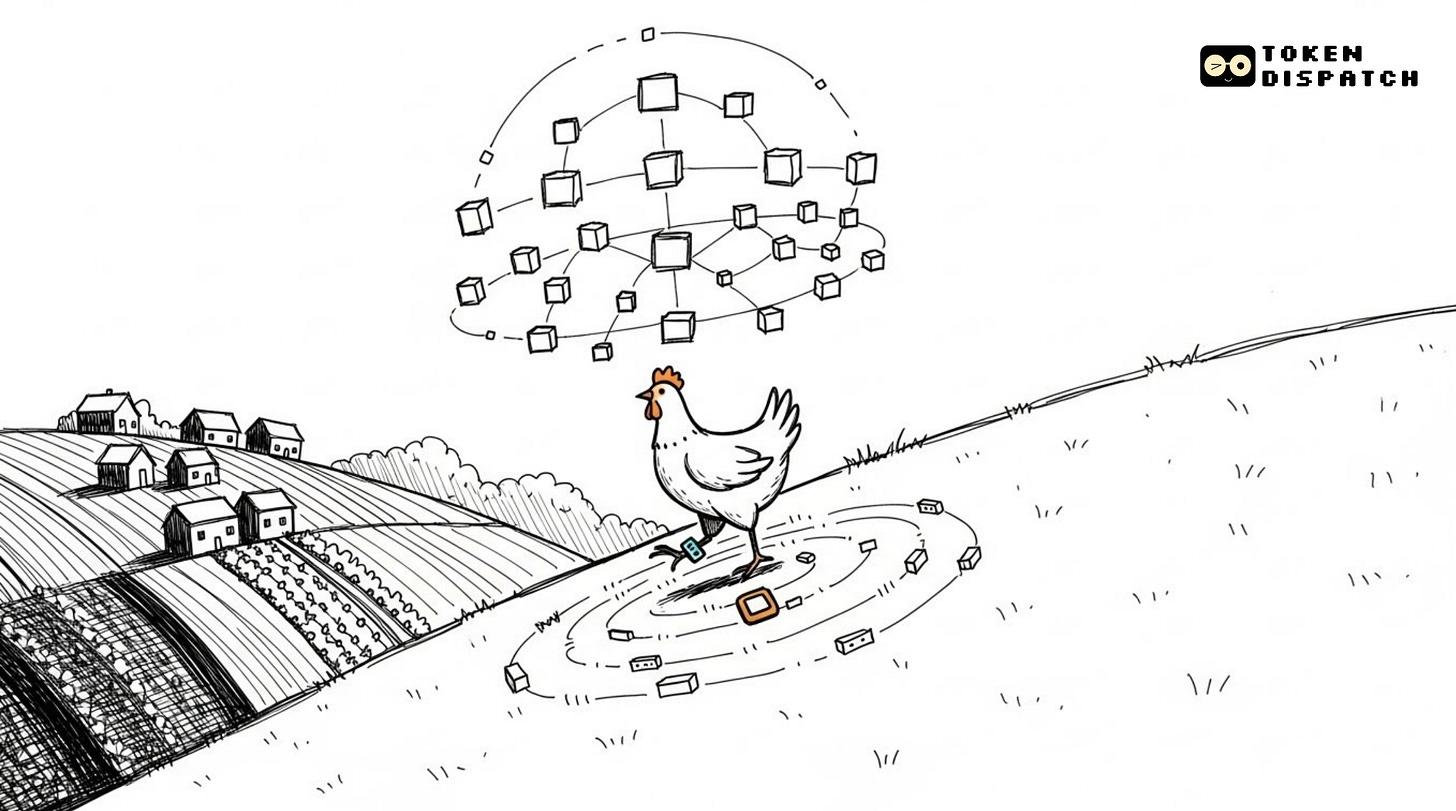

Trustless Chickens 🐔

Blockchain chickens, rural China and the part of “real world use cases” we usually skip.

I spent the last few years saying “Blockchain has real use cases,” the same way you might say “I drink enough water” or “I’ll sleep earlier next week.”

It is technically true, but you do not examine it too closely. Somewhere on every deck, there is the same little list, which includes supply chain, provenance, food safety, luxury goods authentication, and anti-counterfeit. It sits there like parsley on the plate. Decorative proof that this is not just memes and leverage.

What I had not done, until reading this book, was really look at what it means for a living thing to become a line item on a distributed ledger. Not the marketing version, where “farm to table” becomes an animated arrow in a pitch video, but the actual story of a bird, a village, and a country trying to eat without poisoning itself.

Crypto has this strange habit of talking about the physical world as if it were a distant relative. We say “on-chain” and “off-chain” like dimensions in a sci-fi novel, then spend all our time optimising the on-chain dimension. We obsess over gas costs and oracle design while treating soil, bodies, labour, and fear as background texture. The “real world asset” is always the chicken, never the human anxiety that makes someone scan a QR code before dinner.

Reading Xiaowei Wang’s Blockchain Chicken Farm felt like someone quietly turned the camera around. The technology is still there, but it is no longer the protagonist. The protagonist is trust, or rather, the crater left behind when trust fails so badly that you start putting ankle monitors on poultry.

Polymarket: where your predictions carry weight

Bet on the future by trading shares in outcomes, elections, sports, markets, you name it. Polymarket turns collective wisdom into real-time probabilities.

Now merged with X, predictions are integrated with live social insights from Grok & X posts.

Think you know what’s coming next? Prove it.

The surface story is tidy enough to fit on a slide.

In Guizhou’s Sanqiao village, Farmer Jiang raises free-range “under-the-tree” chickens that wander around for months instead of being industrially fattened in forty five days. Each bird wears a little ankle tracker. Think poultry Fitbit, but without the wellness branding.

The data flows into an experimental blockchain run by ZhongAn Insurance through a Shanghai company called Lianmo Technology. A middle-class family in some faraway city pays around ten times the normal price, scans a QR code on the packaging, and sees the chicken’s entire life: steps, weight, photos, GPS traces. They can watch surveillance footage of their dinner walking around a hillside.

The bird arrives at the door dead, vacuum sealed, still wearing its bracelet. You can eat it while scrolling through its step count.

Yes, innovation… also paranoia as a service?

Apparently, there are people who want to make sure their chicken has been outside, walking around, and eating healthy for a few months before it shows up on their plate. Can’t relate, but good for them.

Also, it exists because the Chinese food system has been repeatedly traumatised by melamine baby formula, gutter oil, and soy sauce “enriched” with human hair. You are not really paying for “premium free range protein”. You are paying to worry a little less about what is on the plate.

Blockchain here is not solving a technology problem. It is a very expensive, wired apology for a broken social contract.

That is the first uncomfortable thing the book forces you to admit. A lot of what we call “trustless technology” is really prosthetic trust, bolted on after the original trust has been hollowed out.

Wang does something most crypto people never bother to do: she asks, Where did this whole “trustless” worldview even come from?

At a San Francisco blockchain conference, the usual cast of engineers quotes Hobbes and nods along to slides about “the tragedy of the commons”. The story is familiar. Leave humans alone with a shared resource, and they will overgraze the pasture, ruin everything, so you need hard constraints and mathematical punishment.

Follow that story back, and you end up with Garrett Hardin. A white nationalist who used fake ecology to justify eugenics and border control. His famous essay about the inevitable collapse of the commons was not just morally rotten; it was empirically wrong. Elinor Ostrom won a Nobel Prize, demonstrating that real communities can manage shared resources without degrading them.

Yet Hardin’s instinct about human nature survived the debunking and quietly embedded itself in protocol design. The foundational assumption in a lot of crypto is simple and harsh: people are selfish, coordination fails, so the safest system is one in which you never have to trust anyone.

You can see that logic in how we talk about Proof of Work and Proof of Stake. We burn energy, capital, and time to defend against hypothetical attackers. We design systems where every block is produced in a posture of flinch, as if betrayal is the default and cooperation an exception.

Once you hold that next to a blockchain chicken, it stops being a cute use case and starts to look like a mirror. The melamine scandal and a Bitcoin mine are very different phenomena, but both live downstream of the same belief: if you leave humans alone with incentives, they will poison each other for profit unless the system holds a gun to their heads.

The part that really made me put the book down was not the chickens. It was the cap table.

Farmer Jiang does not own the blockchain. He does not own the hardware, the software, the ankle bracelets, or the customer relationship. Lianmo Technology owns the equipment and the app. ZhongAn controls the chain. Urban consumers perceive the story through JD.com, WeChat mini-programs, and marketing text written in Shanghai and Beijing.

One year, Lianmo ordered six thousand chickens from him. Next, they ordered none. No warning, no explanation, just silence. The farmer is left with incomprehensible hardware and a business model that may have evaporated.

The sales pitch of blockchain is “no more middlemen”. The reality, here, is “new middlemen with better fonts”. We traded a visible chain of wholesalers and distributors for an invisible hierarchy of platform operators, insurers, protocol designers, and local officials.

On a network diagram, the system looks decentralised. On the ground, the power is exactly as centralised as the contracts, funding, and servers are.

That is the second big correction this book offers to the standard crypto myth. Putting records on a distributed database does not automatically flatten power. Ownership of the edges still matters. Whoever controls the devices, the interfaces and the flow of orders can continue to extract value from the people whose lives we describe as “onboarded.”

Crypto likes to talk about “sovereign individuals” and “self-custody”. In Jiang’s village, the only thing sovereign is the weather.

Who gets to write the fiction

Wang keeps circling one question that I cannot get out of my head now. Who lives inside fictions, and who gets paid to write them?

States write five-year plans. Companies write pitch decks and strategy docs. Protocol designers write whitepapers and governance frameworks. Investors write these. Rural villagers end up living inside all of those overlapping stories at once.

In Sanqiao, the fiction goes something like this: Blockchain will bring transparent markets to poor farmers. Data will empower them. Disintermediation will improve their margins. All of this will be achieved through neutral technology, not messy politics.

The reality is more ambivalent and more human. The project does redistribute money. Profits from chicken sales are shared among the village’s households as part of a poverty alleviation program. The village is building a vocational school. Young people talk about coming back home instead of staying permanently in factory towns. There is genuine uplift here.

At the same time, nobody in the village can audit the code that routes that uplift. They tap through interfaces someone else designed, under rules someone else set, inside a legal and technical regime so far away it might as well be in orbit.

One of the conference speakers Wang quotes describes this as a shift, not a removal, of bureaucracy. You do not get rid of administrators. You replace them with maintainers of infrastructure. Instead of arguing with a local official, you are now arguing with a smart contract whose authors live on another continent.

Crypto people like to say “code is law.” It sounds clean until you realise most of the people subject to that law never got to vote on it.

If your brain is trained by markets, it is very tempting to read Wang’s book and immediately start mapping everything to tokens.

You can almost see the inevitable seed deck. Rural provenance protocol. On-chain food safety oracle. DePIN for livestock. Chicken as a service.

We do this because that is how we decide what matters. Does it have a ticker? Does it have a chart? Does it show up in a TVL ranking? If not, it becomes a nice story about “impact” that everyone forgets by the next cycle.

The first forty-five pages of this book flipped that instinct for me. The least interesting thing is whether this project ever gets tokenised. The most interesting thing is the mismatch between what the system knows how to price and what actually holds value.

The chicken is completely financialised. It has a unit price, a QR code, and a provenance graph you can scroll through on your phone. It is plugged into a national narrative about food security and healthy consumption. That part the system understands well.

The village does not fit nearly as neatly. The clean air, the soil, and the fact that Guizhou is both “remote” in a development report and “pristine” in an eco-tourism brochure. The knowledge that lets a farmer raise birds in those hills without antibiotics. None of that sits comfortably inside a ledger.

Wang includes this small detail near the end of the chapter. When they leave, Jiang hands them a bag of oranges. He says he grew them for his family, using the blockchain chickens’ manure as fertiliser. He knows they are safe because he grew them. The most technologically advanced part of the system becomes fertiliser for something that needs no verification at all. The market knows how to price the chicken. The farmer knows how to value the orange.

Crypto is very good at turning things into collateral. It is much worse at recognising value that refuses to sit still long enough to be tokenised.

So what do we do with a blockchain chicken?

If this were a normal book review, this is where I would conclude that the book is beautifully written, tell you to go buy it, and give it four and a half stars. That feels like an insult to what it actually did to my brain.

Instead, I want to treat Jiang’s chickens as a test for our own narratives in crypto.

If you claim that blockchains “eliminate middlemen”, ask yourself who owns the ankle bracelets. If you claim that “code is law”, ask who has to live under that law without being able to read it. If you claim that we are “building trustless systems for the unbanked”, ask whether the people you are supposedly empowering even know what the word “blockchain” refers to.

I am not saying the project in Guizhou is bad. It clearly improved some people’s lives. It raised incomes, funded local infrastructure, and created options that did not exist before. That matters.

I am saying that if this is one of our favourite “real-world use cases”, we should at least be honest about what it reveals.

It shows that blockchains are very good at instrumenting mistrust. They can wrap a traumatised food system in a cocoon of data and cryptography. They can make paranoia legible to capital. What they cannot do, on their own, is repair the thing that broke trust in the first place.

It shows that “decentralisation” drawn on a whiteboard can still translate into a very familiar pyramid of control when it hits a village road.

It shows that we are building ledgers that can track every step a chicken takes, while remaining mostly blind to the lives arranged around that bird. The ledger records everything it was designed to see and almost nothing about why anyone thought this was the best we could do.

Next week, I want to follow Wang deeper into rural China. To pearl farms that feed into global luxury supply chains. To villages stitching Halloween costumes for children they will never meet. To all the places where our infrastructure meets other people’s reality.

For now, I am stuck on a simpler image: A chicken walking in circles on a mountain slope, generating data for systems it cannot comprehend, creating value it will never capture. A ledger that records its steps in perfect detail and explains almost nothing about why anyone thought this was the best we could do.

That might be the most honest description of our industry so far.

See you next week. Until then, stay curious.

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.

The "prosthetic trust" framing is sharp. Blockchains instrumenting mistrust instead of repairing it cuts through alot of the tech-solutionism we usually hear. The part about farmers getting deplatformed overnight tho really shows how ownership of the infrastrucutre matters way more than the ledger architecture.

There are those who dismiss the entire crypto industry as a scam and useless. That’s wrong. And then there are those who label even the smallest or most far-fetched use case of the technology as a game changer for humanity. That’s also wrong. This article offers a rarely seen, nuanced perspective on the industry. Thanks for publishing it!