Trustless Chickens P2 🐔

AI pigs, cloud farms, and the weird politics of letting models decide how life should be raised.

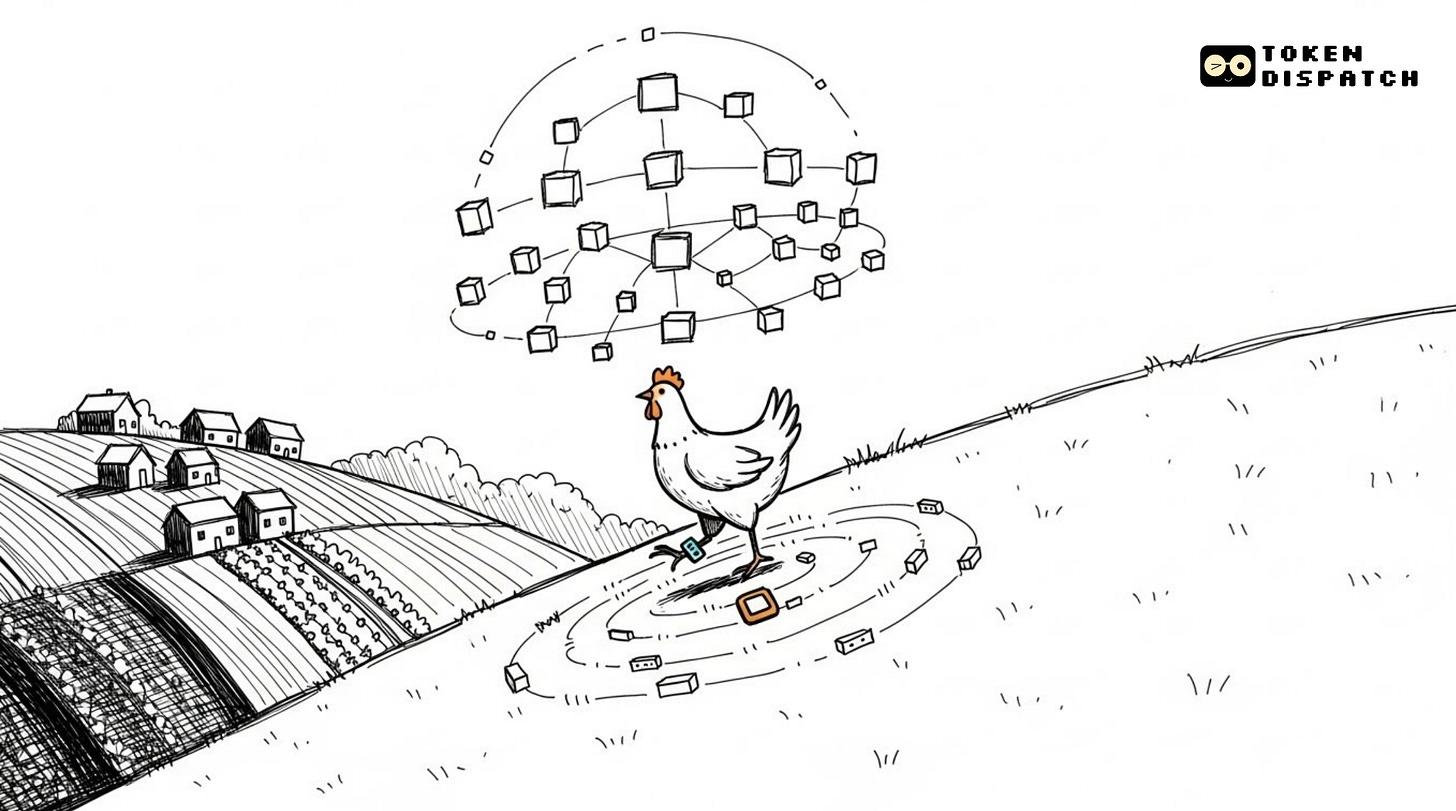

Last week, we left a chicken with an ankle monitor walking around a mountain in Guizhou, quietly generating data for people far away. This week, the animal is different, but the question remains the same: What happens when you treat life as something you can tune with a dashboard?

The book shifts from poultry to pigs, but really it shifts from “blockchain as prosthetic trust” to “AI as prosthetic decision making”. The chickens were already weird. The pigs are worse because pigs are where Chinese politics, global trade, climate, disease, venture capital, and cloud computing all intersect in one animal.

Read: Trustless Chickens 🐔

If the blockchain chicken was about paranoia, the AI pig is about optimisation. And underneath both is the same anxiety: things have spun so far out of control that we want software to put the world back into a shape we can tolerate.

Houdini Swap: Disappear Between Swaps

Most swaps today leave breadcrumbs everywhere, wallets linked, histories exposed, flows tracked. Houdini Swap fixes that.

It lets you swap crypto privately, breaking on-chain links between sender and receiver so your activity stays yours. No accounts, no KYC, no unnecessary exposure.

Cross-chain swaps with built-in privacy

No wallet tracking or transaction history leaks

Simple interface, serious anonymity

Designed for users who value freedom, not surveillance

If privacy matters to you in crypto, this is worth a look.

In Guangzhou, Wang starts with something very ordinary. Late autumn, laundry on balconies, slabs of pork tied with string, curing into lap yuk. Preserved meat dangles next to shirts and bedsheets. There is a whole world of bacteria, wind, and tradition working on those slabs, long before any sensor does.

At the same time, they are waking up at 5 a.m. to read Pig Progress, a pork industry publication, following African swine fever as it creeps toward China. A disease with nearly-perfect fatality, hitting the world’s largest pork producer. A slow motion disaster for farmers, yes, but also for the Chinese state, which knows exactly what rising food prices can do to political stability.

Pork in China is not just “meat”. It is history, medicine, national identity, calories, and social peace. The state literally keeps a strategic pork reserve. There is an entire architecture of control built around keeping the average person’s pork bowl affordable.

That also means there is an entire architecture of risk. Industrial pig farms in China, American companies like Smithfield, and Brazilian soy fields carved out of the rainforest. Pigs as nodes in a global system of feed and finance, not just animals on a hillside. When African swine fever hits that system, it does not care about anyone’s optimisation spreadsheet.

If you are an anxious tech billionaire looking at this mess, there is a familiar response. The system is complicated and fragile. Humans are messy. Let us build calmer, cleaner, fully controlled pigs.

Enter Ding Lei from NetEase. One day, he looks at a hot pot and decides the pig blood might be fake. In that moment, his attention flips from games to pork. He builds a farm under a new division, Weiyang, with the precision of an electronics factory and the aesthetics of a spa.

The pigs get carefully calibrated feed, carefully designed exercise, and carefully selected soothing music. The point is not their comfort as such. The point is to avoid stress because stress produces bad meat. There is an industry term for it, “DFD” meat, dark and firm and dry, a defect in the eyes of processors.

You can see the logic. If bad inputs produce bad outputs, fix the inputs. Standardise the pigs. Standardise their environment. Clip away tails that cause trouble in crowded conditions. Treat DNA like code and the farm like a factory line.

What Wang does, sitting with this, is quietly poke the premise. Can you actually “optimise life?” What would that even mean? Optimise for what? For feed conversion. For taste. For a spreadsheet target. For a risk officer’s sleep. How would you ever know if you picked the right one?

Optimisation assumes you have identified all relevant variables and that nothing unexpected will arise. African swine fever is the universe’s way of reminding everyone that this is not how biology, politics or weather actually work.

The chapter then pivots to the question every management consultant eventually asks about farmers. If humans are boundedly rational, subject to limited time and information, why not let models take over. If you can feed an AI every weather pattern, every historical yield curve, and every disease pattern, every market signal, surely it will make better decisions than someone standing in a muddy field.

Alibaba leans all the way into this fantasy with ET Agricultural Brain. It sounds like a Marvel villain and a PowerPoint object at the same time. An AI stack that promises to transform agriculture, to help create China’s “pork miracle”.

Wang visits Alibaba Cloud’s campus in Cloud Town. It looks exactly the way you think a cloud campus looks. Grey carpets, fridges with bottled drinks, a corporate “Cloud Computing Museum” to narrate the triumphs of infrastructure. The idea is familiar from Amazon and every other big platform. We built this capacity to sell products online, now we rent the leftover servers to everyone else.

Within that infrastructure, ET Agricultural Brain is pitched as a general purpose mind for fields and barns. It can determine when to plant, when to harvest for optimal sweetness, how to route cold chain logistics, and how to adjust feed. It plugs into other Alibaba products such as ET Logistics Brain and ET City Brain, a set of modular systems that promise to govern traffic, warehouses, pigs, melons, or whatever you have.

On the slide it all looks clean. The AI is the brain with perfect memory, farmers are reduced to hands and sensors, just another line in the cost column.

Crypto often talks about “automation” too.

We now have market makers that run all day, liquidation bots that never stop, rebalancing vaults that remember everything, and agents that track every little basis trade. The nice story we tell is that this automation is just taking the boring work away from humans. The less flattering version is that we are gradually redefining “being human” as “anything not worth automating yet.”

Wang connects agricultural AI to this larger myth of the automated future. The myth always comes with a built-in hierarchy of value. Rational, efficient decision-making is elevated. Anything that appears to be emotion, intuition, or embodied knowledge is classified as noise.

I am not romantic about smallholder farming. It is hard work and often exploited work. But there is something deeply off about pretending that the only thing worth saving from a farmer is their willingness to follow prompts in an app.

In the AI pig story, the animals are being optimised, but so are the humans around them. What counts as a “good farmer” becomes “someone whose decisions trace the model’s recommendations.” Deviate from the prediction, and you are not being innovative, you are being irrational.

Once you see that, it is hard not to see similar games in crypto. What counts as a “good user” is someone who behaves as the protocol expects. What counts as a “good community” is one that passes governance proposals in the direction the core team wanted anyway.

There is this quiet split in the chapter between lap yuk and the AI pig. The cured pork hanging off apartment balconies depends on the city itself, on the air, the weather, and the neighbours. It is part of an ecosystem. The AI pig, raised in a sealed, sensor-filled barn, is part of a pipeline. One trusts place and habit. The other trusts data and models.

African swine fever disrupts that ecosystem by undermining the assumptions that made industrial farms seem safe. ET Agricultural Brain steps in with a promise that this time, with enough sensors and enough compute, we can finally eliminate uncertainty.

You can draw a straight line between that promise and a lot of blockchain pitches. Decentralised exchanges that will never go down. Self-executing contracts that will never be misinterpreted. Stablecoins that will never break. As long as you can measure everything, you can manage everything.

But as the pig story shows, the world is not just a set of measurable parameters. It is also a disease, a panic, a policy, a culture, and the one farmer who refuses to do what the model says because the clouds look wrong today.

What Wang is really pushing us to admit is that optimisation is not neutral. It reflects someone’s priorities. Whose volatility are we smoothing? Whose risk are we minimising? Whose costs are we willing to externalise to get a tidy dashboard?

Something breaks trust on a massive scale. In food, it is melamine, scandals, and ASF. In finance, it is fraud, crises, and opaque leverage. We respond not by rebuilding trust but by layering additional computation on top. More scanners. More proofs. More models. More dashboards.

In that process, the life underneath the system gets flattened. The chicken becomes a QR code. The pig becomes a data point for the ET Agricultural Brain. The farmer becomes a bounded-rational nuisance that you can eventually circumvent.

Wang does not offer an easy alternative. They are not saying “throw out the machines and go back to an imagined pure countryside.” What they are doing, page by page, is forcing you to sit with the humans who are supposed to be “helped” by these systems and ask whether ‘’help’’ is really the right word.

Next week, in part three, I want to follow the book into how all this infrastructure actually lands in people’s daily lives beyond farms – in factories, in Taobao villages, and in global supply chains. But for now, I am staying with this image: AI raising pigs, cloud platforms managing fields, investors talking about “pork miracles,” while spores in the Guangzhou wind quietly cure meat on balconies.

You can optimise a lot of things with models. You can instrument an astonishing amount of life with sensors, chains, and brains in the cloud. What you cannot do, at least not yet, is teach a model what matters about a pig to someone who is not on the cap table.

That’s where I’m going to park it for this chapter.

Next week we’ll do part three. Until then, stay curious.

Token Dispatch is a daily crypto newsletter handpicked and crafted with love by human bots. If you want to reach out to 200,000+ subscriber community of the Token Dispatch, you can explore the partnership opportunities with us 🙌

📩 Fill out this form to submit your details and book a meeting with us directly.

Disclaimer: This newsletter contains analysis and opinions of the author. Content is for informational purposes only, not financial advice. Trading crypto involves substantial risk - your capital is at risk. Do your own research.