Wall Street Bought the Stadium

From $110B media deals to $9B prediction markets, sports has been financialsied.

Hello,

Earlier this week, Mr. Beast, the largest individual creator on the internet, acquired Step. a fintech company built to offer banking and investing products to teenagers. It’s a financial on-ramp designed to feel native to a generation that grew up on YouTube, TikTok, and online communities.

Now you might think it’s just another creator expanding into fintech. But no, the more interesting angle isn’t the acquisition, it’s what it represents. One of the most powerful distribution engines in the world was just plugged directly into a financial infrastructure! Attention is no longer just being monetized through ads and sponsorships, it’s being routed into financial products.

If you look closely over the past decade, the business of entertainment has changed. Today, Media rights are negotiated years in advance and valued like real assets. Prediction market platforms turn cultural events into tradable markets. Private equity firms allocate capital to sports franchises the same way they would to real businesses or software.

Interestingly, nowhere is this clearer than in sports.

Major leagues today derive the majority of their revenue from broadcast contracts rather than ticket sales. Franchise valuations have grown faster than underlying operating profits. Around every game now sits a web of sportsbooks, data providers, trading platforms, and capital pools that generate their own economic activity, often independent of the result on the field.

The entire industry is layered on top with a financial system that did not exist at this scale years ago.

In this piece, I want to explore how this shift happened, why sports became the testing ground, and how much of what we call “sports” today is actually finance layered on top.

Let’s dive in.

When Entertainment Became an Asset Class

For most of modern history, entertainment was a hit-driven business.

A film either worked at the box office or it didn’t. A tour either sold out or it didn’t. For sports teams, matchday revenue was the lifeblood. Everything depended on how many people showed up at the stadium, bought tickets, purchased beer, and filled seats week after week. Teams were regional institutions because distribution was regional. You supported your local team because it was the only one you and your community could realistically follow.

Then came televisions and changed that, but not for the reasons we assume. At first, sports were simply a way to sell TV sets. Manufacturers needed a compelling way to convince households that a TV was worth buying, and nothing could draw more collective attention than a live game. But once broadcasters saw the audience numbers, they realized live sports were also a uniquely valuable advertising inventory. Unlike scripted shows, they were consumed in real time. Viewers rarely skipped commercials during a championship game, and the uncertainty of the outcome kept people watching until the very end. For advertisers, this meant guaranteed attention at scale, something that very few other formats could offer.

As soon as television spread across households, sports moved from being local events to national broadcasts. Cable television actually played a major role in accelerating this transition. Sports channels were paid a fee for every cable subscriber, whether that household watched sports or not. That created reliable, recurring income for broadcasters. With steady subscription money and strong advertising demand, networks could afford to pay leagues much larger, long-term media rights deals. Over time, the real money shifted away from stadium ticket sales and toward broadcast contracts signed years in advance.

As distribution expanded beyond geography, the fan bases for these teams globalized, too. Today, it’s completely normal for someone in Mumbai to wake up at 3 a.m. to watch the NBA Finals live, or for a teenager in Seoul to own a Golden State Warriors jersey without ever having set foot in California.

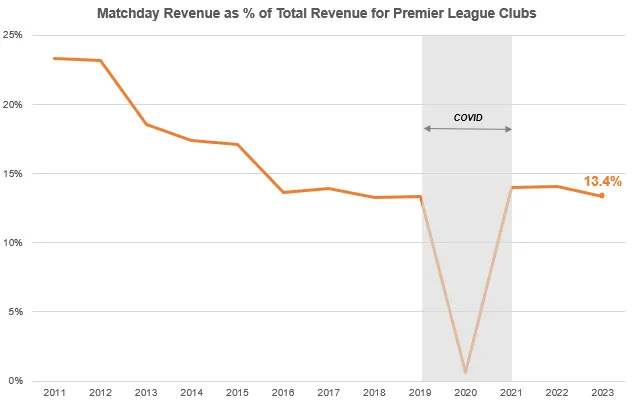

The data reflected the same, between 2011 and 2023, commercial revenue for Premier League clubs grew at an average annual rate of 9.3%, and broadcast revenue at 8.7%, while matchday revenue grew at just 2.9%. Over time, matchday income became a smaller share of total revenue. Media rights and sponsorships became the primary drivers of growth.

The next evolution was streaming.

When Netflix released House of Cards in 2013, it signaled that streaming was no longer just about delivering other people’s content more conveniently, it was now also about owning exclusive programming that viewers could not find anywhere else. Over time, every major platform adopted a similar delivery model and started providing “exclusive content”. As Benedict Evans put it, Netflix is not truly a technology company, its advantage comes from what it shows. People subscribe to specific shows, and they stay because those shows keep coming.

Among all types of programming, live sports stand out. They attract massive audiences who watch in real time, which makes them especially valuable for advertisers. When inflation rose and borrowing costs increased, streaming companies could no longer focus only on rapid subscriber growth; they needed profits. So they introduced lower-priced, ad-supported tiers to bring back advertising revenue alongside subscription fees, similar to the old cable model. And Live sports fit perfectly into this approach because they draw consistent, engaged viewership and allow platforms to charge higher advertising rates.

Although the decline of the cable bundle should have constrained broadcasters’ ability to pay ever-rising rights fees, the entry of Apple and Amazon into exclusive MLS and NFL deals expanded the buyer pool

The financialisation of Sports

Media rights had now become long-term contracts with steady revenue streams, so much so that sports teams themselves started to look like financiable assets.

For decades, sports teams were controlled only by wealthy individuals and families. Ownership was personal. It was about status, civic pride, or sometimes even obsession. Liquidity has always been low, and institutional investors stayed away because returns were uncertain and cash flows were uneven.

As broadcast revenue grew, it started attracting a lot of institutional investors to the industry. The NFL, which historically resisted private equity ownership, now allows firms suchas CVC, Carlyle, and Blackstone to acquire minority stakes in franchises. Redbird bought AC Milan in 2022 for €1.2bn, the highest figure ever paid for a football club outside the English Premier League. Dedicated sports funds were raised. Teams were no longer being bought solely by billionaires who loved the game. They were being bought by asset managers.

The returns explain why.

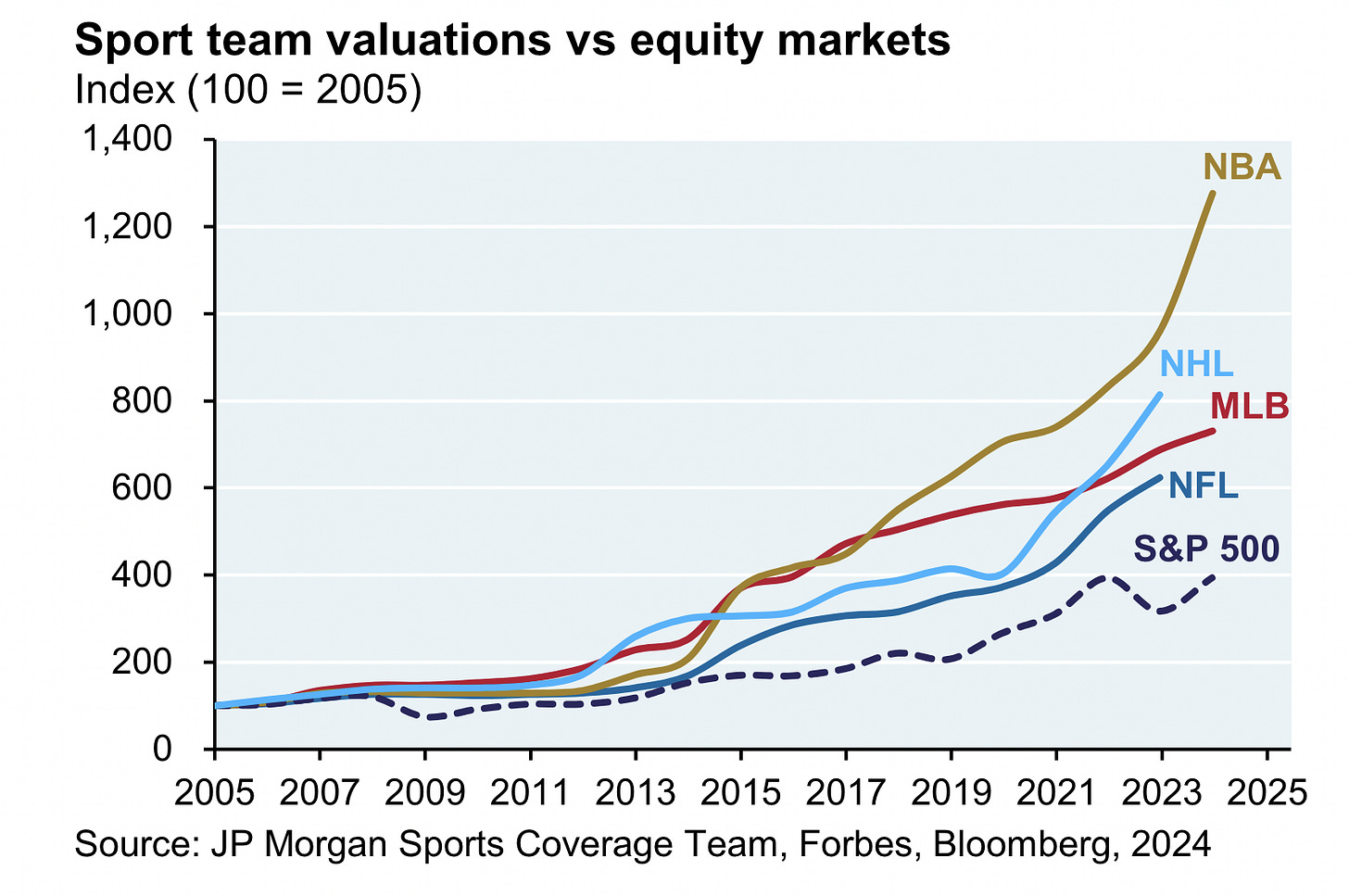

Teams have historically outperformed broader equity indices over long periods. Between 2010 and 2019, average NBA team valuations increased roughly 19% per year. MLB teams rose about 15% annually, NHL teams 13%, and NFL teams 12%. Those are asset-class returns.

Importantly, much of this appreciation was not driven by matchday profits. It was driven by expectations that media rights would continue to grow. Investors were basically underwriting future broadcast contracts.

Some firms even began investing directly in media rights streams rather than teams themselves. CVC invested in LaLiga’s media rights business. Sixth Street financed Barcelona’s future broadcast revenues. These deals separate the cash flow from the club and treat it as a financial product in its own right. If this was not it, scarcity amplified the effect. With only a limited 32 NFL teams and rising global demand, pricing power. Minority stakes began trading at control-premium valuations, sometimes with limited governance rights.

So much so that it changed the discussions around sports, it now centers around yield, appreciation, correlation to broader markets, and long-term structural growth in media consumption.

How much of sports is now finance?

Sportsteam ownership was just the beginning of financializaiton of sports. It is now embedded deeper into the games themselves.

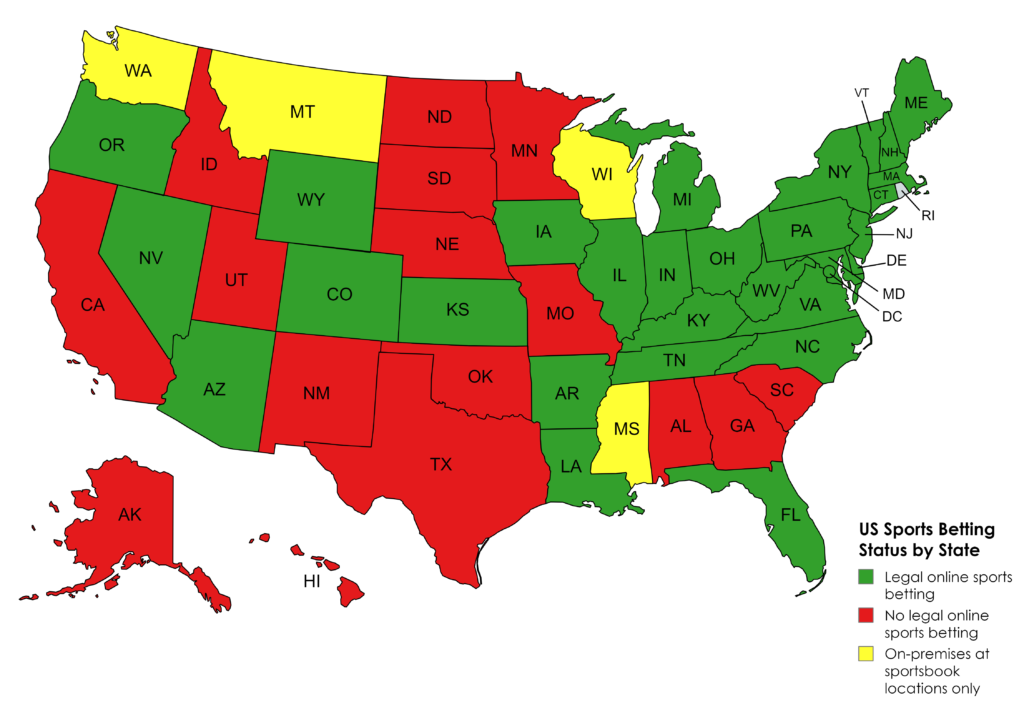

The most obvious example is sports betting. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned PASPA, allowing states to legalize sports wagering. Since then, 39 states and Washington, D.C., have introduced some form of legalized betting. What was once geographically limited to Las Vegas became nationally accessible through mobile apps.

Today, betting is no longer a side activity attached to sports. It is embedded into the broadcast itself. Sportsbooks buy prime advertising slots with Leagues selling official data feeds directly to these operators. Live odds update on the screen in real time. For many viewers, watching and wagering are now intertwined behaviors. It has created a flywheel where the game drives betting volume, and the betting volume drives viewership.

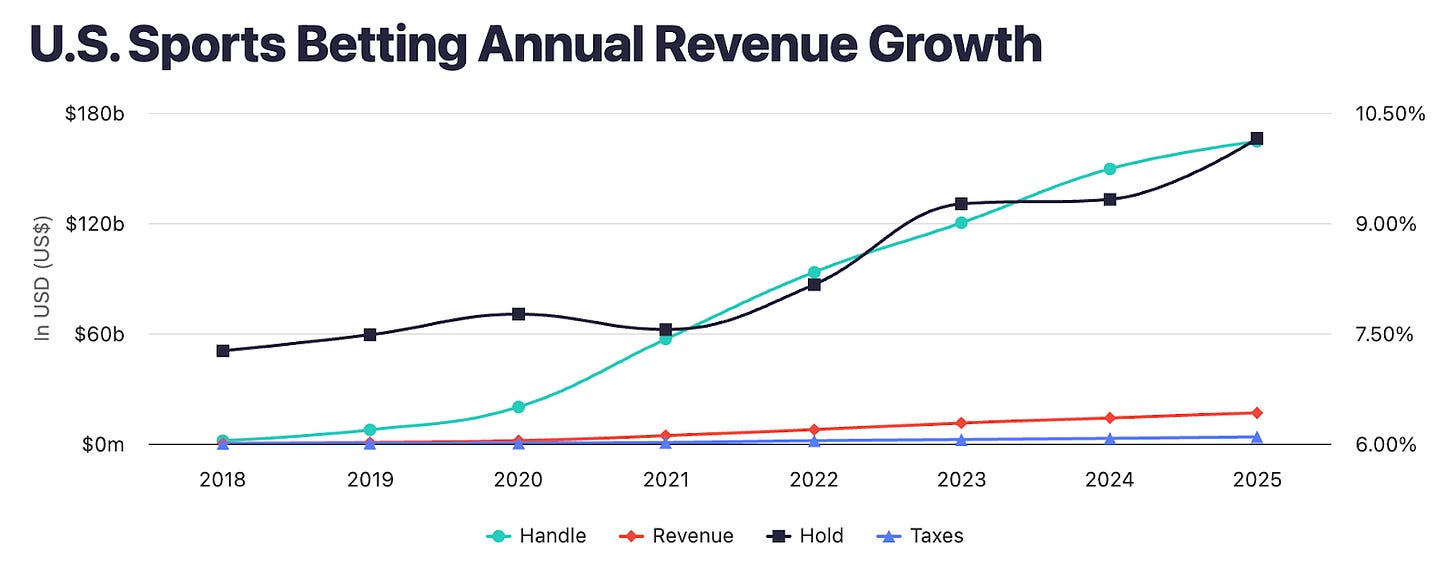

Companies like DraftKings sit at the center of that system. DraftKings generates roughly $5 billion in annual revenue from close to $100 billion in betting handle, capturing a small percentage of each wager as fees. With around 10 million users and a public market valuation near $16 billion, it represents the scaled version of modern sports betting layered onto digital distribution.

In 2025 alone, U.S. sports betting reached approximately $164 billion in annual handle, generating roughly $16–17 billion in operator revenue. In under seven years, wagering layered on top of games has grown into one of the largest recurring revenue streams attached to sports. More than 80% of that activity now happens on mobile, meaning the financial layer runs continuously alongside every game.

Prediction markets push this even further.

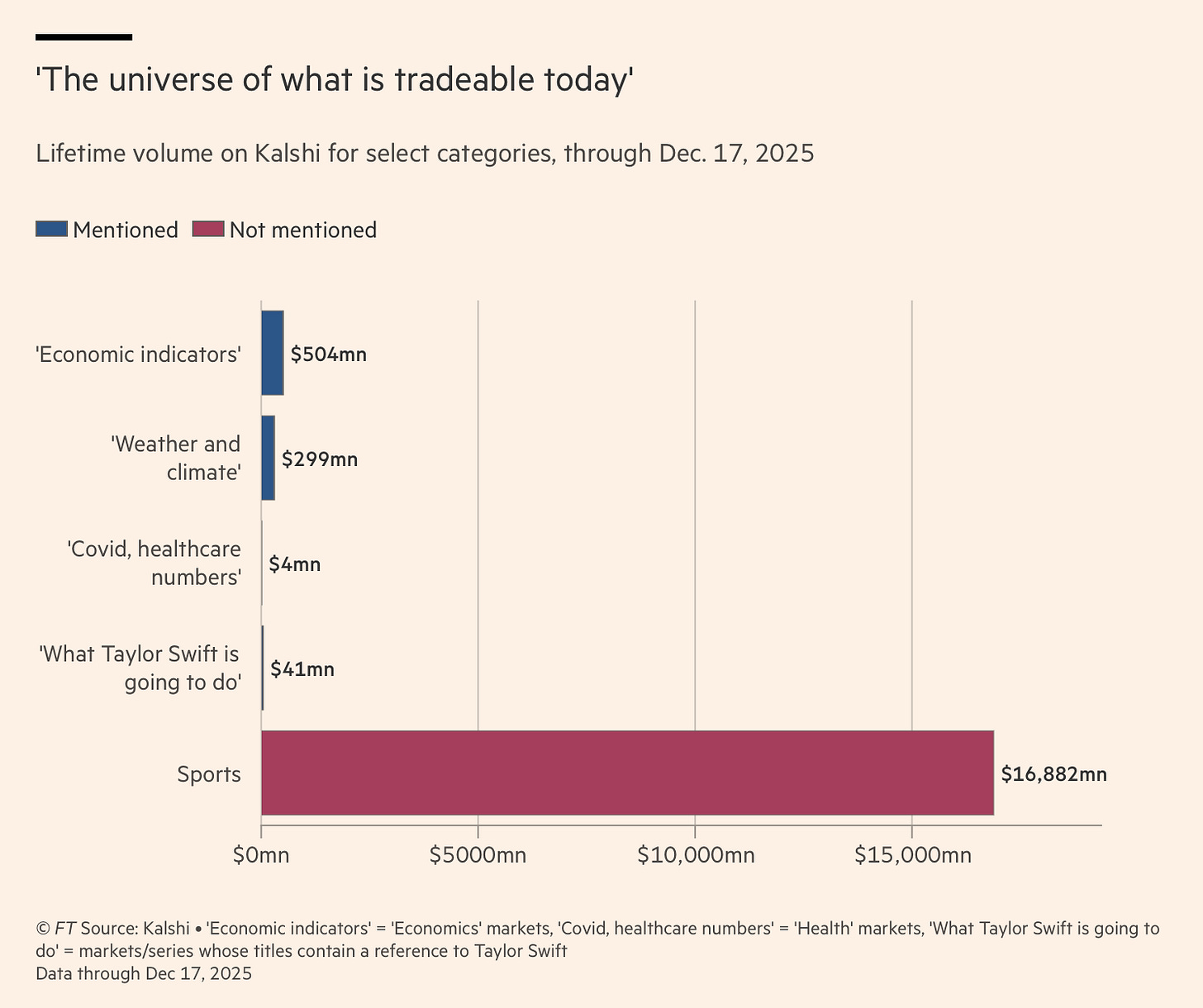

At peak periods, Kalshi’s activity has implied roughly $50–60 billion in annualized trading volume, with sports accounting for approximately 85–90% of total platform activity. During Super Bowl 2026 alone, Kalshi cleared roughly $1 billion in contracts tied to a single event, with weekly volumes exceeding $2 billion during major sports windows. Sports is not a side category for Kalshi. It is the liquidity engine.

Polymarket, while more diversified across politics and culture, still processes roughly $12–15 billion in annualized trading volume, with sports consistently representing one of its most stable and recurring verticals outside election cycles.

At peak annualized levels, Kalshi and Polymarket together process roughly $60–75 billion in trading volume. With global sports betting handle estimated near $1 trillion annually, prediction markets are already capturing approximately 5–6% of total wagering activity. That share has formed in just a few years. All without operating like traditional sportsbooks and without decades of regulatory and brand infrastructure behind them.

The key difference here lies in the model.

Traditional sportsbooks monetize wagers. They sit between fans and the outcome, take a spread, and scale with betting volume. Prediction markets aim to sit somewhere more foundational. They turn the event itself into a continuously traded instrument. A football match is no longer just a broadcast with ad slots; it becomes a stream of information that flows directly into a market. Every piece of information from injury reports, lineup announcements, referee decisions, weather conditions, and even crowd sentiment moves the price. The probability of an outcome updates in real time, through participants expressing conviction with their capital, and not through a bookmaker adjusting odds.

Those prices increasingly circulate beyond the platform. Prediction market probabilities are also increasingly referenced alongside news and traditional analysis. The number becomes a part of the narrative. In some cases, the market’s price influences public perception more than expert commentary. The “wisdom of crowds” metaphor becomes real.

There is also a psychological shift embedded here. Fantasy sports provided an early version of this dynamic. When fans had financial exposure to individual player performance, it had a direct impact on viewership and engagement. In India, fantasy cricket platforms helped push IPL engagement to record levels before regulatory restrictions disrupted the model.

Prediction markets simply amplify that effect. They enable events to trade as financial primitives, which also expands the scope beyond just sports to elections, the box office, and culture to become markets. Sports remain one of the largest categories because it generates constant, structured outcomes.

Entertainment + finance = funance

At this point, if you look at the shift, Broadcast contracts dominate revenue. Betting markets process tens of billions annually. Franchise valuations compound like growth assets. Prediction markets enable event trade in real time. The majority of economic energy surrounding sports now flows through financial layers built around the game rather than through the game itself.

What makes this interesting is that sports were simply the easiest place for this transformation to happen. It has frequency, global reach, and defined outcomes.

But it is now beginning to extend into the broader entertainment economy. Platforms that control massive audiences (Instagram/TikTok) are starting to attach financial products directly to those audiences. Streaming services, Netflix, for example, increasingly depend on live and high-engagement content to justify advertising tiers and protect subscription revenue. At the same time, markets now form around cultural events that were once purely informational. Elections, film releases, music chart rankings, product launches, and celebrity milestones are no longer just topics of discussion. They generate probabilities that are priced, traded, and circulated in real time.

What has changed is when and how entertainment generates value. For decades, entertainment generated money when people consumed it. Today, it generates money when people signal around it.

Humans are status-seeking monkeys. Social networks taught us that visibility and signal carry value. Financial markets just add a sharper edge to it. Instead of signaling with likes or reposts, people can now signal with positions. When attention can be converted into exposure, and exposure into a measurable outcome, you are no longer just a spectator. Sports showed us how that works at scale. The rest of the entertainment is beginning to follow.

That’s all for today. See you next weekend!

Until then, stay curious!

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.