Trading Uranium On-Chain ⛏️

Bringing one of the world’s most inaccessible commodities to blockchain

Hello,

Uranium fuels 400+ nuclear reactors worldwide and accounts for nearly 10% of global electricity generation. However, it remains largely invisible in the market. There is no widely referenced futures contract, no continuous trading venue, and no clear public signal for where prices stand at any given moment. Investors who follow commodities closely often struggle to determine how uranium is priced or where that pricing actually occurs.

This lack of transparency exists because uranium is not traded in open markets by default. The majority of the global supply is sold under long-term contracts negotiated directly between utilities and producers, often years in advance of delivery. These contracts dominate the volume and dictate pricing for most of the market. Spot transactions occur at the margins, typically when utilities require additional supply or inventories are low, but they are irregular and thin.

This is what has led to recent attempts to represent uranium exposure on-chain. Rather than changing how uranium is produced or consumed, these efforts focus on how claims to physical uranium can be held and transferred.

In this article, I will examine what that shift enables and where it encounters hard limits, with a closer look at projects such as xU308 that aim to make uranium more tradable.

Let’s dive in!

How the Uranium Market Moves

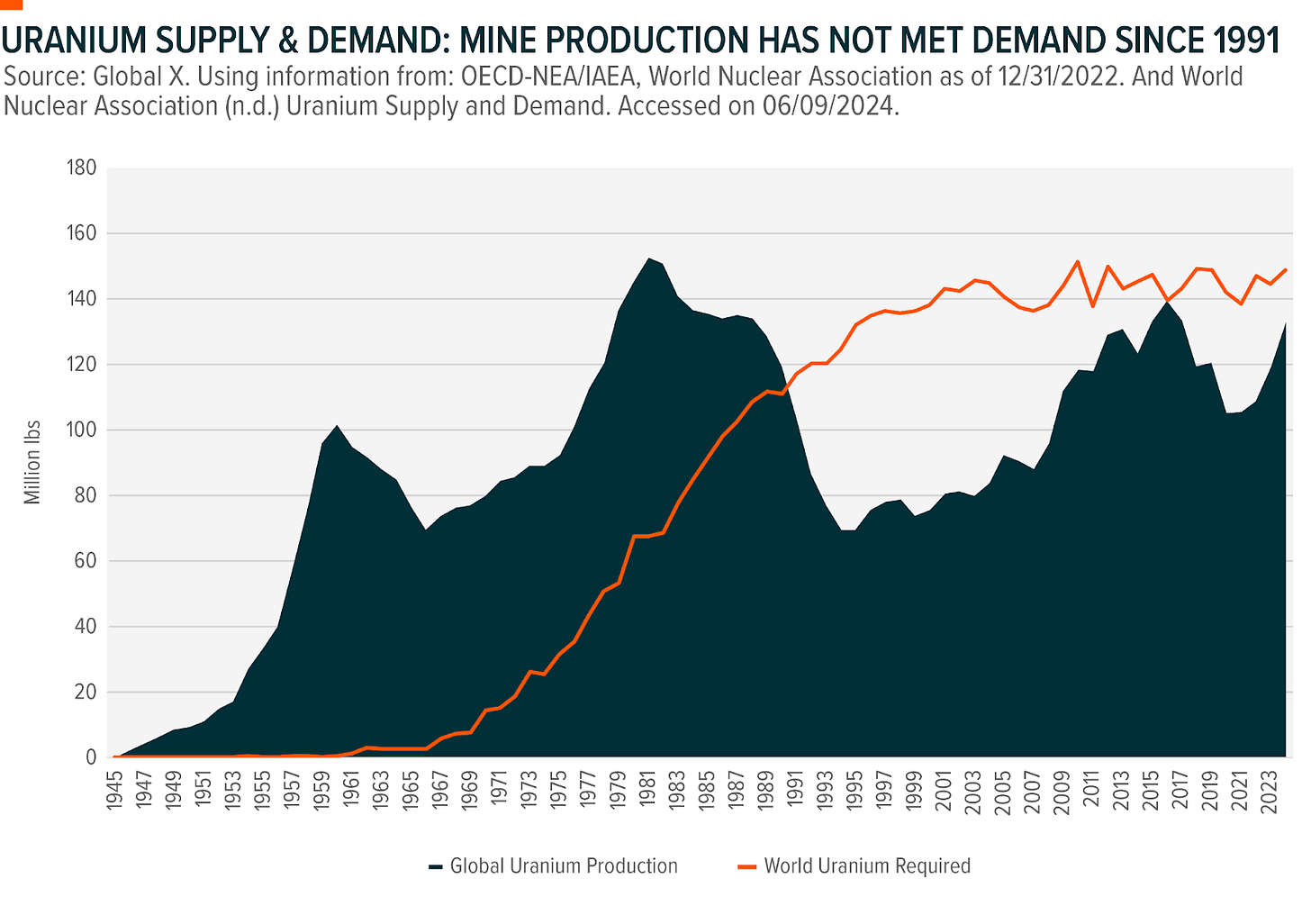

Once you step into the uranium market, the first thing that becomes clear is that buying does not happen continuously. Utilities plan their fuel requirements well in advance, but actual purchases are clustered. Long stretches pass with little activity, followed by short windows where several utilities return to the market at the same time to secure supply.

This pattern shapes how prices move. Uranium prices often remain unchanged for months or even years because utilities are not active buyers between these cycles. When purchasing resumes, it usually occurs under time pressure. At that point, utilities are focused on securing supply. When several buyers return to the market simultaneously, prices can move quickly.

Inventory plays a central role in this behaviour. Utilities typically hold several years of forward fuel coverage, which allows them to stay out of the market for extended periods. As long as their coverage stays above internal thresholds, there is little urgency to transact. Once inventories fall below those levels, buying becomes unavoidable, and availability matters more than the current price.

But supply cannot move at the same pace during this period. Opening a new uranium mine or bringing an idled one back online takes years, once permitting, financing, and regulatory approvals are factored in. So, when demand resumes, supply cannot be scaled up to match in the short term. The market adjusts by drawing down existing inventories, and prices rise until new projects finally make sense, even though any new production shows up long after the buying pressure has already peaked.

Why Access Has Always Been the Problem

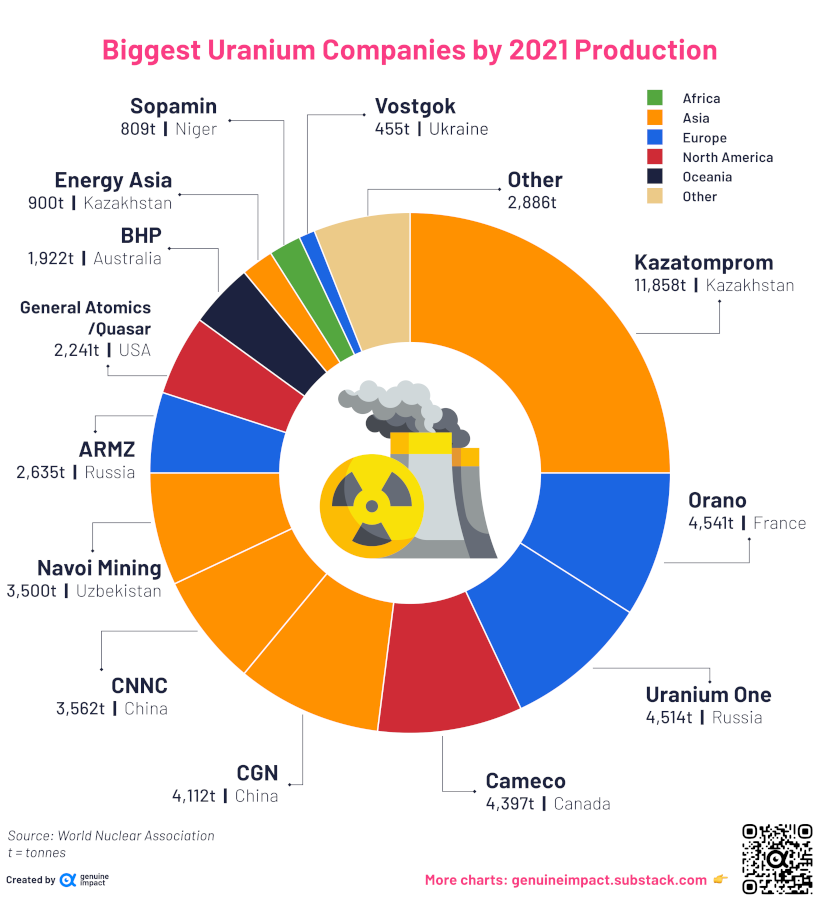

Given the structure of the uranium market, it has never been easy for anyone outside utilities and producers to gain direct exposure. Long-term contracts are negotiated privately and are intended for fuel procurement, not for trading or investment. Spot transactions exist, but they are limited, regulated, and irregular. For most participants, there has simply been no clean way to buy or sell uranium.

As a result, exposure has often come through workarounds. The most common method is by investing in uranium mining stocks. Investors buy producers or developers as a proxy for uranium prices, even though these businesses are affected by many factors beyond the commodity itself. Operating issues, financing cycles, jurisdictional risks, and management decisions often matter as much as, or more than, the price of uranium. In some cycles, equities amplify uranium price movements, while in others, they diverge completely.

There have also been attempts to offer more direct exposure through funds and vehicles that purchase and store physical uranium. These come closer to tracking the commodity, but they remain slow and restrictive. Access is limited, transactions are infrequent, and ownership changes hands through fund structures rather than through direct uranium transfers. What ties these approaches together is that they share the same constraints discussed earlier. Storage remains centralised and regulated. Transfers remain slow. Pricing still updates in steps, not continuously. The structure remains the same but is presented in different forms to provide access.

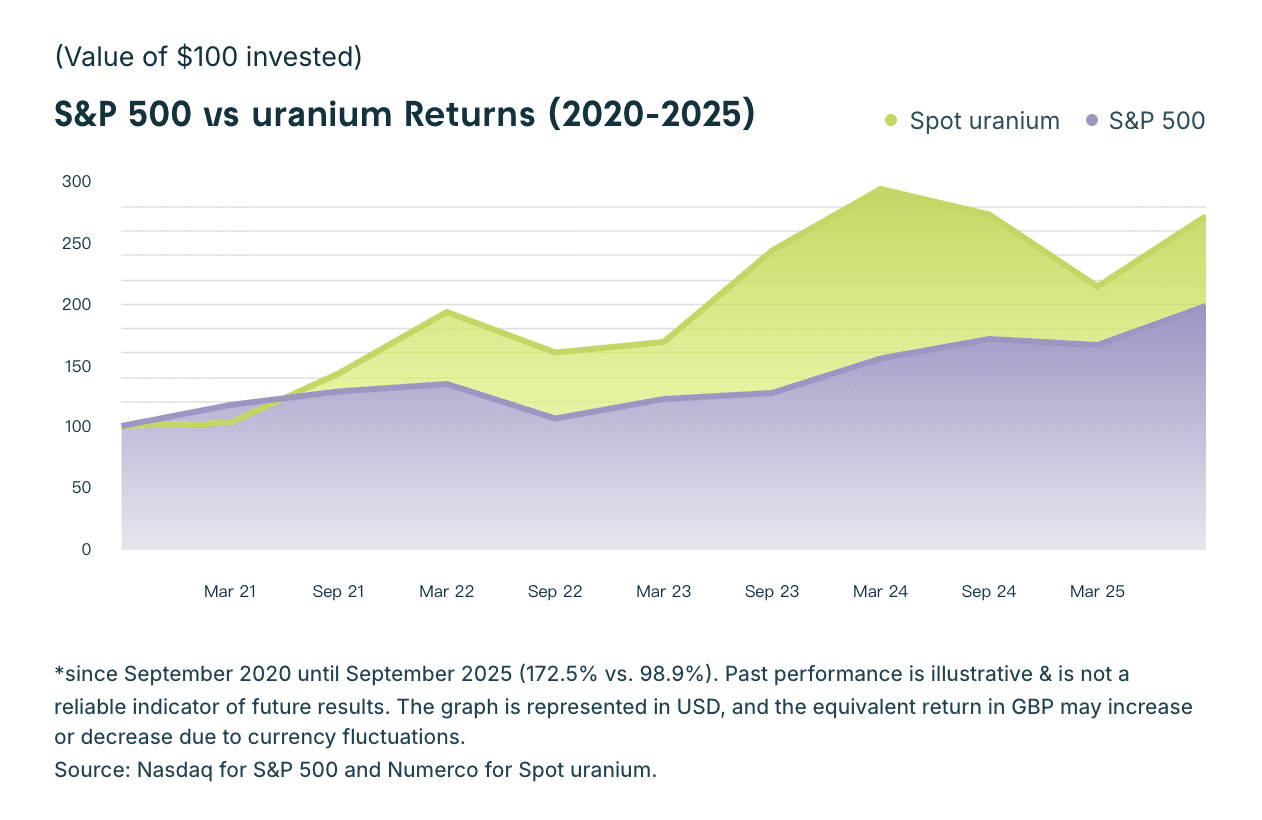

As interest in uranium has grown, these limitations have become critical. Investors seeking exposure now want something closer to the commodity than mining equities, yet more flexible than traditional physical vehicles. They desire clearer pricing, smaller position sizes, and the ability to move exposure without waiting for contract cycles or fund windows.

Trading Uranium On-Chain?

One idea that significantly expands participation in the uranium market is to make it tradable on-chain. This means turning exposure to physical uranium into something that can be held and transferred digitally, without negotiating contracts, arranging storage, or relying on fund structures. If that works, uranium exposure would no longer be restricted to utilities, producers, or a narrow set of institutions. Access could be widened to anyone who meets regulatory requirements.

I know this idea might sound counterintuitive. Uranium is one of the most tightly regulated commodities in the world. Physical handling is controlled, storage is licensed, and ownership is closely monitored. The market was never designed for frequent transfers or broad participation, and these constraints were intentional.

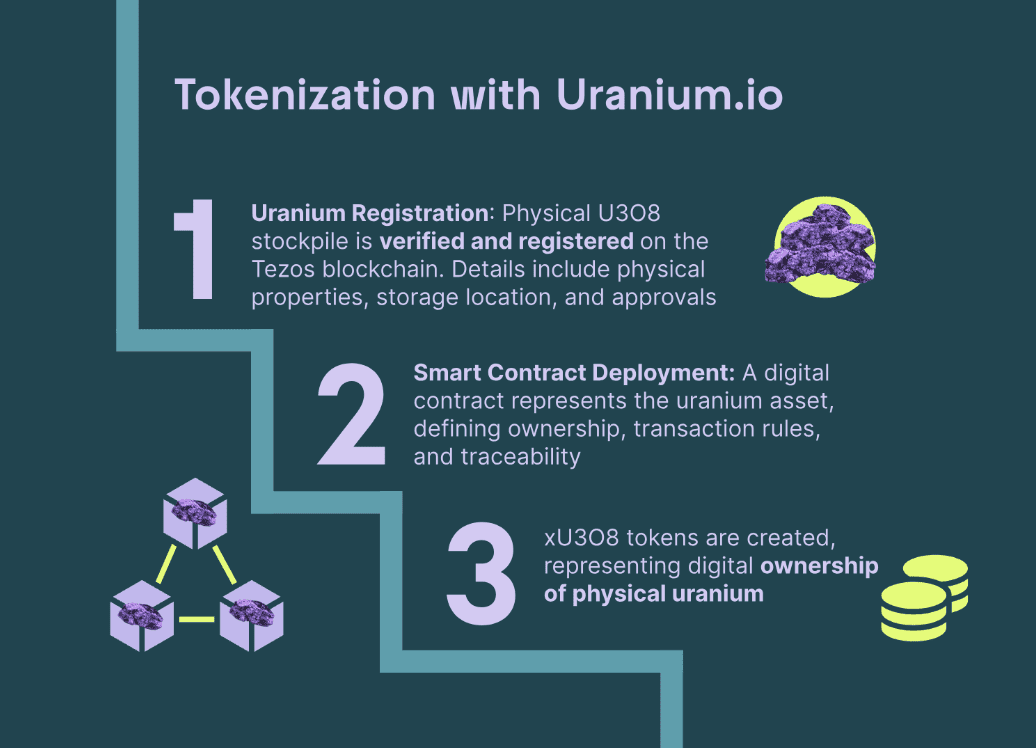

That constraint is exactly what projects working on on-chain uranium are trying to solve for. The physical material does not move. Uranium remains in licensed storage facilities under regulatory oversight, with custody and auditing conducted in physical facilities, off-chain. What changes is how ownership is recorded and transferred. Instead of access being tied to bespoke contracts or slow-fund mechanisms, claims on already-stored uranium are expressed in standardised units that can be transferred digitally.

This model is used by protocols like xU308. Physical U₃O₈ is held with approved custodians and independently verified. Each unit represents a specific quantity of uranium. When ownership changes, the uranium stays exactly where it is. Storage, compliance, and oversight remain unchanged. Only the ownership record is updated.

In practical terms, this eliminates several layers of friction that have traditionally limited participation. Exposure can be taken in smaller sizes. Ownership can change without waiting for fund windows or renegotiating contracts. Pricing becomes easier to observe because transactions happen in a consistent format rather than through one-off deals. Uranium does not suddenly become liquid or speculative, but it does become more accessible.

The timing here matters a lot.

Uranium supply is slow to expand, inventories are finite, and new production takes years to arrive. As access improves, price signals are likely to emerge earlier in the cycle, not because fundamentals change, but because more participants can see and respond to tightening conditions.

On-chain trading does not solve uranium’s scarcity. But it surely changes how that scarcity is reflected in the market, and who gets exposure to it.

That’s all for today. See you next weekend!

Until then, stay curious!

Vaidik

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.