Truth Comes Later

Prediction markets are not broken. We are just lying about what they are

There is a question we keep circling around every time prediction markets run into controversy, and yet, we never quite ask it directly.

Can prediction markets be about truth at all?

Not accuracy. Not usefulness. Not whether they beat polls, journalists, or Twitter timelines. Truth.

Prediction markets price events that have not yet occurred. They are not reporting facts. They assign probabilities to futures that remain open, contingent, and unknowable. Somewhere along the way, we began treating those probabilities as a form of truth.

For most of last year, prediction markets were enjoying their victory lap.

They beat the polls. They beat cable news. They beat pundits with PhDs and PowerPoint decks. During the 2024 US election cycle, platforms like Polymarket were quicker to reflect reality than almost every mainstream forecasting tool. That success hardened into a narrative. Prediction markets were not just accurate. They were superior. A cleaner way to aggregate truth. A more honest signal of what people really believed.

Then January happened.

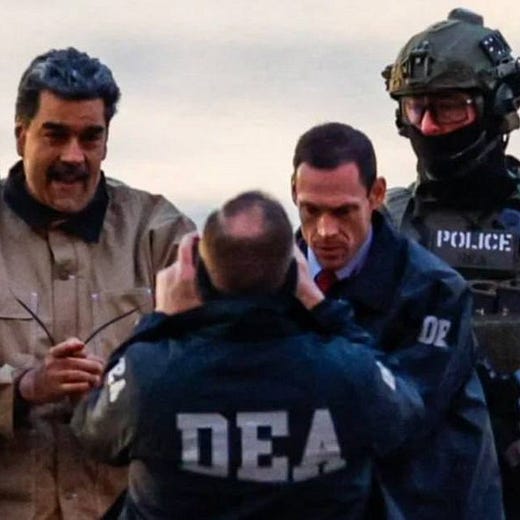

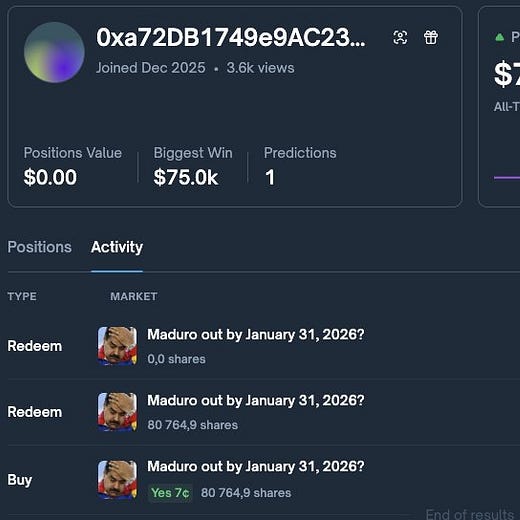

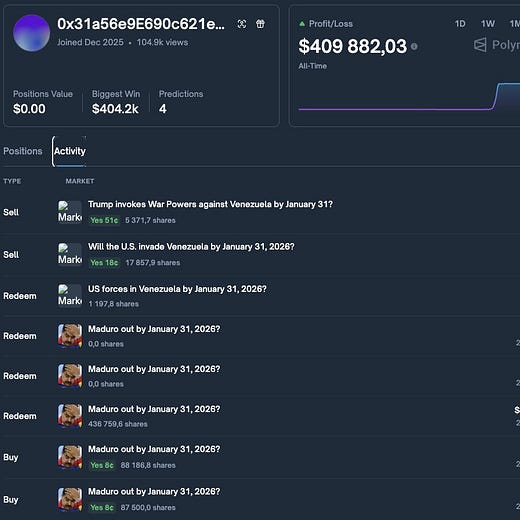

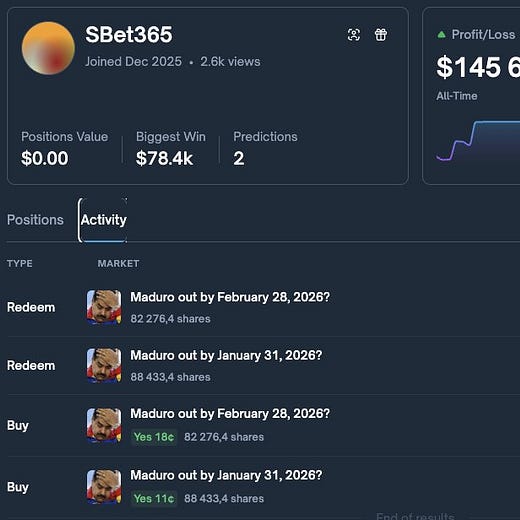

A brand new account appeared on Polymarket and placed a roughly $30,000 bet on the removal of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro by the end of the month. At the time, the market priced that outcome as highly unlikely. Single-digit probability. It looked like a bad trade.

Hours later, US forces captured Maduro and flew him to New York to face criminal charges. The account closed its position for more than $400,000.

The market was right.

That is exactly the problem.

There is a comforting story people tell about prediction markets.

Markets aggregate dispersed information. People with different perspectives put money behind their beliefs. Prices move as evidence accumulates. The crowd converges on truth.

That story assumes something important. That the information entering the market is public, noisy, and probabilistic. Polls tightening. A candidate making mistakes. A storm changing course. A company missing earnings.

The Maduro trade did not feel like that. It did not look like an inference. It looked like timing.

This is the moment where prediction markets stop feeling like clever forecasting tools and start feeling like something else entirely: a place where proximity beats insight, and where access beats interpretation.

If the market is accurate because someone knows something the rest of the world does not and cannot know, then the market is not discovering the truth. It is monetising information asymmetry.

That distinction matters more than the industry wants to admit.

Accuracy can be a red flag. Supporters of prediction markets often respond to criticism with the same line. If insiders trade, the market moves earlier, helping everyone else. Insider trading accelerates truth.

This argument sounds clean in theory, but in practice, it collapses under its own logic.

If a market becomes accurate because it contains leaked military operations, classified intelligence, or private government timelines, then it is no longer an information market in any meaningful civic sense. It becomes a shadow exchange for secrets. There is a difference between rewarding better analysis and rewarding proximity to power. Markets that blur that line eventually attract attention from regulators, not because they are inaccurate, but because they are too accurate in the wrong way.

What makes the Maduro episode so unsettling is not just the size of the payout, but the context in which these markets have exploded.

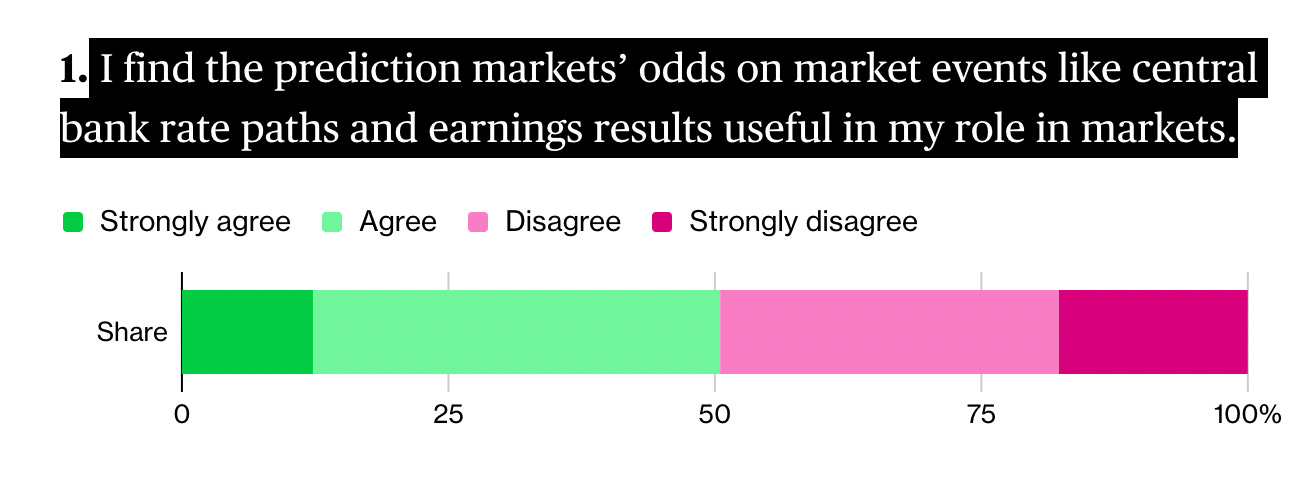

Prediction markets have gone from niche curiosities to independently financed ecosystems that Wall Street is now taking seriously. According to a December Bloomberg Markets survey, traditional traders and financial firms view prediction markets as a durable financial product with staying power, even as they acknowledge the blur between gambling and investing that these platforms expose.

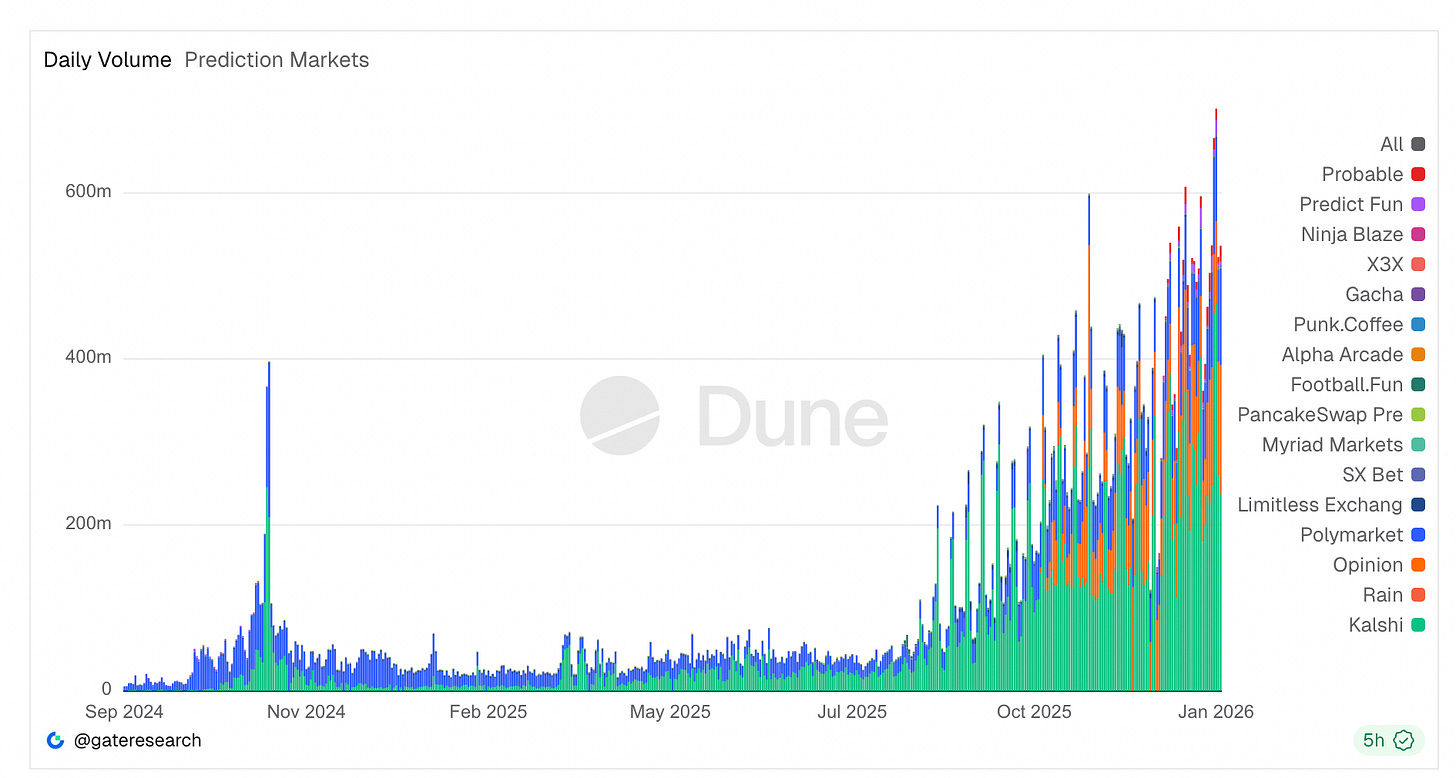

Volumes have surged. Platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket now handle billions in annual notional volume — Kalshi alone processed nearly $24 billion in 2025, with daily records being set as political and sports contracts attract liquidity at unprecedented scale.

Despite the scrutiny, daily trading activity across prediction markets has hit record highs, around $700 million. Regulated platforms like Kalshi dominate volume, while crypto native platforms remain culturally central. New terminals, aggregators, and analytics tools are popping up weekly.

This growth has drawn heavyweight financial interest as well. The owner of the New York Stock Exchange committed up to $2 billion in strategic deals to Polymarket the company at roughly $9 billion, signaling Wall Street’s belief that these markets can rival traditional trading venues.

However, this rush has collided with regulatory and ethical ambiguities. Polymarket only recently regained conditional US approval after a regulatory ban and a $1.4 million CFTC fine for earlier unregistered operations. Meanwhile, lawmakers such as Rep. Ritchie Torres have introduced bills aimed specifically at banning trading by government insiders following the Maduro payout, citing concerns that the timing of the bets looked more like a front-running opportunity than informed speculation.

And yet, despite these pressures including legal, political, and reputational participation has not declined. In fact, prediction markets are expanding into arenas from sports parlays to corporate earnings indicators, with traditional gambling firms and hedge desks now fielding specialists to arbitrage contracts and price inefficiencies.

Taken together, these developments show that prediction markets no longer sit at the fringe. They are deepening ties with financial infrastructure, attracting professional capital, and provoking new laws, all while operating on an underlying mechanism that, at its core, is a form of wagering on uncertain futures.

The Zelensky Suit Was the Warning We Ignored

If the Maduro episode exposed the insider problem, the Zelensky suit market exposed something deeper.

In mid-2025, Polymarket hosted a market asking whether Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky would wear a suit before July. It attracted enormous volume. Hundreds of millions of dollars. It looked like a joke market, but it turned into a governance crisis.

Zelensky appeared in a black jacket and trousers designed by a major menswear designer. Media outlets called it a suit. Fashion experts called it a suit. Anyone with eyes could tell what had happened.

The oracle voted no.

Why? Because a small number of large token holders had massive financial exposure on the opposite outcome and enough voting power to force a resolution that suited them. The cost of corrupting the oracle was lower than the payout.

This was not a failure of decentralisation as a concept. It was a failure of incentives. The system behaved exactly as designed. Human governed oracles are only as honest as it is expensive to lie.

In this case, lying paid better.

Read: When is a Suit Not a Suit?🕴 - by Thejaswini M A

It is tempting to treat these incidents as edge cases. Growing pains. Temporary glitches on the path to a more perfect forecasting system. But I think that framing is wrong. These are not accidents. They are the natural outcome of combining three things: financial incentives, ambiguous language, and unresolved governance.

Prediction markets do not discover the truth. They arrive at a settlement.

What matters is not what most people believe, but what the system decides counts as resolution. That decision sits at the intersection of semantics, power, and money. And when large sums are involved, that intersection gets crowded fast.

Once you accept that, the controversies no longer appear surprising.

Regulation Did Not Come Out of Nowhere

The legislative response to the Maduro trade was predictable. A bill now moving through Congress would bar federal officials and staff from trading on political prediction markets when they possess material non-public information. Not radical. It is table stakes.

Equity markets figured this out decades ago. The idea that government officials should not profit from privileged access to state power is not controversial. Prediction markets are only discovering this now because they insisted on pretending they were something else.

I think we are overcomplicating this.

A prediction market is a place where people place wagers on outcomes that have not yet occurred. If the event breaks their way, they make money. If it does not, they lose it. Everything else we say about it comes after.

It does not become something else merely because the interface is cleaner or because the odds are expressed as probabilities. It does not become more serious because it runs on a blockchain or because economists find the data interesting.

What matters is the incentive. You are not being paid to be insightful. You are being paid to be right about what happens next.

What I do find unnecessary is the need to keep insisting that this activity is something more elevated. Calling it forecasting or information discovery does not change the risk you are taking or the reason you are taking it.

At some level, it feels like we are uncomfortable admitting that people simply want to bet on the future.

They do. And that is fine.

But we should stop pretending it is anything other than that.

Prediction markets are growing because people want to bet on narratives. On elections. On wars. On cultural moments. On reality itself. The demand is real and persistent.

Institutions are using them to hedge uncertainty. Retail traders are using them for conviction and entertainment. Media outlets are using them as signals. None of this depends on pretending the activity is something else.

In fact, the disguise is what creates friction.

When platforms claim a moral high ground as truth machines, every controversy feels existential. When a market resolves in a way that feels wrong, it becomes a philosophical crisis instead of what it actually is: a dispute over settlement in a high-risk betting product.

The expectations are misaligned because the story is dishonest.

I am not anti-prediction markets.

They are one of the more honest ways people express belief under uncertainty. They surface uncomfortable signals faster than polls. They will continue to grow. But we do ourselves a disservice by pretending they are something more virtuous than they are. They are not epistemology engines. They are financial instruments tied to future events. That distinction strengthens them. It allows for clearer regulation, clearer ethics, and clearer design.

Once you admit you are running a betting product, you stop being surprised when betting behaviour shows up.

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.