it at merchants who had agreements with Bank of America. And when banks tried to scale beyond their own banks, all card payments hit the underlying interbank settlement problem.

If a merchant accepted cards issued by a different bank than theirs, the transaction had to be settled via their old cheque based settlement system. The more banks that joined, the more problems it created in settlements.

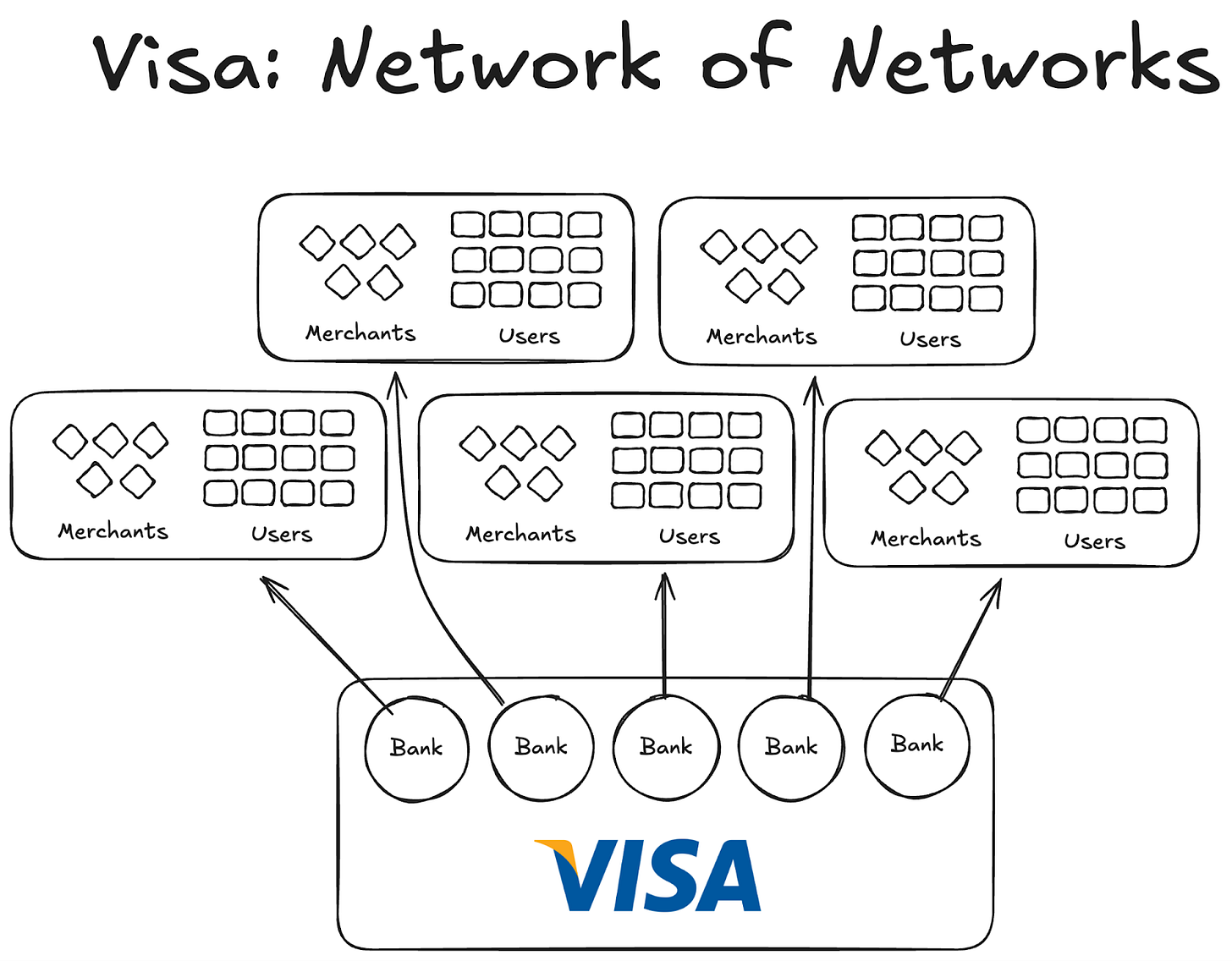

Then came Visa. While the tech it introduced definitely played a huge role in the card payment revolution, the more important win was in how it scaled universally, and somehow got banks globally to join its network. Today almost every bank across the globe is part of the Visa network.

While it feels very normal today, imagine convincing initial thousand banks both in and outside the US why it made sense to be in a collaborative agreement and not launch their own network, and you’ll start to realise the scale of this.

By 1980, Visa had become the dominant payment network, and Visa’s network processed about 60% of US credit card sales. Current operations span over 200 countries.

The key wasn’t better technology or more capital. It was the structure: a model that aligned incentives, distributed ownership, and created compounding network effects.

Today, stablecoins face the exact same fragmentation problem. And the solution might be the same playbook Visa used fifty years ago.

Experiments Before Visa

The other companies before Visa could not take off.

American Express (AMEX) tried scaling its credit card as an independent bank, but it scaled only as long as new merchants joined its banking network. On the other hand we had BankAmericard, where Bank of America owned the Credit Card network and other banks were only using its network effects and brand value.

While AMEX had to go to each merchant and user separately and get them to make an account with their bank, Visa scaled by onboarding banks itself, each bank that joined the Visa cooperation network, automatically onboarded thousands of new customers and hundreds of new merchants.

On the other hand, BankAmericard faced issues with its infrastructure. They did not know how to efficiently settle card transactions that were happening from one consumer bank account to a different merchant bank account. There was no efficient settlement system between them.

The more banks they added, the more that problem grew. Thus, Visa came into being.

Visa’s Four Pillars of Network Effects

What we know from Visa’s story is 2-3 important things that led to its compounding network effects:

It benefited by being an independent third party. To ensure that no bank would feel a threat of competition – Visa was designed as a co-operative independent organisation. Visa wasn’t competing for the distribution pie; individual banks were.

It gave the joining banks the incentive to own the pie. Each bank would be entitled to a share of the overall profit, equivalent to the share of the total transaction volume it processed.

The individual banks had a say in the network functions. Visa rules and changes always had to go through the vote of all the banks involved, with 80% as the necessary threshold to pass.

Visa had an exclusivity clause with each bank (at least initially); whoever joined the co-op would only use the Visa card and network and couldn’t be part of other networks—thus, to interact with a Visa bank, you need to be part of its network too.

When Dee Hock, Visa’s founder, was parading around the US to ask banks to join the Visa network, to each of them, he had to convince them how joining the network was more beneficial than them starting their own Credit Card network.

He had to explain how joining Visa would mean more users and more merchants on a single network, which would compound and enable more digital transactions globally, bringing more money to everyone involved. And how if they make their own CC network, they would only limit themselves to a very small pie of users.

Lesson for the Stablecoins

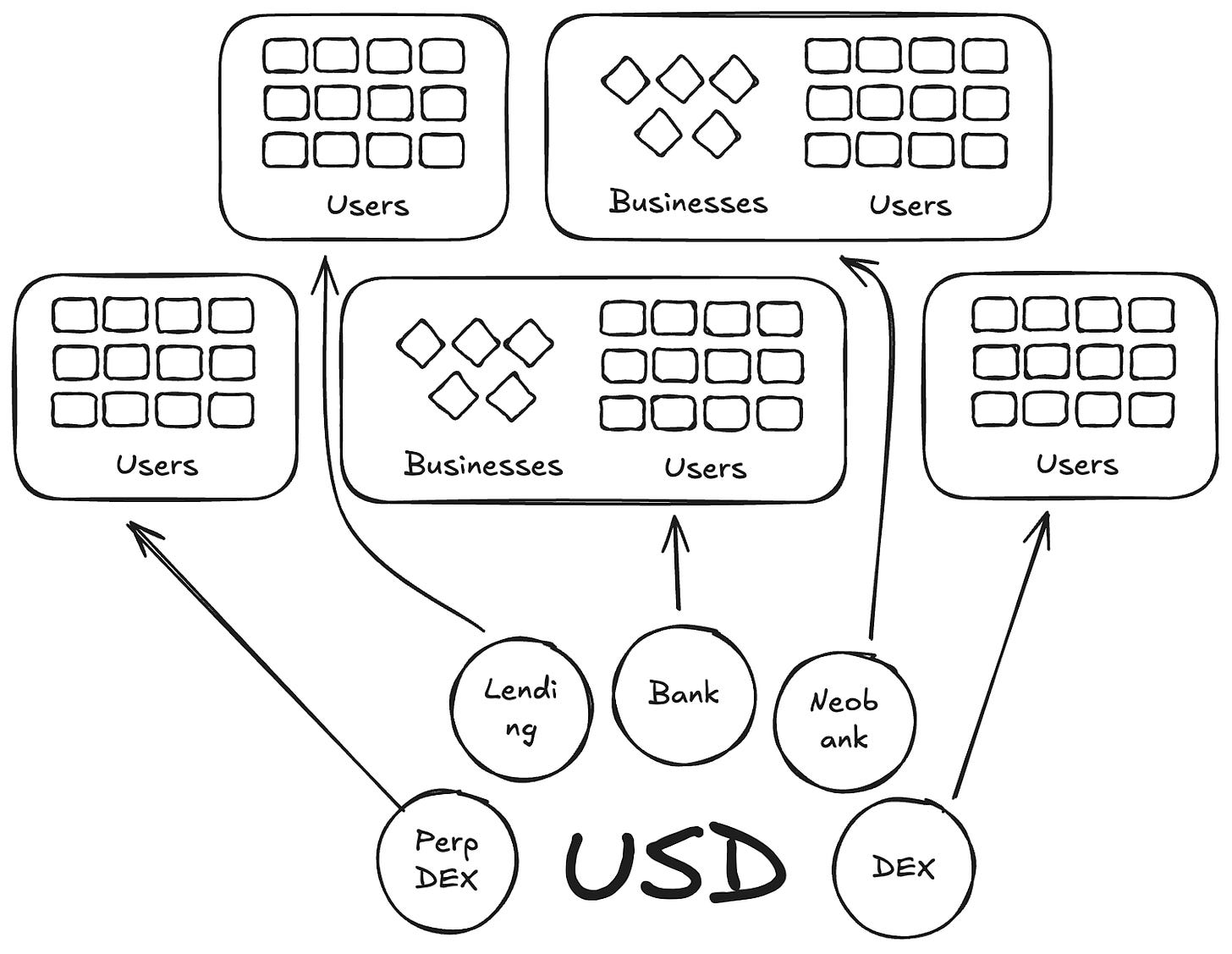

In a way, Anchorage Digital and other companies enabling stablecoin as a service today, are repeating the story of BankAmericard for stablecoins. They are offering the underlying infrastructure of building the coin to new issuers, while the liquidity just keeps on fragmenting in new tickers.

There are more than 300 stablecoins already live on Defillama today. And each new ticker created is restricted to its own ecosystem. And thus, the network effect needed to take any of them mainstream would never play out.

Why do we need more coins with new tickers when the same assets are backing them?

In our Visa story, these are like the BankAmericards. Ethena, Anchorage Digital, M0 or Bridge. Each one allows a protocol to come and issue its own stablecoin, only fragmenting the industry in the process.

Ethena is another such protocol, which allows yield passage and white-labeling of its stablecoin. Like MegaETH did with USDm—where they issued it via the instruments used to back USDtb.

However, the model fails. It only fragments the ecosystem.

In the case of credit cards, separate bank branding didn’t matter as it didn’t create any friction in user-to-merchant payments. The underlying issuing and payment layer was always Visa.

However, for stablecoins, the same is not true. Each different ticker means infinitely more liquidity pools.

A merchant, or in this case, an app or a protocol, won’t add all the individual stablecoins issued by M0 or Bridge to its list of accepted stablecoins. It’ll add them based on their liquidity in the open market; whatever coin has more holders and liquidity should ideally be accepted, the rest won’t.

The Path Forward: A Visa Model for Stablecoins

We need independent parties managing stablecoins for different groups of backing assets. The distributors and apps that like those backing assets should be able to join the co-op and take the reserve yield for themselves. While being allowed governance rights to vote and decide the direction of the stablecoin they choose.

This would be an exceptional model, network effects-wise. As more and more issuers and protocols join the same coin, it’ll enable the widespread adoption of a ticker that keeps the yield in-house, instead of one that pockets and doesn’t pass it along.

That’s it for this week’s analysis. I’ll see you next week.

Until then, stay sharp,

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.